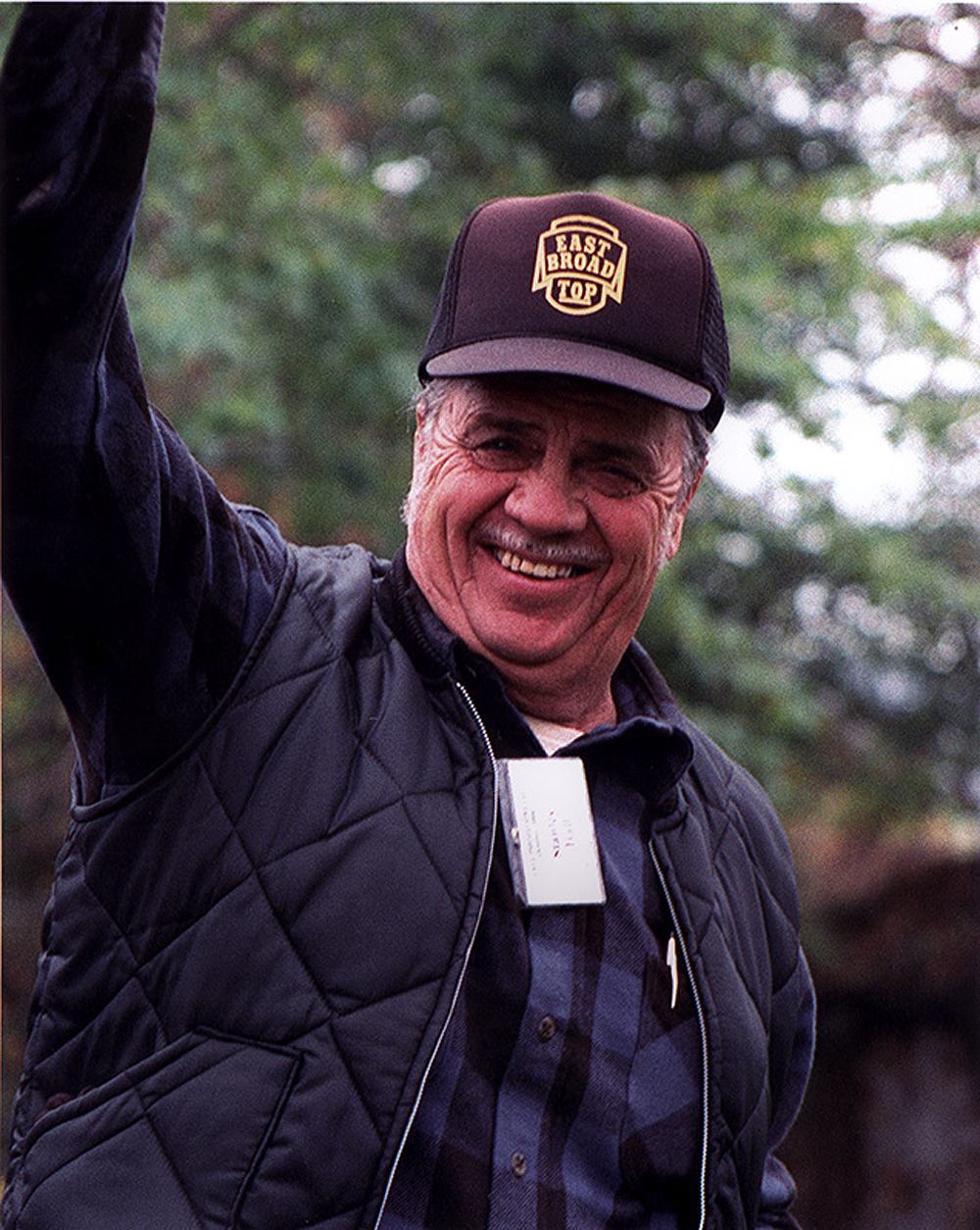

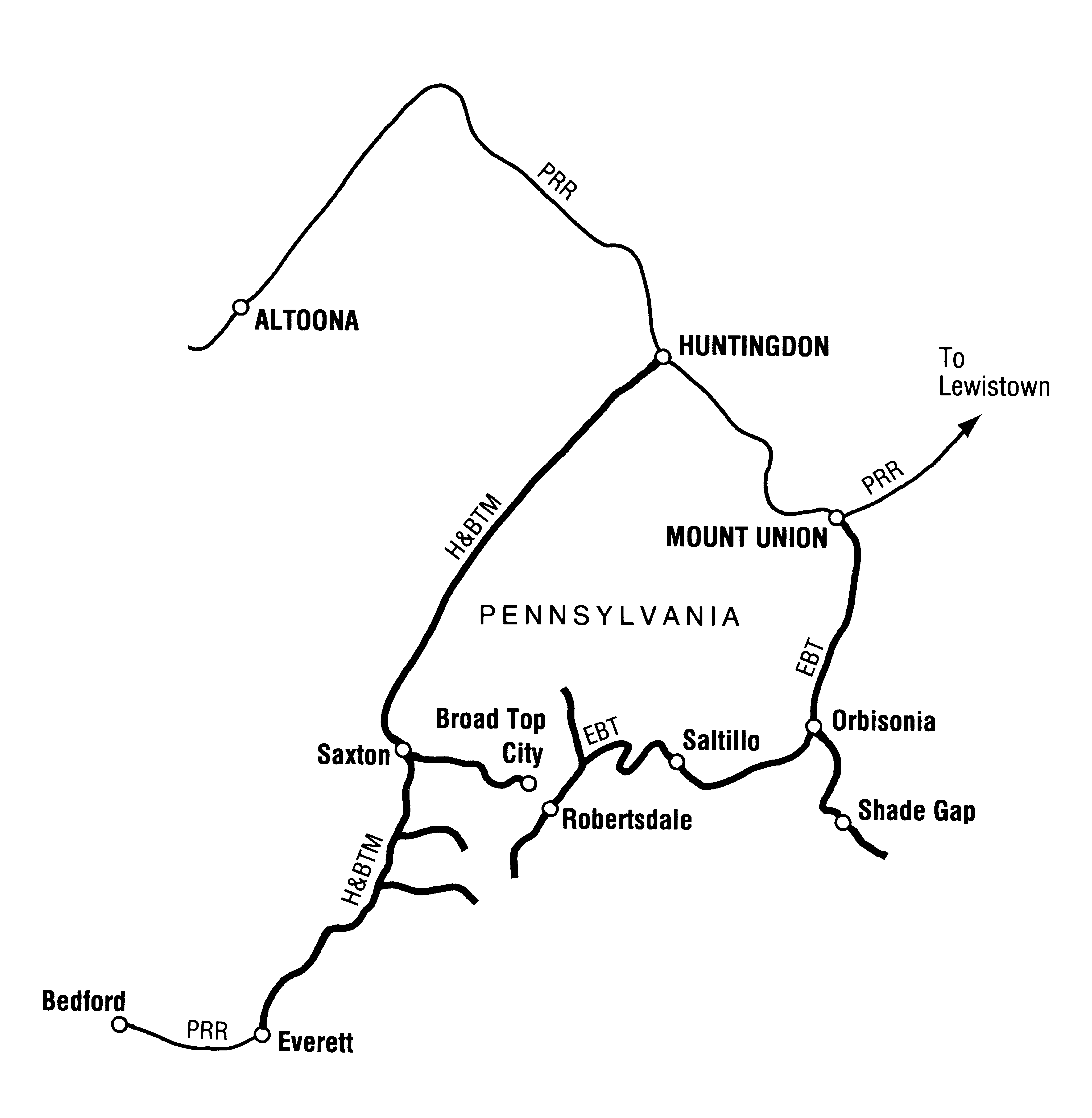

Stanley G. Hall has worked 49 years within earshot of the grade crossing that takes Meadow Street over seven tracks at the throat of the East Broad Top Railroad’s yard in Rockhill Furnace, Pa. He worked first on painters’ ladders, next in the cabs of the railroad’s Baldwin Mikados, then at a desk in the well-worn office on the first floor of the 1906 station. It’s an employment record that fits the narrow-gauge line’s traditions perfectly, mixing pride and pathos, engine oil and elbow grease, fury and affection. And it’s a record he hopes to extend at least to a nice, round 50 years.

East Broad Top hired Hall as a painter in May 1960, three days after he graduated from high school and three months before the longtime coal hauler reopened as a tourist line. In the years since, he has done every job imaginable, from picking up trash and “swamping the commodes,” as he puts it, to maintaining and running engines, rerailing coaches, razing derelict buildings, and negotiating with the Federal Railroad Administration to keep at least one of the line’s six Mikados steaming. He has been the railroad’s general manager since the 1987 retirement of the East Broad Top’s last operating vice president, C. Roy Wilburn, a holdover from the common-carrier era.

Hall heard plenty of East Broad Top whistles even before he came to work for the railroad. When he was a boy and the 33-mile-long railroad was still hauling coal from the mines on Broad Top Mountain, his family moved to a farm alongside the tracks. He and his sister would often run out to wave at train crews, who would wave back, and sometimes kick off chunks of the engines’ coal, which he and his sister would collect and take home.

In 1960, Hall met the man he still refers to as “Mr. Wilburn.” By then a salvage dealer named Nick Kovalchick (Joe’s father) had owned the railroad for four years, but had scrapped only a few sidings. With the twin boroughs of Rockhill Furnace and Orbisonia due to celebrate their bicentennial, the committee planning the festivities asked Kovalchick if he would pull an engine out of the roundhouse for the event. Instead, he offered to run trains on a five-mile stretch of the line. Hall, hired for $1.25 an hour, started painting the station and the four coaches that had not been sold after the railroad ended passenger service in 1953.

He worked alongside old-time employees who had been called back, and he was eager to learn from them.

“You kept getting underfoot for a bit, and they realized that if you helped them, it made their life a little bit easier,” he says.

He was soon helping to keep the Mikados in good repair and operating the machinery in the shops.

“One thing I learned from them,” he says, “was that there was a right way, a wrong way, and the East Broad Top’s way, and that’s the way you do it. Like it or don’t like it, it’s what works.”

He eventually learned to run not only the line’s Mikados and Fairmont track speeders (several from the 1920s) but also the homebuilt 1924 inspection car and the M-1, the line’s unique and handsome 1927 Brill gas-electric unit, which has a 12-seat passenger compartment as well as room for mail and express. When a trolley museum opened on the right-of-way of what had been the railroad’s Shade Gap branch, he learned to run trolleys, too.

The early years were busy. Then as now, the line was open weekends from June though October, but initially tourist traffic was so brisk that in July and August the railroad ran six trains a day, seven days a week, and had about 20 employees. Besides the 56-ton No. 12, which dates to 1911, the railroad rehabilitated three of the other Baldwins: Nos. 14 and 15, 75-ton sisters built in 1912 and 1914, respectively, and No. 17, which dates to 1918 and is one of a trio of superheated East Broad Top engines weighing in at more than 80 tons.

Video by Wayne Laepple

One Saturday afternoon, two flues began leaking in the only engine still operable at the time, No. 15. It was losing so much steam, Hall says, that he had to go rescue it with the M-1. Hall pulled a coach behind the Brill unit to round out the day’s runs, then called his engineer and his hostler and opened up the front end of the Mikado, which was still too hot to work on comfortably. Inside the firebox was even hotter.

“We got a bunch of wet burlap and threw it on the grates, and green pine planks,” he says. “We ran two rods from the firebox in, so we knew which flues were broken. I made four plugs out of green white pine, eight inches long, and drove them into those two flues ’til you couldn’t drive them any further. We drove them in with a welding mask on, and an air compressor, and an air hose running in so you could breathe,” he says, laughing. “We didn’t know a thing.

“We drove those plugs in and fired her back up. We ran for two weeks with those plugs in that boiler. Inside the firebox they burned off even with the flue sheet, and just petrified. At the front end, they just stayed like they were. They didn’t blow out either, and we carried 175 pounds of steam behind them.”

The pine plugs, he says, were a trick he learned from a local man who operated a steam saw mill.

There have been terrifying moments, too. Years ago, an engineer brought No. 17 and its train all the way back from the far end of the line with neither injector working, and the intervening decades have done nothing to dull Hall’s anger.

“When that injector doesn’t come on the second time, your brain ought to go in gear and you ought to pull the fire where you are. You don’t keep pulling your injector and getting it hotter and hotter and blowing your water away. You’re not taking any in, you’re blowing it away.

“I cut the lever on the coaches right here in front of the station, while the train was moving and I was screaming at the top of my lungs,” Hall says. He climbed in the cab and “headed for the ball field, and wouldn’t you know it, there was a county league having a ball game. I was going to blow a locomotive up with 400 kids there. We slammed it into reverse and I pulled it up over by those stone abutments that they uncovered when they took the [coal refuse]. Elmer Barnett and I pulled the fire. It seemed like it took two hours, but we pulled it in two minutes. Literally dumped her out.”

Linn Moedinger, president and chief mechanical officer of the Strasburg Rail Road, has known Hall since the 1970s and advises him frequently on locomotive matters. He says any steam railroad will encounter problems, but at the East Broad Top, “they know how to get out of trouble.”

And what really sets the EBT apart, Moedinger says, is that Hall has kept alive the culture of the railroad, which is still operated largely by people raised in the state’s rural southern Huntingdon County.

“It is a family. It’s one of the unique things about the East Broad Top that has been brought forward, first by Mr. Wilburn and now by Stanley. … It’s one thing to preserve the nuts and bolts,” Moedinger says. “It’s another thing to have the culture preserved, and Stanley has been a very big part of that.”

The railroad has been dormant since 2012.

I road the East Broad Top several times near the end of their tourist train service. Even though it was only a 5 mile run you experienced what an old time local train service was like. The people of East Bod Top we’re friendly and proud of their little railroad. I wish it was still running but it’s location in rural central Pennsylvania makes it hard for them to get enough passengers to make it work. It is far from Pittsburg or Philadelphia and is not in an area that attracts a lot of tourists that help support other railroads nearer to bigger cities or near larger tourist attractions. If it were to reopen they would have to work hard to market it to non railfans and tour bus operators to try and get the volume of business to make it work. It can be done. One only has to look at some of the steam train tourist operations out west that are successful and yet are relatively far from large cities.