NEW YORK — If current Class I railroad volume growth efforts don’t bear fruit, railroads will either have to turn to transcontinental mergers or try to shrink themselves to prosperity.

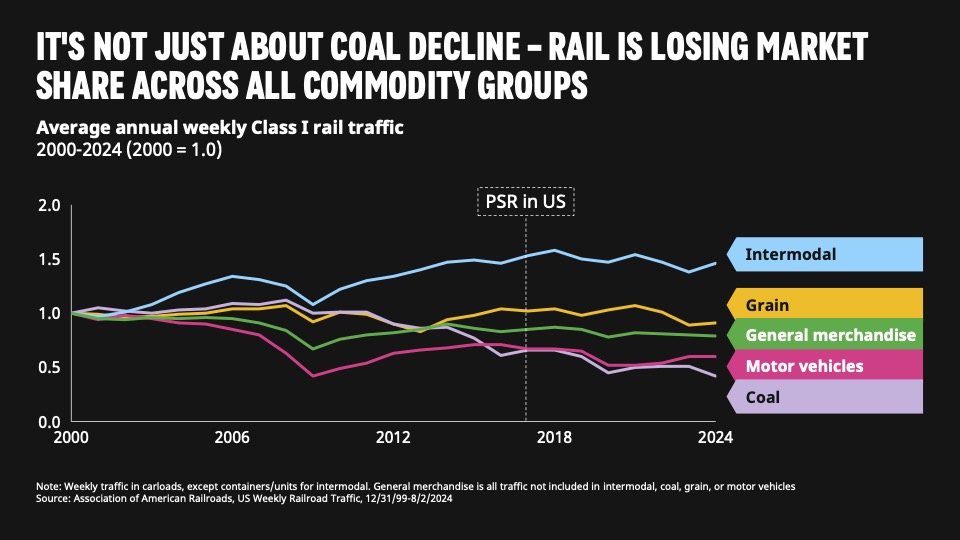

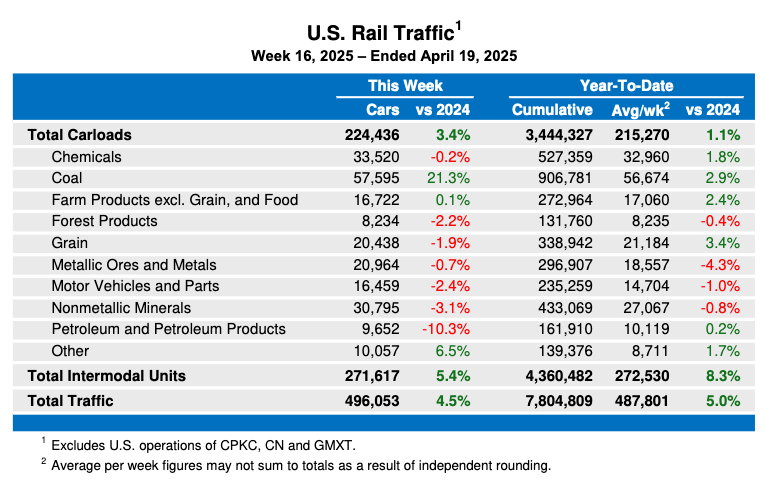

That’s the conclusion Oliver Wyman consultant Adriene Bailey has reached after examining trends of declining traffic and anemic revenue growth as railroads continue to lose market share to trucks.

Eventually, a lack of growth will put pressure on railroad CEOs to boost earnings, she says. “CEOs worth their salt will not accept being relegated to running glorified utilities,” Bailey says. So they’ll either push their teams to get creative and figure out how to increase revenue and profits — or they’ll be replaced as investors demand change.

“What are our options if rail fails to grow? Oliver Wyman sees two remaining choices,” Bailey told the RailTrends conference earlier this month. “The first would be that the four largest Class I railroads merge into two transcontinental systems like Canada. The second would be for the Class Is to shrink to greatness and share a lot more infrastructure.”

Current Surface Transportation Board regulations frown on major mergers. But Bailey says that creating two U.S. transcontinental systems would eliminate redundant costs, significantly expand the single-line service that shippers prefer, and open up so-called watershed markets that aren’t served well today because origins and destinations within a couple hundred miles of the Mississippi River are short hauls that are not attractive to the eastern or western railroads.

“Mergers may reduce some competitive options for shippers, but railroads will have a vested interest in keeping the volume from going back to trucks,” Bailey says.

Absent mergers, the big railroads could reduce costs by sharing main lines, yards, and terminals where it’s feasible, Bailey says. These arrangements are nothing new, she says, pointing to examples like the BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Joint Line along Colorado’s Front Range and the Directional Running Zone that Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Kansas City use in the Fraser and Thompson river canyons of British Columbia.

“These sharing arrangements exist today for a variety of reasons, but if growth remains elusive, the pressure to shrink to prosperity will intensify,” Bailey says.

“But the larger question is, do the railroads really want to shrink to greatness, further reduce their future options, their competitiveness against trucks, and their role in the North American economy,” she asked.

The answer seems to be no, given that all of the Class I railroads say they are now focused on volume growth.

“The railroads seem to be embracing what we see as the top three areas of opportunity: intermodal, rail-centric industrial development, and short line growth,” Bailey says. “I’m more than pleased to hear the Class I CEOs actively talking about volume growth. But I do not yet see evidence that the industry is delivering on the top two things that are required to tip the scales permanently in the favor of rail: A serious and demonstrated commitment to transit reliability and making it much easier to transact.

“More concerning is I’m not yet sensing that investors and perhaps even boards have bought into that strategy — and we should not underestimate the influence of the investment community on where public companies focus their efforts,” she says.

It’s no surprise, Bailey says, that railroads are not growing when the strategy has been to raise rates without making improvements to service.

Continued cost-cutting and price-taking won’t deliver the profit growth needed for the industry, according to Oliver Wyman’s analysis. What will maximize shareholder value, Bailey says, is adopting volume growth strategies while becoming more customer friendly.

“Is there a reason the industry isn’t figuring this out? Some might ask if there really isn’t any growth to be had. Isn’t this a fool’s errand? It’s a good question and I’ll say it once more. What I’ve heard loudly and consistently from shippers: ‘We want to put more freight on rail. We just can’t stand the difficulties and the frustrations it involves.’”

The stakes for the industry are high.

“Failure to achieve industry growth aspirations will have very unpleasant consequences if the industry fails. And this indeed would be an epic failure giving up on nearly two centuries of painstaking value creation,” Bailey says. “Railroads would be forced to shrink, lose jobs, tear up infrastructure. And I believe for myself and for many of you here in this room, that is not a story we want to see told to future generations.”

RailTrends is sponsored by independent analyst Anthony B. Hatch and trade publication Progressive Railroading.

A decade ago, I made this case for the future in terms of a fictional narrative.

https://blerfblog.blogspot.com/2014/01/2040.html

Maybe, I need to update it…like a Christmas Carol. Things that “will be” or “might be”….

Oliver Wyman and Adriene Bailey have been singing this song for at least 15 years. She appears at every conference and forum about RRs, and sings the song.

Her conclusions are not supported by any evidence whatsoever. It is at best a hypothesis, untested in the Real World in which RRs – and Investors operate.

No one listens. Why? Because she and the Consultant world have no skin in the game. To whom do you think the Directors of a RR would listen? Some consulant? Or the company’s stockholders?

If CEOs can’t make the case for the long term, higher net present value, to the investors, then they are lazy and stealing money.

Making the case for change and growth is really hard work.

They need to get busy.

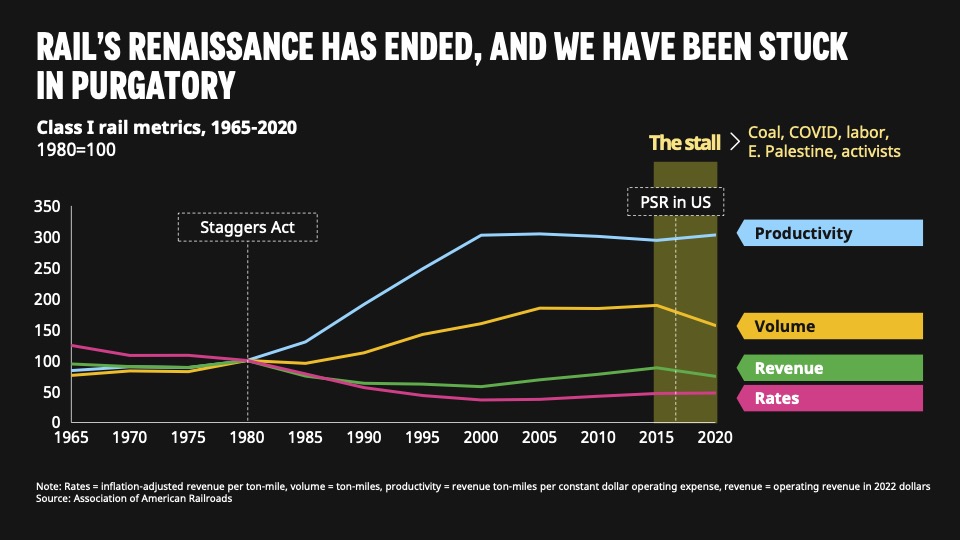

PSR was solving the wrong problem!

https://blerfblog.blogspot.com/2023/12/how-to-kill-rail-renaissance-and-maybe.html?m=1

…and for those keeping score at home…I wrote this a year ago.

Failure to invest in growth.

Let’s start with electrification….

https://blerfblog.blogspot.com/2023/04/i-built-train-performance-calculator.html?m=1

Well exactly how long did it take Ms. Bailey and all the other geniuses at OW to figure this one out???

At my very first Santa Fe IBU staff meeting after I came aboard in January 1990, I heard Mike Haverty say, “You cannot starve a railroad into prosperity”.

During the next five years we filled both main lines up with new profitable intermodal traffic until we ran out of capacity in 1995.

Then we went out and double tracked Abo Canyon and finished doubletracking all the way to Kansas City.

Rob Krebs chased after David Goode to do a deal, but old Dave just had his heart on Conrail. Well, we see where that got him.

And I suspect with BNSF the best is yet to come at places like Barstow and Livingston. The second coming of Quantum may be another new paradigm like no other.

For more details read my cover story in the Fall issue of Classic Trains. I am a bona fide intermodal revolutionary.

I guess I look at BNSF as both half full and half empty with the railroad being privately owned having the greatest leverage to truly take a long term view on there investment as well as the risk.

…

So half full is the intermodal and the investments that they are making is legit and will only grow traffic. On top of it, The Port of LA/Port of Long Beach have been making huge investments with expanding on dock to rail service with a fair share of automation happening dockside. In other words, Port of LA/Long Beach/BNSF will continue to be a power player on a fair share of American container traffic and with BNSF investments it should capture more domestic containers between spaces, especially in Southwest like Phoenix, etc.

..

So half full, do you really see the efforts to capture loose car traffic? or build a stronger industrial base around that traffic? Everyone did a great job adding unit train loading facilities to consolidate existing grains. But, BNSF like the rest ran train crews off the rail on hint of downturn and then can’t capitalize on traffic that is given to them.

With all due respect Santa Fe and BNSF had/have very strict contribution standards. We were “offered” a lot of traffic we simply chose NOT to handle. I also don’t think you want to handle random new business if you have main line capacity issues which BNSF is aggressively solving with new construction. This conundrum is NEVER as simple as it looks from the outside.

And crews were always free to “mark off” to find more lucrative income producing opportunities whenever business was slow. Many of them found additional work in agriculture and construction. The question you have not answered is how many operating employees were “run off” and how many simply left of their own volition to go make more money elsewhere.

The biggest problem with loose car railroading was the first mile-last mile issue. That was the impetus behind the establishment of the carload logistics parks like Alliance and Fontana (read my article).

Perhaps we should outsource the random boxcar business to JB Hunt and see what our trucker friends can do with it. I personally think the loose car business is overrated from a contribution standpoint.

And maybe we’re not as dumb as people like you think we are. Remember that the GM body plant in Willow Springs, IL was once one of Santa Fe’s most lucrative customers in the Chicago Terminal. But after it was closed, we manage to turn the site into one of the most extraordinarily profitable operations on the entire railroad.

Option #3: Reregulation and the return of railroads to glorified utilities. If you cannot balance franchise management and the National interest then the government can mismanage it for you.

Railroads have been in shrink mode ever since Staggers. How can you grow a business when physical plant has been shrinking? How can 3 mile, 15,000 ton slugs going 40 mph ever provide carload service and compete with trucks?

50 years ago refrigerator cars from California would be delivered on the 4th morning to the Hunts Point market in NYC. Today, almost ZERO produce ships by rail. Locally there is virtually no carload traffic.

Lastly note the çproductivty”

…productivity trend. Executives have squeezed the workforce to the point where experienced workers have left. The next level is one man crews.

The railroads have been atrophying for a century with track mileage down to 140,000 from an apex of 250,000 in the 1910s. “Too much” track was declared a national scourge and rules put in place for triage of existing infrastructure and resistance to new track. Somehow we need to push past that ethos.