Different camera lenses show the world differently. Modern zoom lenses, including many that can change magnification by a factor of 10 or greater, make it easy for photographers to change their perspective. Zoom lenses also make it too easy to forget just how much the twisting of the zoom ring can affect the outcome.

Here’s the temptation: you consider only the framing of the scene when you zoom in or out while making your composition. Framing is certainly important, but you can change the framing of your scene just as easily by walking forward or backward without touching the zoom ring. What’s also changing as you twist that ring is the perspective, and those twists can drastically alter the relationships of the pictorial elements within the viewfinder.

Technical Descriptions

Allow me a digression into lens vocabulary (without delving too deeply into optical physics). We most often discuss lenses in terms of their focal lengths, a unit of measurement typically given in millimeters. Like a lot of optical concepts, this is best explained by a diagram, where the focal length is shown as a lowercase and italicized ” f.”

There are good reasons for using the term “focal length” when dealing with a single optical system. For one size of film or image sensor (an “optical system”), the focal length of the lens determines such characteristics as the magnification, depth of field, and angle of view. In photography, however, we encounter the problem of having many different optical systems, each one based on a different-sized piece of film or image sensor.

For example, a 50mm lens on a Canon EOS 5D camera (with a “full frame” image sensor) has a considerably different angle of view than the same 50mm lens on a Canon EOS 50D camera (which employs a smaller “APS-C” image sensor). On the 5D, the 50mm lens has a horizontal angle of view of 40 degrees. The 40-degree angle of view means that, in the picture’s longer dimension from one edge of the frame to the other, the 50mm lens takes in 40 degrees of the full 360-degree horizon. On the smaller sensor of the EOS 50D, the 50mm lens only takes in 25 degrees. (This is the same angle of view as an 80mm lens on the 5D, leading to the use of the term “1.6 cropping factor” with Canon’s APS-C cameras: 50mm x 1.6 = 80mm.)

The table (right) compares focal lengths for equivalent angles of view on both full-frame and 1.6x APS-C formats. The focal length is the diagonal length of the film or image sensor. The line near the middle of the table with a 45-degree angle of view shows what is considered “normal.” Everything with a larger angle of view (and smaller focal length) is considered a “wide angle” lens, while everything with a smaller angle of view (and larger focal length) is considered a telephoto lens.

When thinking about how a certain lens depicts a scene, the angle of view becomes a very important factor. If we shift our thinking about lenses away from focal length and onto angle of view, this notion becomes more apparent.

Telephoto

Compared to a normal lens, a telephoto lens takes in a much smaller area. In doing so, telephoto lenses effectively “magnify” the scene, which has the visual effect of compressing the distances between objects. This can have a tremendous impact on the way a photograph portrays the elements within a scene and their relationships with one another.

Consider a railroad crossing where the circular yellow sign is 105 feet from the crossbuck. Starting with a normal lens (in this case, a 50mm lens on a full-frame camera with a 40 degree angle of view), I position myself such that the circular yellow sign and its post completely fill the frame from top to bottom. The crossbuck by the tracks, which is roughly the same height in real life, appears only 25 percent as high.

Next, I switch to a 100mm telephoto lens with a 20 degree angle of view. I have to take seven steps back for the circular yellow sign and its post to fill the frame from top to bottom. Even though I’m farther away, the crossbuck now appears to be 35 percent as high. I can increase the effect by backing up even more and using an even more pronounced telephoto lens, like a 200mm with only a 10 degree angle of view, in which case the distant crossbuck appears to be 60 percent as high as the closer sign.

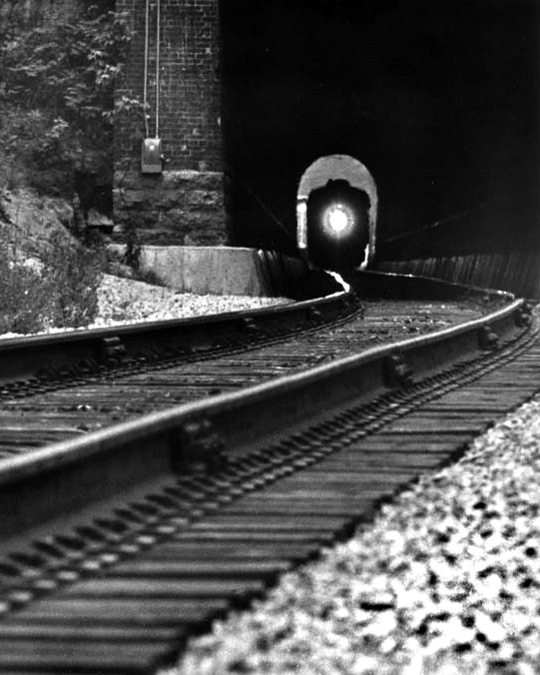

John Gruber, long-time Trains contributor and president of the Center for Railroad Photography & Art, helped usher in the use of telephoto lenses in railroad photography with his “remarkable movielike sequence of photos” showing Milwaukee Road passenger train No. 58 coming through the tunnel at Tunnel City, Wisconsin, in 1961. Trains devoted four pages to those photos that year, which “looked through” the tunnel by effectively compressing the distance between one portal and the other.

Once scorned for the way they distorted reality, telephoto lenses are now a staple of railroad photography, especially in head-on photos where their compression characteristic can make distant mountains or other scenery appear much closer.

Wide Angle

Wide angle lenses, on the other hand, “see” a much wider area. In the process, they also “magnify” the distances between objects in the frame, making them appear to be farther apart. This magnification also can affect the way a photograph depicts the relationships of the different elements within the scene.

Going back to our railroad crossing, I switch to a 24mm wide angle lens with a 74 degree angle of view. Compared to my photo with the normal lens, I have to take four steps forward for the circular yellow sign and its post to fill the frame from top to bottom. Now, however, the crossbuck appears to be only 12 percent as high as the closer sign. Also note the other differences in this sequence of photos, made at the Southwest Madison Avenue crossing in Corvallis, Ore. The wide angle lens takes in 74 degrees of the horizon, fully showing the former Southern Pacific freight house in the background at right. The longer telephoto lens captures only 10 degrees of the horizon, and the old freight house is no longer visible.

The wide angle lens exaggerates the distance between the signs, and this is very important to consider while making photographs. One example is when you want to juxtapose a train with something much smaller, like flowers. In his photo of Southern Pacific No. 5623 on the Niles Canyon Railroad in California, Alex Ramos used a wide-angle lens and got very close to the flowers. The combination allowed the flowers and the locomotive to appear in the photo at about the same size. Think of how different the relationship, and hence the photograph, would have been if Ramos had used a telephoto lens where the locomotive would have appeared much larger compared to the flowers.

Normal Lens

What then, of the normal lens, the lens with the view most similar to that of the human eye? Once considered by many to be the only acceptable lens for photographing railroads, today the so-called “normal” perspective often elicits a yawn and barely a pause on the super zoom lenses quickly racking out from ultra wide to super telephoto. Don’t be fooled, though. Normal lenses are responsible for many of the greatest railroad photographs of all time, and remain powerful tools in the hands of skilled photographers.

Three of the presenters at 2010’s “Conversations about Photography” conference: Frank Barry, Jim Brown, and Tom Taylor used normal lenses extensively in their work. All three photographers mostly used normal, fixed (non-zooming, non-interchangeable) lens cameras for many years of their photography careers. To make interesting photos, they relied on their familiarity with their format and their ability to “fit” the world into it, rather than into a host of different lenses.

Remember the Relationships

Regardless of the focal length or the angle of view, photography is about visual relationships, both finding them and creating them. Different lenses interpret the world in different ways, which we can use to portray different visual relationships between the objects around us. It’s important to understand these differences in order to use them effectively.

Be deliberate when choosing the focal length (and, hence, angle of view) for your railroad photos. While zoom lenses can promote laziness, they also can be very powerful tools when used effectively. Just consider the relationships and try to see the picture in your mind’s eye before looking at it through a lens. David Plowden does this to such great effect that he now says he takes one picture-the one he wants-and then moves on to another challenge. We should all aim to do the same. If we do, there would be a lot less wasted effort in the field and at the computer afterward.

Trains contributor SCOTT LOTHES is a writer and photographer in Corvallis, Ore. He is project director for the Center for Railroad Photography and Art.