So says Rick Paterson, a one-time Australian railroader who is an analyst for Loop Capital Markets.

“A lot of railroads are really very, very fragile,” Paterson says. “And a Hurricane Harvey or a polar vortex are basically a gut punch to these systems.”

The problem is that Class I railroads, mindful of Wall Street’s focus on the operating ratio, try to perfectly match crew and power resources with their current traffic levels, Paterson says. And that leaves railroads with no margin for error.

Paterson, who shared his analysis at the North American Rail Shippers association annual meeting last week, lumps rail service into three categories: bad, good, and truck-like.

Bad service is meltdown mode, when operating metrics fall 10% or more below average and take six to 15 months to recover. Good service is when freight generally arrives on the right day but is neither time-definite nor dependable. Truck-like is “rail utopia,” with day- and time-definite reliability and predictability.

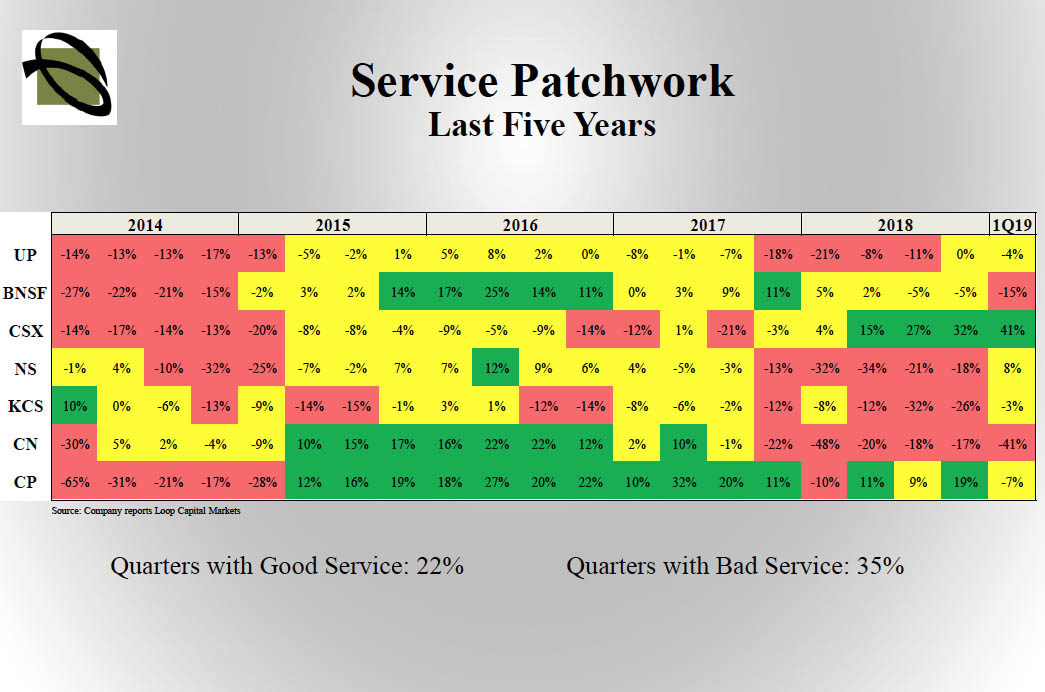

Paterson took each Class I railroad’s average train speed and terminal dwell figures and combined them into a single service metric. Then he plotted this service metric against each railroad’s average since 2010.

His conclusion for the industry as a whole? Over the past five years, only 22% of quarters had good service, while 35% of quarters had poor service. The remaining quarters were a hodge-podge, with no clear trend.

Paterson walked through the metrics for each of the Class I railroads.

“CSX is arguably the best-running railroad in North America right now,” Paterson says, noting that the CSX service composite is currently 41% higher than its historic average.

He noted how CSX stumbled through the first so-called polar vortex in the winter of 2013-14 and then again when CEO E. Hunter Harrison made rapid operational changes amid the shift to Precision Scheduled Railroading in the summer of 2017.

“Hunter Harrison cuts the merchandise network over to PSR without apparently telling anybody, including his own operating people,” Paterson says. “But as usual, he was right and everything worked out and all was forgiven.”

PSR railroads are more resilient and have provided the most consistent service, Paterson says, singling out Canadian Pacific as the steadiest performer.

Service suffered at all of the Class I railroads during the frigid winter of 2013-14, Paterson notes, but since then the non-PSR railroads experienced deeper, more prolonged, and more frequent service problems.

A PSR exception was Canadian National, which could not handle a 10% surge in volume in late 2017 and has not been the same since. Paterson says he’s willing to give CN a pass since no railroad ever anticipates such a large spike in volume.

Paterson contends that railroads should prepare for more unpredictable weather events. Climate change is likely to produce more extreme flooding, cold snaps, and wildfires that can wreak havoc on operations, he notes.

It’s good news that six of the seven Class I railroads are adopting PSR, Paterson says. After a pair of hurricanes last year, for example, CSX bounced back quickly while NS velocity sank to its lowest levels since the meltdown after the Conrail split two decades ago.

Railroads can maintain an adequate buffer supply of crews and power relatively inexpensively, Paterson says, which would help maintain service levels.

Sooner or later railroads’ pursuit of lower operating ratios will come to an end because they won’t be able to justify above-inflation rate increases, Paterson says. When that day comes, railroads will have no choice but to seek more robust volume growth, which will require more power and crews.

Ultimately, shippers can encourage railroads to provide more consistent service, Paterson says.

First, they can do a better job communicating expected volumes to railroads. Second, they can encourage railroads to reduce locomotive risk by supporting multiple manufacturers. Third, they can help railroads reduce crew risk by supporting an eventual move toward partial autonomous operations.

Well, at least the railroads and commercial aviation now have something in common.

The problem isn’t PSR per-se, it that the RRs really don’t know how much “cushion” they have with their resources. The budget process and OR goal dominate. They could model things and have a good idea of how resilient/fragile their operations are, but they are busy doing other things – and the OR push means there are fewer folk on staff to analyze these things. It’s still “here’s the budget – can you do it? (BTW, the right answer is “yes”)”

The crew problem has been made worse by two things. The hours of service rules that require mandatory days off and the agreements that guarantee a number of starts per month. The first reduces the “cushion” of the existing pools, the second provides great pressure to trim rosters when things are good. PSR is irrelevant to this process, at best, and likely makes it a bit worse. A smoother, more steady state by day of week plane means crew pools can be trimmed a bit more since you don’t need that extra turn or two to cover a day of week bulge.

This is not to say that there aren’t folk on the inside who know that this is going on and it’s a problem. It’s just there is only so much work that can be done and leadership’s priorities are elsewhere.

DUH! We all knew that already.

Railroads cannot figure out “opportunity costs” in their analysis. That is the money lost when service deteriorates and shippers move away from rails. What makes the analysis hard is that there is nothing to count but wild guesses of what might have been. Businesses all over understand that you must have extra capacity to serve surges (Walmart has more that one box of granola on the shelf; even though that is all that may sell today.) Railroads don’t have that outlook. They run right at full capacity and cannot flex when weather or demand changes. Guess management missed that day at MBA school.

Overlay the volume graph over this and you will likely see that it’s not just reserve for weather and events but also a capacity ceiling to expand above additional funding is required. Other than CN (restoring) lone haul and terminal capacity in western Canada and BNSF debottlenecking the southern transcon snd to a lesser extent the northern one, who else is truly expanding capacity?

Jf Turcotte, prove to the world how he railroads are going out of business! There so much more out there than what you are seeing. If a business of any form cannot keep a monetary reserve for investment of any style/form, then why be in business in the first place? That’s what ultimately did the Penn-Central in, coupled with horrendous service. PC even did a video on why they “needed” government funds to attempt to stay in business.

PSR is just one of many tools for service. With anything new, there bugs that have to be worked out and kinks with interchange operations have to find ways to find fluidity with each other. There cannot be any simple “flip the switch and you’re back to pre-PSR days” regarding service troubles. Yes, the railroads have problems, but also customers should be held accountable if they don’t live up to the service contracts and get cars unloaded/loaded in a timely manner. (BTW, trucking has a similar thing; it’s called Detention.). But if a customer feels pinched by demurrage fees, then they have every right to raise Caine about it.

If UP is not able to generate enough cash flow to pay off the bonds and invest in its infrastructure, maybe it should ask itself if it is not returning too much of it to shareholders in the form of dividends.

As it is currently implemented, PSR is just a just another word for a sophisticated going-out-of-business strategy.

It is just as easy for most non-bulk shippers to work with truckers vs the foibles of the railroad industry. There is almost a revolt going on with the PSR railroads and it customers over demurrage fees and failures of delivery of rail cars in a timely manner. I am for efficiency too, but I think overall the railroads have and are cutting into the bone and with that have little operational resiliency anymore. Not good.

There’s really only ONE solution: More Precision in the Precision Schedules. Until things are precise, how can anybody expect things to improve? Give-em’ a few more years…

For those who may be interested, Loop Capital is just like any other investment firm that has existed before. Yes, to me this chart is interesting, but it doesn’t really tell me much else beyond what is already known regarding service troubles. Each railroad has its problems with service kinks, but if all that is looked at is the small picture like the provided data chart, then you tend to miss other things that may be causing problems.

Union Pacific, for one thing, has had to work with numerous changes in the railroad scene (outside of the usual weather snafu’s) that have come on at such a rapid pace that they have been slow in responding accordingly to them. However, the single lesser know problem that UP is facing regards upcoming bonds. Over the next 10 years, UP has to face at least five billion dollars of bonds at an average rate of 4.5% to payoff. Beyond that, they are staring at the prospect of 10 to 15 billion dollars of bond payoffs over the course of the next 20 years. All the while, UP has to invest in its infrastructure and service provision (even if it is not the best up front.)

Now, as I have said before, it is nice to see which railroads have performed better according to this chart, but always remember, folks, is that a picture is worth beyond 1,000 words.

Bill; I imagine this gentleman was “preaching to the choir” at a NARS meeting. Any shipper who has been in the business for a minimum of ten years has already experienced several of these cycles whereby the railroads cut too much; business rebounds or there is a period of bad weather; the railroad seizes up; then management goes on another hiring spree for TYE personnel.

UP and NS went through the hiring cycle last year and are now in the process of furloughing all the new people they recruited, hired and trained at God only knows how much expense.

I’m reminded again of the supposed definition of insanity – doing the same thing the same way every time but; always expecting a different result.

I completely agree! I’ve been shouting this for quite a while. Glad to have more voices joining the chorus.

An anomaly that bottoms out a resource like a crew pool can throw operations in the ditch. It takes more resources than you need for steady state to get operations out of the ditch.

There is still too little science and too much budget pressure applied to “right sizing” resources. This has been made even worse with the current PSR/OR rage.