FORT WORTH, Texas — BNSF Railway’s increasing use of longer trains is the most visible element of a broader effort to boost efficiency and productivity.

Since the onset of the pandemic BNSF has been combining trains, blending different types of traffic in the same trains, and operating more double-length loaded unit trains of grain and coal.

But unlike the other Class I railroads, BNSF’s move toward handling its tonnage on fewer but longer trains is being done on a more limited basis, as it aims to strike a balance between productivity and service. “We’re considering both customer and BNSF needs,” Chief Marketing Officer Steve Bobb says.

When traffic tanked last spring during pandemic-related shutdowns, BNSF aimed to maintain service levels and reduce crew exposure to the virus. So the railroad began blending traffic as a way to maintain train length and reduce the number of train starts and therefore the number of crews needed.

As volume rebounded in June, running combined, blended, and longer trains enabled BNSF to handle the growth without having to wait for furloughed crews to return to duty, a process that can take up to 30 days.

And as intermodal business ramped up due to a combination of dramatically increased port and parcel traffic, using longer trains provided more capacity and was one way to help limit congestion, particularly on the Southern Transcon linking Southern California with the Midwest.

“Right now, our customers want capacity,” Bobb said in an interview last month. “And so our service performance might not be elegant, but the ports and BNSF are moving a lot of stuff. So it’s really about being effective in providing throughput for our customers.”

BNSF has a number of what Bobb calls “set plays,” where it aims to combine trains without affecting dwell or train velocity.

For example, BNSF’s international intermodal trains that depart the Port of Los Angeles pass the nearby Watson Yard, which is a destination for ethanol trains that originate in the Midwest. A 5,700-foot unit train of empty ethanol tank cars – complete with its power – will be coupled behind a 7,300-foot stack train bound for Chicago. They’ll run combined across the Southern Transcon as far as Oklahoma, Kansas, or Missouri. Then they’ll go their separate ways, with the ethanol train running back to its origin terminal and the intermodal loads going on to Chicago.

BNSF is combining all sorts of other traffic into double-length trains for parts of their trips across the railroad: Domestic and international stack trains, high-priority Z-symbol premium intermodal trains with Q-symbol intermodal trains, domestic-domestic and international-international combos, and international intermodal with empty grain unit trains. It’s even running some double-length coal trains straight from Powder River Basin mines. BNSF says it’s combining fewer than 10% of its trains on a typical day.

BNSF also is blending traffic in ways it only rarely did before the pandemic: Merchandise and intermodal, merchandise with autos, and even intermodal, merchandise, and coal.

Finally, BNSF has abolished some merchandise trains and folded their traffic into other trains, further reducing crew starts and the number of active trains.

The operational changes are not entirely new to BNSF. For several years, the railroad has been running double-length empty coal and grain unit trains, as well as a mixed intermodal-merchandise train linking the Pacific Northwest and Texas. It also regularly ran a few double-length loaded grain and coal trains. But the pandemic accelerated blending of traffic and building longer trains. “It was an acceleration of necessity, given what unique pandemic challenges were to us,” Bobb says.

BNSF’s train crew employment levels have historically risen and fallen with volume. But as a result of its operational changes, BNSF in the first quarter this year was able to handle a 7% increase in traffic with 11% fewer engineers and conductors on the payroll than a year ago.

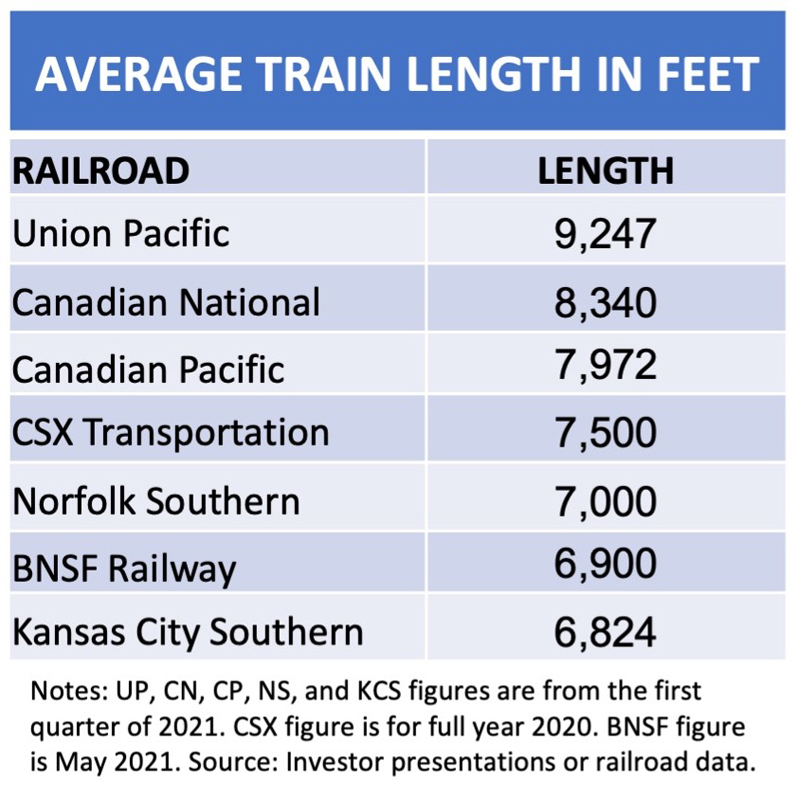

Yet despite running some trains that exceed 14,000 or even 15,000 feet, BNSF’s average train length in May was 6,900 feet, up just 200 feet from a year ago. And BNSF’s use of longer trains pales in comparison to Union Pacific, which has boosted train length by 30%, to 9,247 feet, since adopting a Precision Scheduled Railroading operating model in late 2018.

Yet despite running some trains that exceed 14,000 or even 15,000 feet, BNSF’s average train length in May was 6,900 feet, up just 200 feet from a year ago. And BNSF’s use of longer trains pales in comparison to Union Pacific, which has boosted train length by 30%, to 9,247 feet, since adopting a Precision Scheduled Railroading operating model in late 2018.

Bobb says BNSF has always been focused on being a low-cost, efficient railroad with a bias for growth.

“Our customers want us to provide reliable and consistent service. That’s what they pay us to do,” Bobb says. “And our customers also need us to be efficient, so that we can be sustainably competitive, because if we can’t compete, then we can’t provide them the service they need to serve their customers and their markets.”

Last year BNSF’s 61.6% operating ratio was the most improved among the Class I systems.

“There’s nothing wrong with driving an operating ratio lower,” Bobb says. “I like to think that we have a cost focus on that one. What we don’t want to do is start thinking about the operating ratio from a, ‘What business do we want to do?’ approach. We don’t want to go out and prune business … to create a lower operating ratio, because if there is a profitable growth opportunity, we’re going to focus on that, not on that business’s inherent operating ratio.”

The emphasis on longer trains is just one aspect of BNSF’s drive to improve safety, reliability, and efficiency, Bobb says. Increased use of technology – including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and predictive analytics – is at the heart of the other initiatives.

More sophisticated equipment and track inspections, combined with analysis of the detector and inspection data, has allowed BNSF to take a proactive approach to railcar and track maintenance. The result has been a reduction in delays and service interruptions from things like brake failures, bad actor freight cars, slow orders, and problems with crossovers. “We’re really happy with the results we’re seeing,” Bobb says.

Other examples include better integration between BNSF and customer computer systems, reducing truckers’ transit times through touchless gate technology at intermodal terminals, and testing technology that will allow truckers to bypass terminal gates.

What these efforts have in common, Bobb says, are that they reduce costs for BNSF while saving customers’ time and improving the customer experience.

(Editor’s Note: Watch for an in-depth feature story on BNSF’s operating changes, scheduled for the November 2021 issue of Trains.)

Distributed power makes all this possible.

Without DP, the engineer making a mistake in train handling ends up in emergency when the train jerks and breaks a knuckle.

BNSF should be applauded for it’s IOR, Intelligent Operational Railroading

BNSF has the right approach to this PSR, unlike UP all they really worry about is stock holders. Not so much about customer satisfaction.

There will be a point where a train is long enough, for safety reason, there should be no less than two crew members on a though fright or unit train.

Keep going on the path you are heading BNSF, for your employees and your customers big or small.

Good news