WASHINGTON — An error in which the worker in charge released track occupancy protection — “due to degraded performance from his excessive workload” — led to a March 2022 incident in which a Caltrain commuter train struck three hi-rail construction vehicles, the National Transportation Safety Board concluded in a final accident report released on Tuesday, Feb. 27.

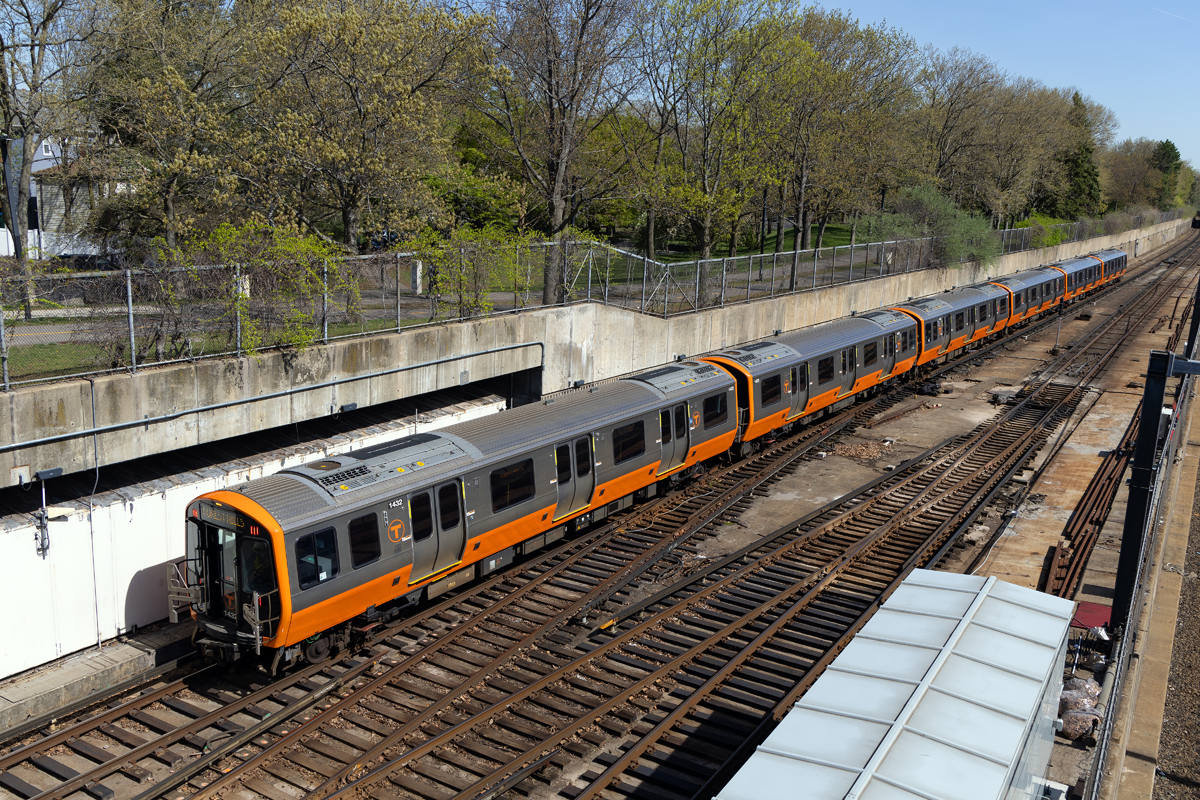

The March 10, 2022, incident in San Bruno, Calif., sent eight people to the hospital, including one construction worker who sustained serious injuries; destroyed the three construction vehicles; and triggered a fire that spread to one of the Caltrain cars [see “Caltrain collision with ‘on-track equipment’ ignites fire …,” Trains News Wire, March 10, 2022]. Caltrain estimated property damage exceeded $1.4 million.

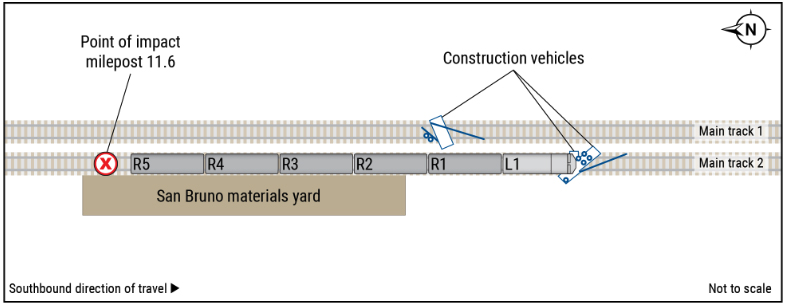

The incident occurred at about 10:31 a.m., and involved a San Jose-bound train that was traveling at 64 mph on Main Track 2 about a quarter-mile from the collision site, but had slowed to about 43 mph by the time it struck the first construction vehicle, about 13 seconds after the engineer began an emergency brake application.

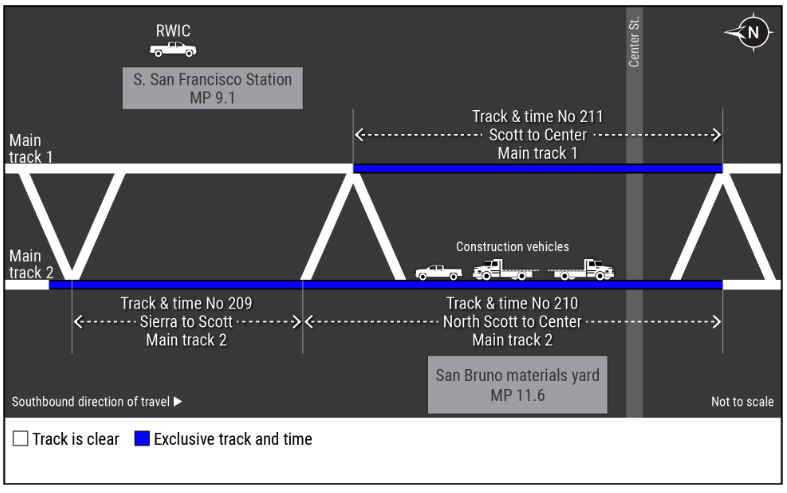

The crew, working on catenary pole installation, had begun work at 9:29 a.m. and had been given exclusive track-and-time protection on Main Track 2 in an adjacent area until 4 p.m., and in the area including the collision site until called — meaning the worker in charge or dispatcher would communicate release of that protection. Additional track-and-time protection was granted at 9:47 a.m. in the same area for the adjacent Track 1; that protection was released at 9:54 a.m., and the protection for the section of Track 2 where the crew was still working was released at 9:58 a.m., although a required communication between the worker in charge and a subgroup coordinator did not take place. With the dispatcher’s system indicating there were no construction vehicles in the area, Train No. 506 was routed through the area on Track 2 about a half-hour later.

An NTSB review subsequently determined that the worker in charge had worked seven consecutive days prior to the accident, with shifts of 11 to 14 hours on the five days immediately prior. The worker told the NTSB that while his official 40-hour schedule did not include weekends, a typical week included a minimum of 75 hours of work, often including weekends. NTSB workers found he had worked 15 of the previous 16 days, and the off day had been spent at doctors’ visits and physical therapy.

In the wake of the incident, Caltrain created a fatigue risk management plan, limiting employees to work weeks of 60 hours or lesss, and working with labor organizations or contractors to limit work weeks and hours. It also created new procedures requiring supplemental shunting devices or a signal procedure known as signal system interruption to provide additional protection for on-track construction activities, and a redundant safety procedures to verify the release of track and time authority.