While the Russians were staging their annual parade in Moscow’s Red Square on May Day 50 years ago, Amtrak was born at Washington’s L’Enfant Plaza. The company came into the world under a death sentence known only by a select few in the railroad industry and the Nixon White House. The plan was to create a cash-strapped passenger railroad destined to fail from starvation.

Amtrak was created because competition from interstate highways and the airlines had driven down revenues, pushing passenger losses yet higher. Penn Central had the biggest deficit of all. As Jervis Langdon, a trustee of Penn Central, recalled, “Hauling passengers was killing railroads in the Northeast.” Therefore, Judge John Fullam, who was presiding over its bankruptcy, ordered the railroad to shut down its passenger trains.

Since Penn Central ran the originating segments of such trains as the Seaboard Coast Line’s Silver Meteor, the other roads depended on it. Slowly Congress began to realize that passenger service was costing all the nation’s railroads, and soon it took over the rail passenger business of all but three railroads by creating the National Railroad Passenger Corp., or Amtrak.

The Federal Railroad Administration then assigned one of its young staffers, James W. McClellan, to slim down the national passenger network. McClellan killed such notable trains as the City of New Orleans and the Wabash Cannonball, so when Amtrak opened for business on May 1 it was operating one-third of what had been the nation’s passenger fleet.

Railroad CEOs, such as the Burlington Northern’s Louis Menk, hated passenger trains. Not only did the trains lose money, they complicated operations, delaying freight service and beating down tracks. Amtrak was supposed to be an experiment, and Menk and others conspired with the Nixon White House to starve Amtrak for the subsidies it needed to be a successful enterprise, thereby giving the administration an excuse to declare the experiment a failure and kill Amtrak. Unknowingly Congress had aided that compact by failing to provide enough subsidies at Amtrak’s start.

Roger Lewis, an affable man who had been head of General Dynamics, a defense contractor, was named president. Unfortunately, Lewis had been fired from General Dynamics and always seemed reluctant to stand up to Nixon and possibly get fired a second time. Lewis, who had no experience in railroading, also seemed reluctant to make decisions and did not get out on the property other than to ride the Broadway Limited to Chicago or even take the Metroliner to New York.

Lewis and his board hired Harold Graham of Pan American World Airways as marketing vice president. Graham and others on the staff came from airlines and thought only they knew how to deal with passengers and viewed railroaders with disdain. “We’re having to correct all these old practices that developed over the years,” Graham said. He attempted to make trains like airliners, with all cabins, seats, and meals looking the same, and he took diners off the New York-Boston trains and club cars off Metroliners. He even was determined to fulfil the dream of many airline people and kill off first class.

On his arrival Graham launched a nationwide advertising campaign declaring that “The Trains Are Back.” He cut fares on some routes that drew in enough new passengers to cut a few trains’ losses. People began responding in masses, and even more soon joined in as a fuel shortage unexpectedly gripped the nation, forcing many motorists to take the train. Lines of customers soon were forming at ticket booths across the country, causing ridership to climb by 15% each year.

Although Graham had the right strategy, Amtrak was totally unprepared. Coaches and stations were dirty. Some trains soon were booked for months and seats were oversold. And many trains were running late. “Amtrak’s on-time records look so bad they can make you throw up,” complained Anthony Haswell, who headed the National Association of Railroad Passengers.

Passenger cars, especially those from the hard-pressed Northeastern roads, needed repairs and refurbishments. But what funds Congress appropriated went for decorating the cars rather than heavy maintenance, which they needed every four years. Finally, a year and a half after Amtrak’s start, Frank S. “Pat” King, Amtrak’s operations vice president, launched a heavy maintenance program, but by then one quarter of the fleet had missed its time in the shop. It never caught up.

“They came through with psychedelic decorations, but the toilets don’t work, and the air conditioners don’t work”, said W. Graham Claytor, Jr., president of Southern Railway and a devotee of passenger trains. His road was one of the three that did not immediately turn over their passenger operations to Amtrak.

By 1974, Amtrak’s third birthday, more than one-fifth of its car fleet was out of service and those running often had no lights or air conditioning. Amtrak was short of cars. Presidents’ Day weekend that year between 5,000 and 7,000 passengers on the Northeast Corridor were forced to stand shoulder-to-shoulder, some on the platforms between the cars.

When Congress talked of providing subsidies to the company, the administration insisted that Amtrak needed to be profitable and fend for itself. It even told Amtrak that long-term planning was unnecessary because eventually it would be cut down to only a few routes or perhaps disbanded altogether.

Congress had become so alarmed at Amtrak’s poor performance in 1972 that it worked to have Lewis’ salary by more than half, but it did little more because Nixon controlled Amtrak’s board. Finally, in the spring of 1974 Lowell Weicker, a Connecticut Republican who sat on the Senate Commerce Committee, read a magazine expose´ of Amtrak’s troubles, and got enough directors’ votes to oust Lewis.

He was replaced by Paul Reistrup, who had run passenger operations on the Baltimore & Ohio and Illinois Central. Congress began insuring that Amtrak got government money, and Reistrup began using the fresh cash flow to turn around operations. Among other things he bought Penn Central’s Beech Grove shops and acquired bi-level cars for long-distance trains.

Of course, Reistrup did not make Amtrak profitable, and Congress has never recognized that passenger trains never can make money and must be run as a public service like the highways. Congress’ other great mistake was—and still is–its failure to make Amtrak a line item in each year’s federal budget so it no longer is treated as an experiment.

Underfund something, and when it collapses, blame it. I see this with any number of entities, most notably with public education: underfund it, then blame it, or the teachers, and then offer privatized alternatives like charter schools – the purpose of which isn’t education, but profits! Compared to Europe, where rail traffic is considered vital (yes, I know that Europe has a vastly different geography than we do), but America has trouble with “public interest” vs. private desires for profits. We continually get this one wrong, and the public suffers, even as private interests continue to grow richer on public money. Thanks for this good and accurate article.

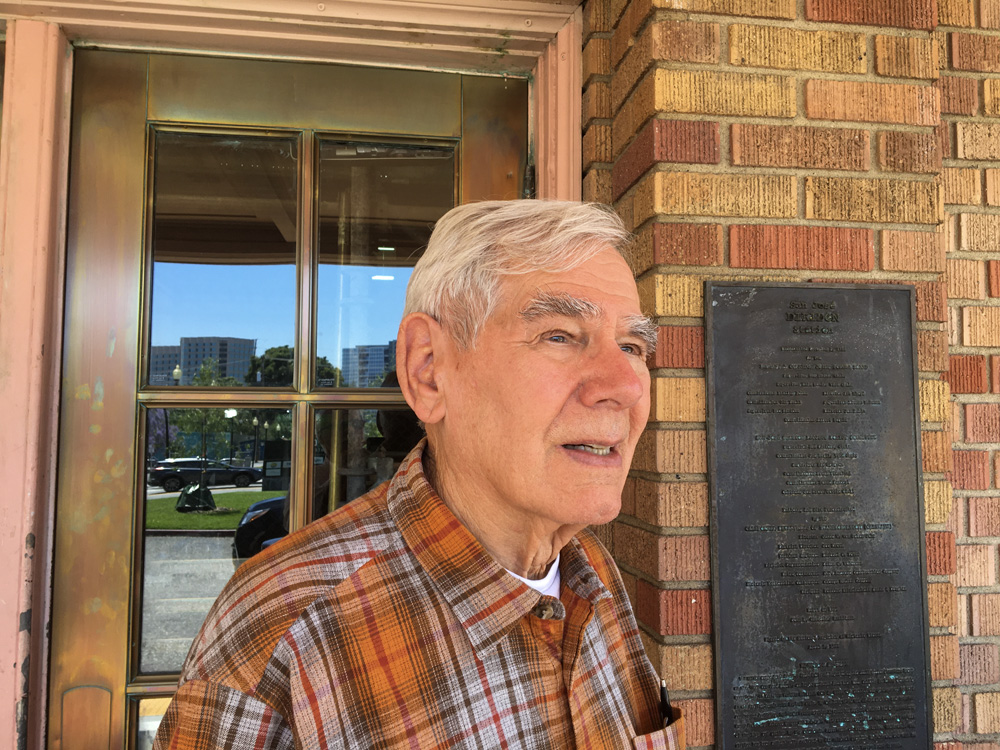

Coincidentally, I’m currently reading Mr. Loving’s 2006 book “The Men Who Loved Trains.” Mr. Loving has a vast knowledge of the turbulent period that gave rise to Amtrak and a lot of other change, and many industry contacts he developed have since been claimed by time. I’m happy he’s still sharing his vast knowledge with us.

Very glad to see Rush Loving’s byline again. He was present at the beginning of many events that have shaped much of today’s railroad. Not too many of Rush’s contemporaries still with us. Hang in there, Rush; your perspective and wisdom are much appreciated.

Congress’ third great mistake was allowing Amtrak to purchase the Northeast Corridor (NEC). Instead the USG should have organized a USDOT agency similar to the St Lawrence Seaway Development Corp. to purchase, operate, and develop the NEC rail line.

very interesting