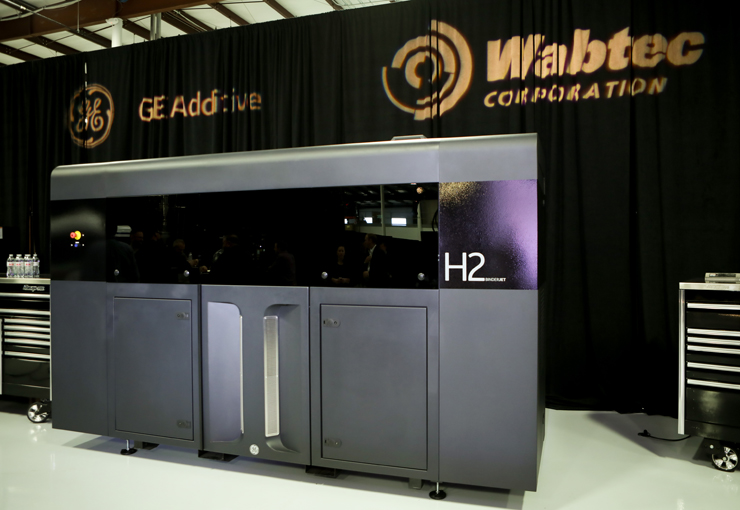

GROVE CITY, Pa. — As diesel locomotive engines are being manufactured outside its doors, a quiet lab, no bigger than a small store, in a corner of the Wabtec factory in Grove City is magically creating industrial components from powdered stainless steel using lasers. Asked if this is leading-edge technology, the lab’s chief, Jennifer Coyne, replies, “No … it’s bleeding-edge technology.”

Commonly known as 3D printing, which in its simplest form can be done at home with printers costing just a few hundred dollars, industrial-scale additive manufacturing – so called because items are built one microthin layer at a time – has to date largely been confined to the aviation, aerospace, automotive, and health care industries.

Wabtec, which acquired the Grove City facility from its merger with GE Transportation, is bringing this advanced technology to the railroad industry, where it has the potential to replace casting and forging for some industrial components.

Recently, the lab helped get a customer’s prime mover, in for overhaul, back in service quickly when needed cast pieces weren’t delivered from the supplier on time. “We were able to print them, so they can build the engine and not miss the date,” says Coyne.

She has worked on railroad technology for 12 years, mostly tackling things like adhesion systems for locomotives. Two years ago, Coyne took on the role of additive manufacturing leader. “It’s really neat to bring new technology into a relatively old industry,” she says.

Trains News Wire was given an exclusive, first look at that technology during a tour of the lab, which is still coming together, with three additional machines due in December.

The high-ceilinged, white-walled space is clean and quiet, with test parts and prototype components scattered along small shelves. In one corner stands a tall gray cabinet that contains a curing oven. A glass booth, about the size of a large walk-in closet, houses an industrial-level 3D printer for classic polymer-based printing.

Wabtec is now pioneering two sophisticated metal-printing processes.

In the first, a direct metal laser melting machine deposits a fine metal powder layer by layer, building up a three-dimensional object, often requiring thousands of passes. Instructions are sent from a design computer. It’s a slow process, says Coyne, but works well for prototyping, low-volume output or highly complex parts. “In this process, we get really good first-pass yield,” she explains. Finishing requires the removal of excess powder (which can be reused), cutting the component from the build plate, removing any support structures, and final machining.

At times, they’ll come across an out-of-production part that needs replacing. Using a 3D scanner, a laser precisely measures the existing component and the resulting computer model is used to recreate the part.

That can help keep older locomotives on the road, saving replacement costs. 3D printing has also demonstrated its ability to keep vintage aircraft flying and could find applications in the restoration of historic railroad equipment.

A second process breaking new ground is direct metal-jet binding. Instead of using lasers to build up each layer, an inkjet printhead deposits tiny drops of a binding agent onto a bed of metal powder, essentially gluing the object together.

“We’re one of just a few beta customers that own this machine and one of the first develop to it out,” Coyne reveals.

The piece, called a green part, is then sent to the curing oven to evaporate away the glue. From there, it moves to a high-temperature sintering oven. At 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit, just below the melting point of stainless steel, the metal becomes fused to its final form.

What’s left, after some machining of critical surfaces, is a part that emulates a traditionally cast component. Wabtec sees this process as suitable for volume production in the railroad industry.

“It may take you a few tries to get it right because you’re going to have some shrinkage, some distortion,” Coyne explains. “But when you get that process right, it’s just very efficient.”

The lab will have five production parts ready for additive manufacturing by the end of this year, with a goal of 250 by 2025.

Manufacturing with this process enables greater design freedom. More complex component geometries, including internal channels and passages that can’t be made with traditional machining, become possible, delivering cost savings and higher quality. “Right now, we’re working on a heat exchanger for a locomotive that is typically up to a thousand parts,” says Coyne. “And we’ll print it in one.”

Coyne points to another breakthrough, this for the hybrid battery-electric locomotive Wabtec is building in Erie, Pa., for BNSF [see “Wabtec has high hopes for battery-electric road unit,” Trains News Wire, Sept. 24, 2019]. Argon gas is used in the ultrasonic welding process that ties together the 20,000 lithium-ion batteries in the locomotive.

“We didn’t have a good way to control the gas flow to get a high-quality weld,” Coyne tells News Wire. An engineer on her team worked with the manufacturing engineer for the locomotive project and within just a few weeks, they developed, printed and tested 10 different designs to find the best one. “They created a patented argon gas nozzle that directs the flow more precisely.”

And it’s not just industrial tools or engine components: the power electronics on modern locomotives generate a good deal of heat. Wabtec is finding ways to design better heat sinks using additive manufacturing.

As with all emerging technologies, there are challenges and limitations. Cost can be one, especially for one-off or small-volume printing. Another is the lack of available raw metal powders to work with. “There’s a lot of immaturity in the market, and that limits the materials that are available,” Coyne says. The needs of heavy industry, such as low alloy steel, aren’t being served yet.

Asked about the biggest challenge in reaching the company’s ambitious goals, Coyne gave a surprising answer: the expertise on her team is ahead of the technology itself. Right now, the process is largely hands-on, but will become more automated as it develops. “We just have to have the maturity of the technology catch up,” she says.

And when it does, it will allow Wabtec engineers to increase the speed at which components can be developed, prototyped, and tested before production. Improved designs promise railroad customers greater locomotive fuel efficiency, improved emissions, more reliability and better performance.

Although holding back details that she can’t yet talk about, Coyne says, “In our pipeline we’ve got some really big, game-changing technology when it comes to performance improvement.”

Her conviction is echoed by Wabtec’s chief technology officer, Dominique Malenfant, who tells News Wire, “Additive is one of the most promising technologies to change the way we design a locomotive and gain performance. It’s going to be a transformative technology.”

Charles, they sold the business because they needed the money to try to save the business–still a work in process.They no longer have the resources (money un allocated) to wait out cyclical kinds of business like loco building.

As soon as I saw this article, I knew the technology came from GE. Still wondering why GE sold the business, great to see Wabtec taking advantage of the acquisition!

One could foresee this technology providing an invaluable resource for the restoration of heritage steam and diesel motive power where duplicatable parts and blueprints are available.

SpaceX uses the largest printer of this type made today to print fuel tanks. It’s amazing technology.