Keith Fender

BERLIN — In Germany. where the world’s first hydrogen powered train entered service in 2018, the new propulsion technology has not resulted in large contracts for new trains, although some have been ordered.

Almost every European country has signed up to remove diesel-powered trains by 2050 to lower future carbon emissions. Some are aiming to do this much quicker, using either battery or hydrogen power where additional electrification is too expensive.

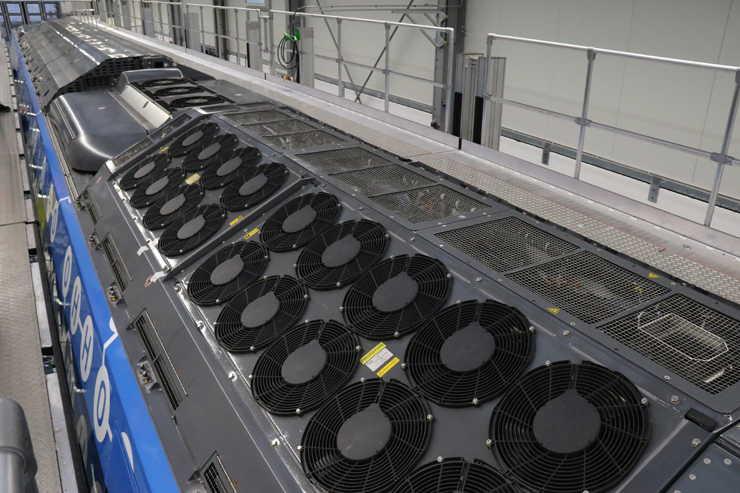

French-based Alstom developed the iLINT hydrogen powered train first used in Germany [see “Hydrogen-powered passenger trains enter service in Germany,” Trains News Wire, Sept. 18, 2018], and have sold 41 units (82 cars) to two German commuter rail operators, although few are yet in service. Another contract is planned near Berlin as of 2023. The iLINT and other hydrogen-powered trains use hydrogen fuel cells to create power to accelerate the train, but the train also has a large battery pack which is charged by excess power from the fuel cells and by regenerative electrical braking as the train slows. Alstom uses fuel cell technology supplied by the Hydrogenics subsidiary of Cummins.

The new train type that is outselling hydrogen — by more than 5 to 1 on the basis of future mileage contracted to each type in Germany — are simpler battery-equipped EMUs. Multiple European manufacturers have developed these designs, in some cases selling them straight off the design desk without prototypes. Siemens, Stadler. and Bombardier have all built demonstrator trains and Siemens, Alstom, and Stadler have won substantial orders for 86 trains (183 cars) between them in Germany alone. More battery trains have been ordered in other countries.

Battery-powered trains are not a new idea; they existed in the 19th century, but in the past used heavy lead batteries that were not very powerful or long lasting. Modern battery technology is different; billions of dollars have been spent developing lightweight, long-lasting powerful batteries, with automotive companies leading this effort. Battery power is also making its way into freight locomotives; German operator DB Cargo has ordered 100 part-diesel, part-battery locos from Japanese firm Toshiba. DB already operates small numbers of switchers with battery packs.

Keith Fender

Batteries cheaper than hydrogen?

For much of Europe, where rail networks are already largely equipped with overhead electric power, the battery EMU is a simpler and cheaper alternative to both hydrogen and diesel. Rapid charging technology means battery EMUs do not need to use the overhead wires for long to fully recharge, making them good for several more hours of operation before needing another recharge. So, a 50- to 100-mile route with overhead power available at both ends can use a battery EMU, with a short recharge at either end.

A major study funded by the German government which also involved train makers and operators, published in July 2020, showed that battery equipped EMUs were likely to be 35% cheaper to buy and use than the hydrogen-powered equivalent. They were also cheaper than the diesel trains they will replace. As all hydrogen-powered trains also have batteries, like the battery EMU, the difference comes down to the cost of the different power systems and of the fuel used.

While supporters of hydrogen power for trains point to the fact that the only “emission” is clean water, this ignores the fact the hydrogen has to be made somehow. Some hydrogen is available as a by-product of industrial activity, but nowhere near enough is available to power trains in most countries. The “green” approach to making hydrogen uses electrolysis to split the hydrogen atoms from water, but this requires lots of electricity — around 3 times as much as a conventional electric train. Studies published in the United Kingdom suggest that for a train to generate 1kilowatt of power at the wheel, using this “green hydrogen,” requires 3.4 kilowatts of grid power for the electrolysis. An EMU taking traction current from an overhead wire would need 1.2 kilowatt from the grid for 1 kilowatt at the wheel.

Keith Fender

Hydrogen development spreading

Hydrogen-powered trains may see service elsewhere. The Alstom iLINT has been tested successfully in the Netherlands during 2020 and approved for use in Austria as well, although so far, no trains have been ordered in either country. Alstom has recently announced a contract to build a different type of train powered using the hydrogen technology pioneered in the iLINT; six Coradia Stream units will be built for Milan-based Ferrovie Nord Milano, a regional rail operator in Italy. Swiss-based Stadler has a contract to build five narrow gauge, hydrogen powered trains to replace diesel on the Zillertal railway in Austria. These are due for delivery in 2022.

Other manufacturers are still at the prototype stage. Siemens announced in 2018 it was planning to debut a hydrogen fuel cell-powered version of its new Mireo commuter rail EMU, the Mireo Plus H, using fuel cells supplied by Canadian firm Ballard Power Systems. Siemens has recently announced the prototype train will take another four years before passenger testing can begin in southern Germany, south of Stuttgart, in 2024. In late 2020, Spanish manufacturer CAF won a contract from the European Union to convert an older Spanish EMU to hydrogen fuel cell operation as part of work to create new Europe-wide industry standards for the safe use of hydrogen

In the UK, a demonstrator hydrogen-powered train, branded HydroFlex, was converted from an older EMU by its owner, leasing company Porterbrook, using Ballard technology. It took to the rails in September 2020. A separate project to convert older trains to hydrogen power using Alstom’s technology is also underway in Britain; the Alstom Breeze trains should be ready for use by 2024. Studies by Network Rail, which runs the British rail network, suggest hydrogen-powered trains could replace diesel trains on some longer rural lines that will not be electrified. Overhead electrification is preferred as the means of removing most diesel operation.

Outside Europe, Chinese train builder CRRC has built hydrogen powered trams which entered service in 2019, also using Ballard’s technology. In South Korea, Hyundai Rotem is developing a hydrogen-powered train. And in Japan, rail company JR East, Hitachi, and auto maker Toyota are planning to build a hydrogen fuel cell-powered train.

How fast can battery-and-hydro-powered MU’s move? Are they faster than diesel?