A stray New Haven RR FL9 didn’t add up when the commuter locomotive encountered a Seaboard System equipment detector.

When I entered engine service on the Seaboard Coast Line in 1979, the railroad was replacing many of its first generation locomotives, mostly aging Alcos and Electro-Motive Division road switchers. These locomotives had been ideally suited for SCL’s local freight business, which required enough power to stay out of the main line big boys’ way, while being light and agile enough to navigate light rail branch lines and sidings.

Finding nothing on the market to fill the void, SCL began a rebuilding program at its Utica Shops, in Tampa, upgrading structurally sound GP7s and GP9s into class GP16s. Everything from nuts and bolts to electrical systems was to be replaced — yielding a practically new unit. The GP16 was a placeholder until something better was available. The GP16 could “pick up and go,” and with their chopped short hood and as-intended road switcher configuration, they provided excellent visibility to safely handle switching chores. Until I opted for direct employment by Amtrak in 1986, I spent a lot of time on local freights, switchers, and work trains, often running GP16s.

A second vehicular crossing of the wide expanse of water, know as Hampton Roads, was then under construction and was named for the first two ironclad warships to confront each other at that very location during the American Civil War. Delivering building materials for the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge Tunnel resulted in three round trips weekly, hauling stone from a quarry near Emporia, Va., to the huge natural harbor surrounded by Portsmouth, Norfolk, and Newport News. We usually left Richmond’s Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac’s Acca Yard with a pair of GP38-2s, or a trio of GP16s, and a caboose, for a straight shot down the former Atlantic Coast Line main, paralleling I-95, to pick up the rock. Occasionally, we’d do a little local work.

One dark night, we coupled up to a real stranger in our neck of the woods — a Metro North EMD FL9 hybrid diesel and third-rail electric, en route Norfolk, Va., for rebuilding. A railfan, I delighted in explaining the oddball engine’s history to my crew. They weren’t impressed. It was just another locomotive to them. All SCL defect detectors were audible, broadcasting the condition of a train and its axle count on the railroad’s radio frequency.

After we uneventfully passed a third detector, the local trainmaster radioed us.

“Rock Train,” he said, “that’s the third time you’ve gotten an odd-numbered axle count. That’s an error. When a defect detector transmits a false report, you’re required to stop and inspect your train.”

“False report?” I asked.

“I’m not aware of any cars with an odd number of axles,” he sneered. “Your crew would appear to be in violation of the rules.”

“Sir, we have a dead-in-tow engine with five axles — two in front, and three on the rear, so the axle count is correct.”

“You are pulling my leg, aren’t you, Mr. Riddell?” he asked, a little hesitantly.

“No, sir,” I said. “Come take a look.”

“No, that won’t be necessary. Carry on.”

Very interesting story. This is the first I had heard of an FL-9 being rebuilt in Norfolk, as most were done by Morrison-Knudsen.

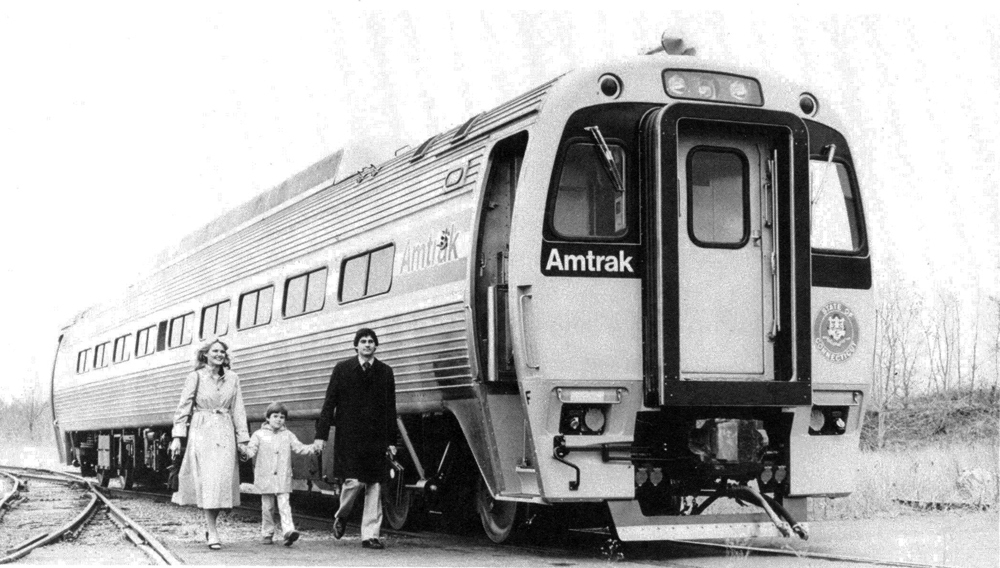

Remember that the dual-power concept pioneered by the EMD FL9 has been continued by the GE Genesis P32AC-DM and EMD DM30AC, both which remain on Amtrak, Metro-North and the Long Island Rail Road.

Dr. Güntürk Üstün

The lovely Seaboard System road switcher GP16 No. 4978 (an ex-GP7) looks proud and joyous from the railroader author’s valued collection.

Dr. Güntürk Üstün

Vincent R Saunders,

I consulted Kalmbach’s 1973 “Second Diesel Spotter’s Guide,” by Jerry Pinkepank, (which by the way, sold for an astounding $6.75) which didn’t give a specific reason for the FL9 designation. However I believe I was once told, or read, that since the locomotives, which were built in 1956-57 and 1960, exclusively for the former New Haven Railroad, were lengthier than the FP7 or FP9, thus that the “L” was intended to stand for “longer lengthened.” The 1956-57 FL9 got its 1750 HP from a 567C prime mover, but the 1960 order came with 50 HP more, derived from a 567D1. I’ll keep looking. I’m just as curious as you. Possibly another reader, more familiar with the New Haven, can help us out. Thanks. Doug

Thanks, Charles and John. I’d never given much thought to coming out of Grand Central Station, only to discover that the diesel prime mover wouldn’t turn over. It didn’t happen too often, but when it did happen (with any diesel on any railroad), it was always at the wrong time and in the most inconvenient place. I usually said a little prayer when I pushed the starter button and gripped the lay shaft on a unit that had been shut down for any length of time. The strain on the batteries meant that you didn’t get too many shots at it.

Doug, Charles or John, What did the FL in the model designation stand for? Most of us know that “GP” was for General Purpose, “SD ” was for Special Duty, “F”was for Fourteen Hundred (HP) and “E” was for Eighteen Hundred (HP) on the EMD road units. But FL? Did it have anything to do with the fact that the pickup shoes for third rail contact was of the “Long” Island Railroad type? That is the closest thing I could find that made any sense. If you know of something let us all know…

When FL9s were restricted to the two or three NH tracks on the eastern side of GCT’s upper level, it was not uncommon to see a dark haze of Diesel exhaust hovering over those tracks. This was particularly true in winter when Diesel engines were reluctant to restart after being shut down for several hours.

Another great story thanks Doug!