DENVER – The last vestige of north-south passenger trains serving the Mile-High City disappeared 50 years ago when Santa Fe’s ragamuffin round trip to the east-west main line at La Junta, Colo., didn’t transition to Amtrak. But work is well under way to change that.

The Southwest Chief and Front Range Passenger Rail Commission is making significant progress in assembling the partnership and financing building blocks to establish a multiple-frequency passenger rail corridor where the population is booming and the need for mobility is exploding.

At the organization’s monthly public board meeting on Friday, members approved resolutions defining future priorities and opportunities. They include:

Pledging coordination with host railroads and RTD commuter rail

Early last week, commission Chairman Jim Souby met with representatives from Amtrak, BNSF Railway, Union Pacific, Colorado’s Department of Transportation, and Denver’s Regional Transportation District.

“It was a very productive meeting,” Souby says. “We discovered there are options to make passenger service much more convenient getting through Denver than we originally thought, because of all the time we might spend turning trains around getting into [stub-ended] Denver Union Station.”

A massive real estate development in the early 2000’s eliminated the station’s rail approach from the south; overcoming this is a significant challenge to be solved.

After Souby’s report, members voted to issue a memo of understanding confirming that the commission intends to explore sharing of costs, equipment, and possible future commuter rail corridors to the fullest extent possible.

Recommending a route from Fort Collins to Pueblo

As part of environmental requirements to ensure that all possible route options are considered, an 88-page “Alternatives Evaluation Report” issued last December outlined the pros and cons of the best three options:

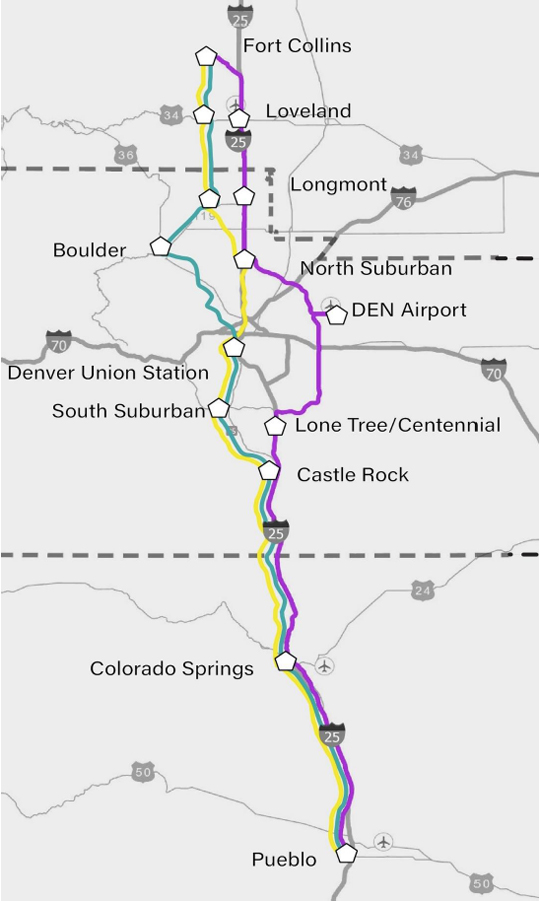

— Placing tracks in the middle of or adjacent to Interstate 25 the entire distance, with a branch to Denver International Airport, shown in purple on the adjacent map;

— Utilizing existing highway and RTD transit rights-of-way north of Denver and the BNSF-UP rail corridor to the south, shown in yellow;

— A BNSF route north of Denver and the BNSF-UP tracks to the south, shown in green. This is the only alternative directly serving the city of Boulder, which last saw passenger service in 1967.

After some debate, the members passed a resolution indicating preference for the third option. Their strong support was based on a comparatively positive evaluation, and that two commission-sponsored Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvement (CRISI) grants have been awarded for parts of the route and are awaiting execution.

One grant seeks to model capacity needs under various freight and passenger frequency scenarios to determine what additional trackage and signaling might be necessary to keep the full route fluid from. The other, somewhat related grant seeks to determine infrastructure requirements if Amtrak were to establish a through-car connection with the Southwest Chief at La Junta.

The “Joint Line” south of Denver was once operated as a directional, double-track railroad by owners Santa Fe and Denver & Rio Grande Western, but portions were abandoned when traffic ebbed in the 1970s. The route, now single track in many locations, has recently been in a state of flux with once-dominant coal traffic tailing off.

Souby says, “It’s an existing right-of-way with capacity modeling studies about to begin, and it continually comes up in talks with political leaders and Amtrak, BNSF, and RTD officials. It also stands the best chance of getting federal support and will make our legislative efforts much clearer.”

Vice Chairman Sal Pace adds that the route fares best in the study of alternatives, and notes Colorado’s Economic Development Commission last week approved $7.5 million for the acquisition of UP’s former Burnham Yard south of the Denver station [see “Digest: VIA operations continue …,” Trains News Wire, April 19, 2021].

“That makes entry easier for passenger rail into Denver Union Station,” he says. Pace also says RTD’s challenge to complete its Northwest Rail Line (or B Line), which is only operating 6 miles of a proposed 41-mile route through Boulder to Longmont, Colo., has created an opportunity for shared investment. He adds, however, “Designating this as the one we favor still doesn’t preclude us from looking at the alternatives.”

Urging support of legislation creating a Front Range Passenger Rail District

Commission members generally thought recommending a route was especially important in advance of a Colorado Senate Transportation and Energy Committee hearing on the bill, SB21-238, taking place Tuesday, April 27, at 2 p.m. MDT. More information is available here.

The law would give counties served by the Fort Collins-Pueblo passenger corridor the ability to tax those who benefit from the service [see “Colorado bill would create Front Range Passenger Rail District,” News Wire, April 12, 2021]. This would create a predictable funding source for construction and operations, and heads off objections from other parts of the state that don’t want to pay for someone else’s regional improvements.

Forming a rail district would also facilitate creation of an operating entity that could promote the service and negotiate with the railroads and Amtrak. The model has proved to be especially effective as implemented in California’s three joint powers authorities and Maine’s Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority, which established the Downeaster corridor north of Boston in 2001.

The legislation doesn’t set tax rates; that comes after voters learn specifics. This is why the bill seems to have enthusiastic bipartisan support from local Democratic and Republican leaders and why the commission feels its enactment now is crucial.

Analysis: ‘Chief’ issues laid groundwork for commission, remain significant

At a “media roundtable” with local and national participants on April 12, Amtrak CEO William Flynn and President Stephen Gardner pointed to a Front Range corridor as a prime element of the company’s forward-looking “ConnectsUS” initiative. The map released as part of that initiative shows a Cheyenne-Fort Collins-Denver-Pueblo route but no connection with the Southwest Chief. “The map is not exclusive nor prescriptive,” Amtrak has said in public statements.

But the Colorado commission was born out of the adversity caused by the physical deterioration of portions of the Southwest Chief’s route. Communities bought in to the concept advanced by BNSF Railway’s Matt Rose and late Amtrak CEO Joseph Boardman that a local match could fuel federal grants to rehabilitate the tracks.

When current Amtrak management floated came a plan that would have substituted buses over the segment in question — which the company had previously promised to help rehabilitate — the response was strenuous objections from local politicians of both political parties, the communities, and the former incarnation of the commission. The caveat that Amtrak’s COVID relief funding is tied to restoring daily long-distance trains is a descendent of previous activism and concern over the fate of the Chief.

At Friday’s meeting, commission members learned about the progress of work resulting from grants it championed, including installation of positive train control east of La Junta, and how the New Mexico Department of Transportation is working to allow RailRunner dispatchers to take over duties from BNSF Railway further east along the Chief’s route.

The commission also voted unanimously to reapply for a previously denied grant that would replace the last 34 miles of bolted rail west of the Kansas-Colorado state line, and between Garden City and Dodge City, Kan. This would complete 364 miles of rehabilitation that began with an inspection trip in 2012. The matched funds secured since then have totaled more than $100 million.

As Souby remarks, “Getting the Southwest Chief route up to snuff in Kansas and Colorado has a big bearing on the train’s success and future as well.” It also will likely play a role the feasibility of a plan to route the Chicago-Los Angeles train from La Junta through Pueblo and down to Trinidad, Colo. Doing so would effectively extend the Fort Collins-Pueblo corridor to Albuquerque, N.M., and points west.

The additional connection possibilities would not only strengthen patronage, but effectively restore rail options that existed 50 years ago when Denver and Colorado Springs passengers were often able to reach Santa Fe destinations well beyond this proposed corridor’s finite boundaries.

Not going north to Cheyenne and south to La Junta would be a waste, as it would connect 3 east-west routes, thus increasing travel possibilities.

Operating the Southwest Transcontinental Corridor via Pueblo is an idea first promoted by the United Rail Passenger Alliance in the late 1980s. It made sense then and it makes even more sense now.

And the Front Range Corridor absolutely should go north to Cheyenne.