Electrification of railroads

North American freight trains are powered by diesel locomotives. Before the diesels, steam engines did the work. Electric trains have a niche hauling passengers in the Northeast. Everyone knows this short history of motive power development, but it’s not quite the whole story.

Early electrification of railroads

“Diesels,” of course, are properly called diesel-electrics because it’s electricity (produced by an on-board generator turned by a diesel engine) that actually powers their traction motors.

The suitability of electric motors for traction was exploited starting in the late 1880s by urban transit systems and, later, the new interurban railways. Electric current was supplied to the cars from central power plants via a system of transmission lines, substations, and overhead wire or (on elevated, underground, or private rights-of-way) third rail. Electric current was “collected” from a wire by a trolley pole, and from a third rail by a shoe.

Around the beginning of the 20th century, the established line-haul railroads began to look to the new technology to solve an age-old problem: smoke from their steam locomotives. In urban areas it was a nuisance, and in tunnels a life-threatening menace.

It was in Howard Street tunnel, beneath downtown Baltimore, that the first “steam” road electrification took place. The Baltimore & Ohio’s installation of 1895 showed that electrification was practical for heavy-duty railroading, thus launching a 40-year era of its expansion. Electrification offered many advantages besides relief from smoke.

Electrification of railroads: Main lines and terminals

Cleaner, faster, smoother running, more powerful, and easier on track than steamers, electrification had only one major negative: high initial cost. To electrify a line, a railroad had to invest in motive power and the extensive infrastructure to support it. Also, a juice system would ideally be intensively used to make the investment worthwhile.

Nevertheless, after the B&O, railroads began 23 electric installations (not counting experimental or interurban-like systems) from 1905 to 1931. These operations amounted to approximately 2,279 route-miles and (bespeaking electrification’s suitability for high-density lines) 5,923 track-miles.

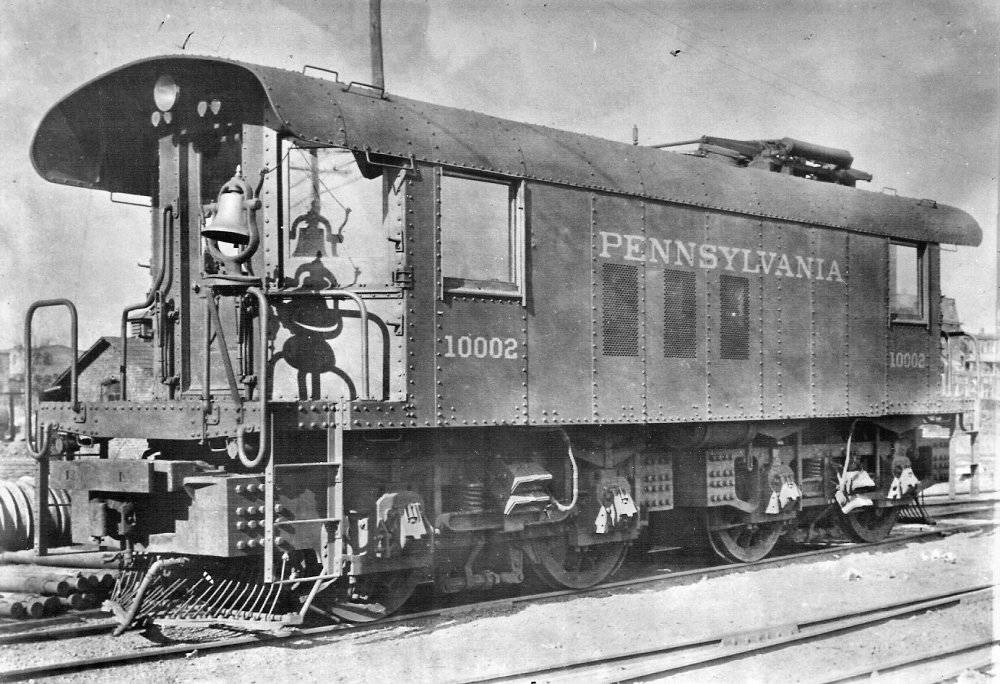

Spurred by smoke abatement laws, New York Central and Pennsylvania (and subsidiary Long Island) electrified their New York City operations in the first decade of the 20th century. Electric traction allowed extensive use of tunnels to reach the roads’ Manhattan terminals.

These systems (and two others) were the only major steam-road third-rail installations, though rapid transit often employed third rail. They also used direct, as opposed to alternating, current.

Compared with AC, DC offered superior motors (and a proven transit record), but inferior long-distance transmission qualities. Debates over which system was best continued until the advent of better AC motors in the 1930s ended the construction of new DC systems, as did ACs dominance in the commercial power network.

New Haven’s electrification of 1907 was one of the few systems to encompass all types of operation: passenger, freight, commuter, and switching. This comprehensive approach, and the use of 11,000-volt AC power supplied by overhead wires (or “catenary”), was the model for the Pennsylvania’s 2,150 track-mile empire, installed 1915-1938. Much of these systems are in use today.

Elsewhere, wires went up to do specific jobs. Tunnels prompted short stretches of electrification on Grand Trunk, Michigan Central, Boston & Maine, and Canadian National (on which Montreal commuters rode until 2020, when the line was shut down for conversion to a light rail system). Mountain districts, which often included tunnels, hosted “motors” on Norfolk & Western, Virginian, Great Northern, and Milwaukee Road, whose two isolated sections on its Pacific Extension totaled 663 route-miles and lasted into the 1970s. Commuters got catenary on Southern Pacific (east of San Francisco), Illinois Central, Lackawanna, and Reading, and still enjoy its benefits, except on SP. Smoke avoidance alone led to electrification in the Cleveland Union Terminal area.

Electrification of railroads: Dieselization dooms electrics

Dieselization spelled the end of the electrification era. The new motive power technology combined the smoke, traction, and maintenance plusses of “straight” electrics with greater flexibility and lower initial cost.

In the decade after World War II, seven systems were shut down, victims of diesels, aging electrical equipment, and changing traffic patterns. Some extensions to electric commuter lines occurred, but by 1981 the plug had even been pulled on Conrail’s ex-PRR freight-only lines.

Today, there are only a handful of full-size freight electrics at work on mine and power-plant railroads.

Electrification has seen an upturn in mass transit applications, as many U.S. cities built light rail lines in the 1980s and 1990s. In 2000, Amtrak completed a massive 156-mile electrification project between New Haven, Conn., and Boston, which allowed its high-speed Acela Express and other electric trains to run the entire length of the Boston-Washington Northeast Corridor. In California, electrification of the currently diesel-operated Caltrain commuter rail line between San Francisco and San Jose is slated to be completed in fall 2024.

Perhaps federal urban air-quality regulations will lead to electrified districts, just as smoke ordinances did a century ago.

This was originally published in June 1993 issue and was entitled, “Wired rails: Electrification.” Updated by Trains staff.

The photo is of Washington Union Station, not Hoboken, viewed from K Tower. On the left appears to be the recently arrived Liberty Limited.

Diesels should have been an interm phase between pursuing mainline electrification.

Since the railroads love to run long, and heavy trains. Electrics are perfectly suited for this type of work. As they have a much longer torque band than diesels do.