WASHINGTON — Federal regulators seem likely to impose a new reciprocal switching rule that would open up more carload traffic to competition between Class I railroads.

During two full days of hearings that wrapped up on Wednesday night, the Surface Transportation Board was sympathetic to shipper complaints about a combination of high rates and poor service – as well as their suggestions that reciprocal switching would be a remedy for both problems.

The board was skeptical of Class I railroad arguments that widespread reciprocal switching would snarl operations, worsen service, and reduce investments that would help divert freight from road to rail.

The reciprocal switching proposal would allow shippers served by one Class I railroad to gain access to a competing Class I railroad nearby. The current railroad would be forced to hand off the shipper’s traffic at the closest interchange. The idea is to introduce rail competition where none exists.

The current reciprocal switching rule, which dates to 1985, isn’t used because it requires shippers to prove that their serving railroad is engaging in anticompetitive conduct. The proposed new rule merely would require the shipper to show that reciprocal switching either is in the public interest or is necessary to provide competitive rail service.

Board Chairman Martin J. Oberman floated the concept of a two-tiered reciprocal switching rule. The first tier would expand reciprocal switching at hundreds of terminals nationwide where it currently exists due to merger-related conditions or voluntary agreements with some shippers. In those cases, all shippers within the terminal area would be able to gain service from two or more Class I railroads. The second tier, aimed at rural shippers, would introduce reciprocal switching using a mileage-based radius that would effectively bring them closer to interchanges.

Shipper complaints

A string of shipper groups – representing food and beverage companies, wheat growers, glassmakers, mineral miners, and scrap metal firms — told the board on Wednesday that the implementation of Precision Scheduled Railroading in the U.S. since 2017 has made local service less frequent, less reliable, and less resilient due to massive job cuts.

Meanwhile, the shipper groups said rates have gone up, particularly at locations served by a single Class I railroad.

Shipper groups said reciprocal switching would introduce competition, reduce rates, and improve service, based on their experience at facilities served by more than one railroad.

Former STB Chairman Daniel Elliott, representing the Private Railcar Food and Beverage Association, said that rail competition would create an incentive for the incumbent railroad to provide better service and enable shippers to negotiate better rates.

Reciprocal switching also would bring new carloads to railroads and help replace declining coal revenue, Elliott says.

Sole-served shippers have lost bargaining power, which has resulted in contracts that favor railroads, says Karyn Booth, a lawyer representing scrap metal shippers. Railroads gain minimum volume commitment from shippers, she says, but in most cases contracts no longer provide shippers with any service commitments.

Chemical producer Diversified CPC International receives better service at its plants that have access to more than one Class I railroad, Sandra Dearden, a consultant representing the company, told the board.

Rates are important, she says, but become a secondary concern when railroad service problems force a plant to shut down due to missed switches or cars that are delayed in transit, like loads that were stuck for 10 days at Norfolk Southern’s yard in Decatur, Ill. Diversified CPC’s plant in Sparta, N.J., is located on regional New York, Susquehanna & Western, which offers connections to both CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern. Due to poor NS service, Dearden says the company has shifted all of the plant’s outbound traffic to CSX.

But Diversified CPC doesn’t have options at its NS-served plant in Petal, Miss., and says the railroad has been demarketing traffic. Citing a lack of capacity, NS increased the rate for inbound propane shipments by 24.5% on the 235-mile route from the CSX interchange at Birmingham, Ala., to Petal, Dearden says. That’s increased production costs and puts the plant’s future in jeopardy, she says.

If reciprocal switching were available, Dearden says Diversified CPC could use a Canadian National interchange at Hattiesburg, just 10 miles from its plant. A current NS reciprocal switching agreement in Hattiesburg applies to just one customer, not Diversified.

Another chemical producer, Indorama Ventures, told the board that it has had to curtail or stop production at two of its plants in the Southeast and one plant in the Northeast due to unreliable rail service over the past 14 months. “This is devastating to our business,” Lane Baker, one of the company’s logistics managers, told the board.

The company has had to resort to using trucks in some instances, and due to longer transit times Indorama increased its railcar fleet by 10% and plans to add to the car fleet by another 8% this year due to inconsistent service.

“With reciprocal switching, we could keep our supply chain moving by engaging another Class I railroad,” Baker says.

Warnings from railroads

Ray Atkins, a lawyer for Norfolk Southern, told the board that if shippers’ concern is about rates, then the STB should regulate rates directly rather than impose reciprocal switching. And if the concern is about service, reciprocal switching won’t help because it’s likely to make service worse, he says.

The STB already has tools to address unreasonable rates and poor service, Atkins says. He encouraged the board to adopt current proposals that would streamline rate cases and use its power to order reciprocal switching at locations with persistent service problems.

NS Chief Operating Officer Cindy Sanborn and CN Chief Operating Officer Rob Reilly separately told the STB that reciprocal switching would add operational complexity, increase dwell and transit times, and require additional locomotives, crews, and freight cars — all of which would increase dwell and transit time while creating congestion. They also said reciprocal switching would reduce visibility of incoming traffic, making it harder to plan their operations and ensure that they have enough capacity.

Sanborn told Oberman that she appreciated that he was considering limiting reciprocal switching to terminals where it already occurs, which would affect 105 locations on NS. That’s down from more than 750 locations that would be affected if reciprocal switching were expanded to customers within a 30-mile radius of a terminal.

But she used Decatur, Ala., where NS and CSX interchange traffic today, as an example of a location that would be challenged by an expansion of reciprocal switching. Sixteen out of 30 shippers in Decatur are currently covered by reciprocal switching agreements that likely arose from prior rail mergers.

Sanborn says CSX and NS locals exchange cars at the four-track Old Yard, adjacent to the junction of their busy main lines on the approach to the single-track drawbridge both railroads use to cross the Tennessee River. The yard, with a capacity of 22 cars per track, often is full and can’t be expanded because it’s hemmed in by main lines, a neighborhood, and a grade crossing.

“If every customer were open to reciprocal switching coming over CSX, once we filled up the Old Yard with interchange — and had too much for the Old Yard to hold at interchange — cars would begin to back up,” Sanborn says. “And there are times already today where that occurs.”

In a lengthy back-and-forth, Oberman tried to understand why NS and CSX couldn’t handle additional reciprocal switching traffic when their locals already serve customers in the area, switch their traffic, and build blocks for road trains to pick up. Every day NS and CSX coordinate interchanges and switching all across their systems, he pointed out.

“It is a fairly complex operation and it is a location that is very difficult to be able to take on any additional work,” Sanborn says.

Sanborn explained that the NS New Yard remains fluid when the railroad handles the entire move. Inbound traffic that arrives on NS road trains quickly connects to the railroad’s own locals, she says, while the timing of the railroads’ interchanges is not coordinated and require additional handling.

Oberman was skeptical. He said the STB would take a case-by-case approach to customer requests for reciprocal switching and suggested that the board would not approve more reciprocal switching arrangements than a terminal could handle. And he said he hoped the threat of reciprocal switching would prompt railroads to “up their game” and work with shippers to resolve service problems.

Chilling impact on investments

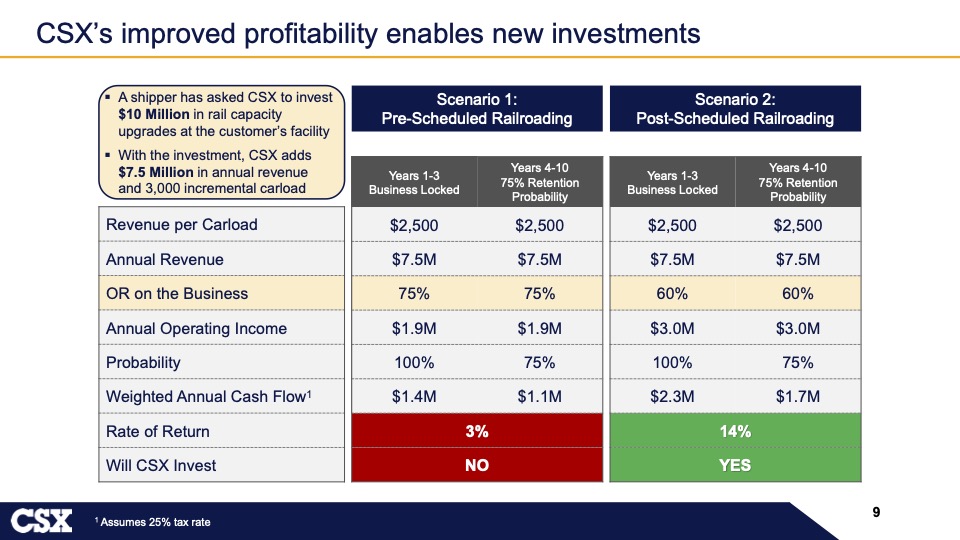

Railroads have argued that reciprocal switching would act as a disincentive for capacity investments. CSX Chief Financial Officer Sean Pelkey, in the last presentation of the two days of hearings, showed a concrete example of how reciprocal switching would discourage investment and curb the growth of rail traffic.

In 2018, 1.1 million ton miles of freight moved on trucks at lengths of haul greater than 500 miles, the range where railroads can best compete for traffic. Shifting that traffic to rail, Pelkey noted, would save 5.6 billion gallons of fuel and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 62 million tons.

CSX has changed its executives’ long-term incentive plans to focus on growth and is aggressively working to attract new traffic, Pelkey says, pointing to the railroad’s acquisition of chemical trucking company Quality Carriers, its proposed acquisition of Pan Am Railways, and a series of recent announcements of new plants to be built across the CSX system.

The railroad’s improved financial performance has enabled it to pursue traffic and investments that would have been unattractive before it adopted Precision Scheduled Railroading in 2017, he says.

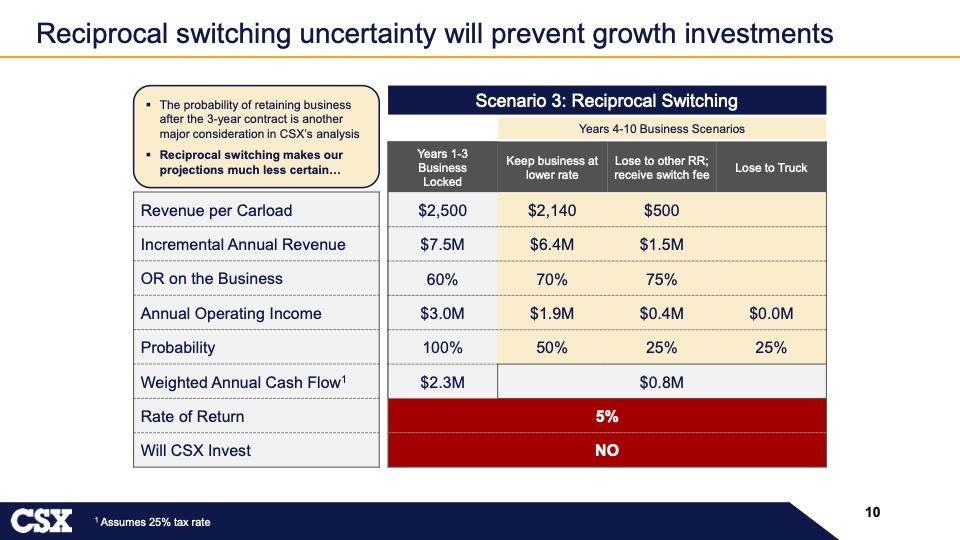

Reciprocal switching would upend CSX’s growth plans and stifle investment, Pelkey says.

In a hypothetical example, a shipper asks CSX to invest $10 million in rail capacity upgrades at the customer’s facility. CSX anticipates gaining $7.5 million in revenue annually from the 3,000 carloads the new facility would generate. The business is guaranteed for three years.

With CSX’s operating ratio at 75%, the investment would not make financial sense and the project would not move forward. But with CSX’s operating ratio at 60%, the project would clear the railroad’s internal investment hurdle and would get the green light. “CSX can now make the investment with the customer to drive growth to the railroad and away from the highways,” he explains.

That would change if reciprocal switching were introduced, Pelkey says, because CSX could no longer be certain that it would retain the traffic over the long term. After the three-year contract expires, CSX might keep the traffic but at a lower rate. Or CSX might lose the business to a competing railroad through a reciprocal switch.

Either way, CSX would reject the project because the return on investment would be unacceptably low.

“I can tell you very simply that the board’s proposal, if adopted, will impact the math we do when exploring investment opportunities that support growth,” Pelkey says. “The more uncertainty there is, the more difficult it is to justify growth investments.”

He adds: “The board has a choice. It can have a broad vision promoting genuine competition, particularly allowing us to take trucks off the nation’s highways with all the public benefits that follow. It can do this by creating a regulatory environment that protects the right to the long-haul, and a lawful amount of differential pricing, while encouraging growth investments. Or the board can have a narrow view of competition, forcing synthetic competition through reciprocal switching, compressing railroad rates and returns, meaning it would be more difficult to increase overall market share. And we’d expect the current rail piece of the pie to keep shrinking.”

People should remember that the FCC tried something similar with the phone companies back in the middle 1990’s to promote high speed internet access.

They forced the local Bell’s to price wholesale rates for last mile residential DSL and to allow other ISP’s to place their equipment in phone company CO’s to service these residential customers. (in this case switching IP traffic, not rail cars)

What you ended up with was the local Bell’s started skimping on last mile investment, since they were forced to share it, they refused to invest in it. It got so bad that Verizon was tearing out the last mile copper to residentials that subscribed to non-regulated services (like fiber).

I see the same happening here. If you force the host railroad to extend wholesale trackage rights to a competitor, and if the railroad only has 1 customer on the line and the reciprocal agreement is a loss leader, they will abandon the line or let it go into very deferred maintenance.

Fortunately, residential internet found other ways to get their service (cable, wireless, etc.). I would surmise that shippers will throw their hands up at reciprocal switching due to a reduction in service and push them harder towards trucks, or to relocate to where choices are more available.

If the RRs served their customers reliably and didn’t try to stick it to them on rates & accessorize charges, they’d be happier & the RRs wouldn’t likely be here. They have billions to buy back & inflate their own share prices, but no money for *anything* else (better service, wages, physical plant.) They’re basically crying that competition isn’t a good thing & it would make their heads hurt to try to figure this out. They’ve done this to themselves & they deserve whatever the unfavorable (to them) outcome is.

If the problem is caused by the high cost of local delivery to the customer, then re-allocate the revenue share to reflect that. If part of the profit for the long haul carrier is sacrificed to cover the local switching costs at the originating end, then the allocation of costs should consist of all three costs calculated separately, actual switching costs at both ends and what’s left for the “over the road” haul. While this would reduce the allocation for the long haul carrier, it would equalize the return on investments for switching costs for both carriers. What’s good for the goose should also be fair for the gander. Providing a fair return required to provide good service at both ends of the haul should incentivise both carriers to provide good service.

Railroads complain “Our yards will be flooded with new traffic”. Isn’t that a good thing?

So Wall street has encouraged higher profits on poorer service, and now will desert rail investment as the chickens come home to roost. Who would have suspected.

as a 30yr railroaded I can tell you that the class ones have brought this on by themselves. since PSR, service has plummeted . I can show you customers who used to get 5 day a week service who are lucky to get service one day a week under PSR. we wait for cars that used to come to us next day now can sometimes take a week. get rid of PSR and the current crop of CEOs a make the customers important and the problems will go away

Why should captive shippers(that have always been served by only one railroad, mind you) get the option to now have more than one choice on who transports their product?

GERALD — You ask a question with no good answer, like any/ all issues of government regulation of monopolies or semi-monopolies. I suppose we could start with this: railroads should serve their customers, unlike now. The alternative (which seems to be happening) is more government regulation.