Them’s the breaks

Late afternoon on Jan. 30, 2007, my conductor and I were called for the SSEALPC — a stack train from Seattle to Logistics Park, Elwood, Ill., a suburb of Chicago. Our train that day was FURX No. 8117 as the lead unit of six, trailing us were 63 loads, zero empties, 5,924 tons and 5,729 feet. These trains were notorious for less than perfectly maintained power and one of the heavier trains without helpers or distributive power to travel east over Steven’s Pass — the BNSF Scenic Subdivision of the Northwest Division.

We started our trip by going on duty at Balmer Yard (ex-Great Northern) north of downtown Seattle and took a crew van to Stacy Street Yard (ex-Northern Pacific) just barely south of downtown. After I inspected the power, we backed onto the train. When the carman completed the air test, we doubled over and made our final brake pipe test. Stacy Street was by this time a stubbed yard, meaning everything departed south. However, there was a wye at Spokane Street, a half mile south from Stacy Street, we would take for our destination of Wenatchee and a crew change. We took the wye to head east. Just as we reached the main line, we got what I called a “WOW” — this is where the power suddenly surges ahead due to a runout. It is not a comfortable feeling. We exchanged looks, I just shrugged, I had no clue what it was.

The trip was going nicely — just rolling along — then at Gold Bar we got another “WOW.” Again, we exchanged looks. I just silently shrugged as I still had no clue of the reason, though I was more concerned this time — the first was at 10 mph, this second at 50 mph. Gold Bar is the start of the climb over the Cascades Mountains.

At Skykomish, we stopped to pick up my road foreman of engines. After our guest was on board and we reached the east end of Skykomish, we started up the 2.2% grade to Scenic and the Cascade Tunnel’s west end. There was fresh snow as we traveled up the hill.

Just after I took the clear (green) signal at West Scenic we got the final “WOW” with a “POP” as the train went into emergency braking.

My conductor started back to walk the train and find the problem, it didn’t take long. We had broken in two just behind the power. At this point the road foreman got up, telling me to stay up front while he went in the back to help.

I was sitting there by myself stewing about what I had done wrong. At the time, a few engineers (including me) were using PalmPilots to help calculate the math on tonnage and horsepower versus grade. Another engineer had written the code, it was a great program. While my conductor was busy tying the train down — about 20 minutes later — I realized I had not heard from the road foreman. I stopped feeling sorry for myself and started to grow concerned about the road foreman. I walked back through the power and, leaning over the platform railing, asked him if he needed help. “Oh yes,” he said, “I could use some help. I’m trying to get this knuckle in, and it won’t lock up.”

The road foreman was using one hand to work the knuckle into place while holding up his pants with the other hand. His belt was holding up the cut lever. I offered to give him a break — no pun intended— while I tried. After few rounds of my own, I noticed the broken knuckle was a grade “E,” not a grade “F” like it should have been. Grade F couplers are stronger and better versions of Grade E. They are made so the parts are not interchangeable.

The broken knuckle was an “E,” according to the road foreman, which should have never happened. Someone somewhere got the wrong knuckle to lock up and it had failed. We had a little chat about it after we got the train back together and pulled up to the east end of Scenic to meet the dog catch crew.

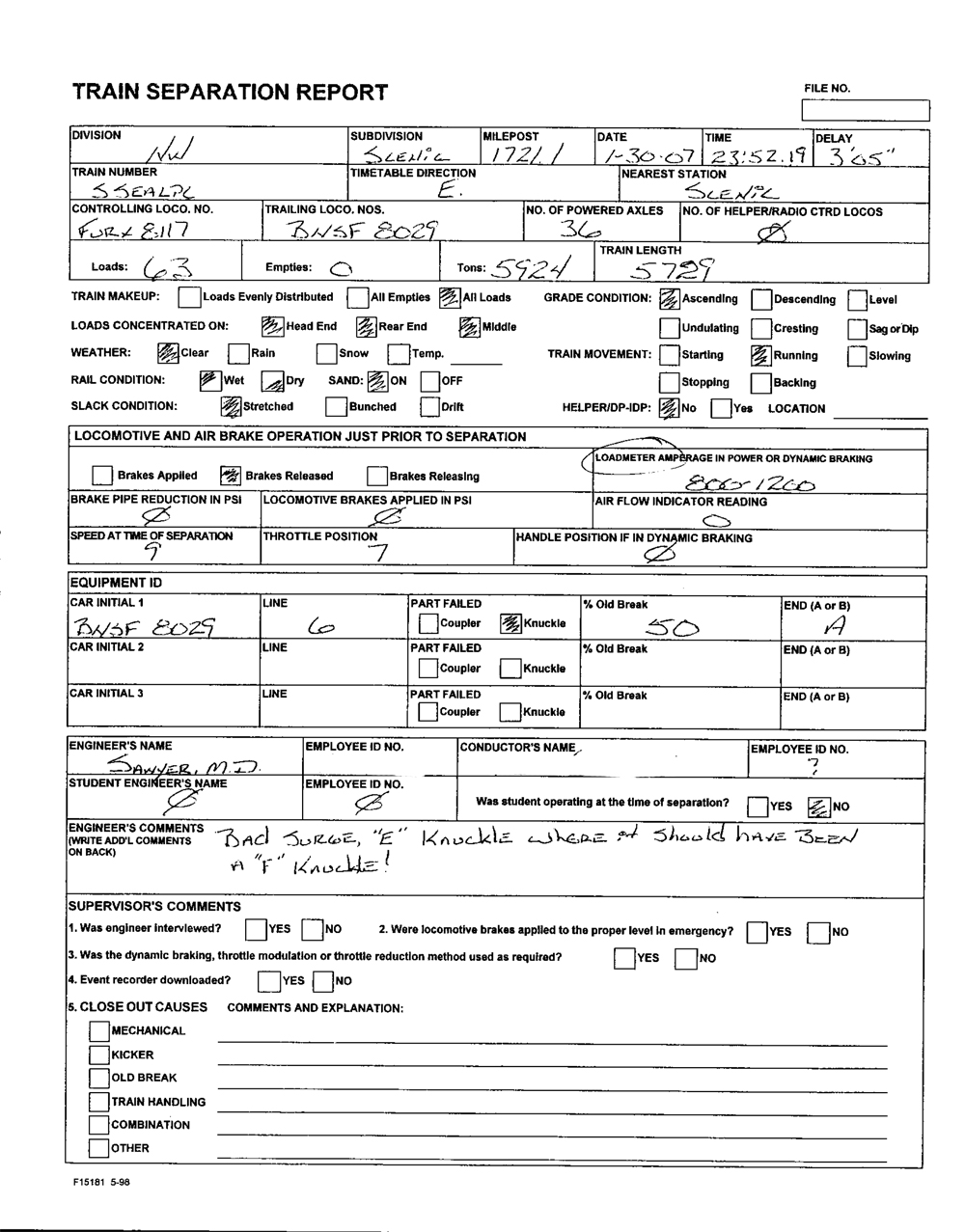

My best guess was that with the wrong grade of knuckle on the last unit it was too much for a knuckle that already had a 50% break — as a knuckle suffers from fatigue over time, a small fracture can start. This fracture will start to rust. In this case, the knuckle was 50% rusted, meaning it was failing before I got it. This would explain why I was getting “WOWS” and, of course, due to the law of railroading, it waited until the most inconvenient place to give up. I never heard anything more about it. I did fill out the proper paperwork. I didn’t even have to mail it, I just handed it over to my road foreman, who had witnessed it all.

Like this column? Read the author’s recent, “An engineer’s life: What the heck are railroad fusees for?”

Good story. This is the kind of thing I like to see, and read, on the Trains web site. Would be interesting to read stories from the MOW guys and others.

A fine story, thanks for sharing, but one question for this Lowcountry SC fellow, “was it snowing”?

It was clear, it HAD snowed, I rememebr a foot of fresh snow.