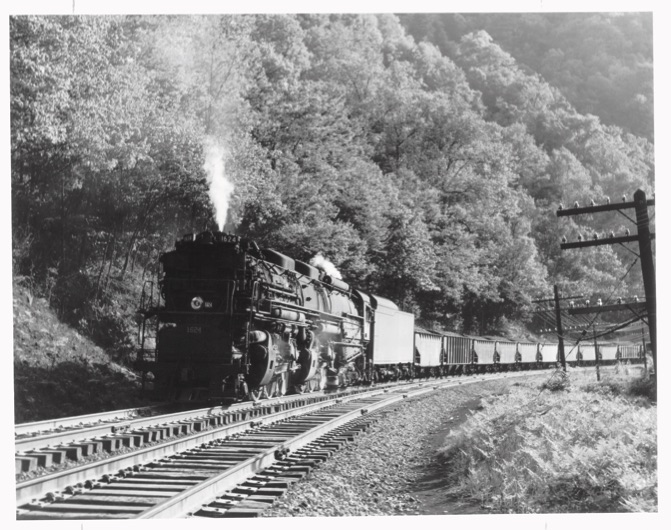

The onset of World War II produced two of railroading’s most impressive “bragging rights” locomotives – Chesapeake & Ohio’s Lima-built 2-6-6-6 and Union Pacific’s Alco Big Boy 4-8-8-4.

Everything about the Big Boy grabbed headlines – from its size (UP called it the “World’s Largest Locomotive,” although C&O’s 2-6-6-6 was heavier and had about the same size boiler) to the appearance of the name “Big Boy” in chalk on the first engine, a happenstance milked heavily in advertising by Alco and UP.

Union Pacific historians are fond of saying that the Big Boy could have produced even more than its 6300 drawbar horsepower (dbhp) if it hadn’t had to use low-quality coal. But that’s difficult to understand, given that during its tests the Big Boy was operated at full capacity and the boiler was fully supplying the demands of the machinery. If higher quality fuel had been used, it might have been able to use less of it. But why design one of the all-time ultimate steam locomotives and handicap it by using inferior fuel? If high quality coal was expensive to come by, why not burn oil?

A curious feature of Big Boy was the use of an exhaust steam injector instead of a more efficient and reliable Worthington or Elesco feedwater heater. Exhaust steam injectors were called “poor man’s feedwater heaters,” but UP was not a poor man. Big Boy historians say that rather than deal with the tricky starting sequence of the exhaust steam injectors, many engine crews avoided their use and ran on the regular injector alone, which defeated the purpose of the application. That seems strange in light of UP’s carefully nurtured reputation for requiring only the best of everything.

Alco and UP also promoted the claim that Big Boy’s machinery was designed for 80-mph operation. But USRA engines of 1919 – the 4-8-2s, specifically – with drivers only an inch larger and counterbalanced with 1919 technology, had been capable of running 80 mph for 22 years. And other than attracting publicity, what was the actual value of running Big Boys at 80 mph? How much of Big Boy’s running time was spent going more than even 65 mph?

What UP needed was a locomotive capable of handling tonnage up the Wahsatch and Sherman grades and then running 60 mph between those summits. With Big Boy the railroad got more speed than it could make use of, and less tonnage-hauling capacity than it should have, given the engine’s weight.

They sure were pretty, though.

The C&O and Lima got similar publicity for their 2-6-6-6. The Allegheny proves that not all Super Power was created equal. It is well documented that the class H-8 2-6-6-6 had been, from the outset, designed to outperform N&W’s class A 2-6-6-4 of 1936. The Advisory Mechanical Committee (AMC) of the C&O and other Van Sweringen roads had more than five years to consider the performance of Seaboard’s 2-6-6-4s of 1935 and UP’s Challengers of 1936 to aid in designing a new high-speed articulated. The AMC knew that C&O would buy anything it recommended and was willing to spend as much of C&O’s money as necessary to accomplish its goal.

N&W’s A had produced 6,300 dbhp in testing, and C&O and Lima people on their own dynamometer car shed tears of joy when that figure was exceeded by the Allegheny to a maximum of 7,498 dbhp. But the first 10 A’s weighed 570,000 pounds compared to the Allegheny’s 778,000 (the heaviest reciprocating steam locomotives ever built). Each A cost $123,448, while C&O paid $230,663 for each of the 10 earliest 2-6-6-6s (this figure is not out of line; UP paid Alco $133,000 each for its 1936 4-6-6-4s, which presumably included a profit for Alco. N&W, of course, didn’t have to cover a profit to its Roanoke Shops). The 2-6-6-6 carried nearly as much weight on its trailer truck as the total engine weight of a Southern class Ks 2-8-0, and N&W’s entire class M 4-8-0 weighed only about three tons more.

So the Allegheny did, indeed, beat the A’s horsepower figure. But for an additional 100 tons of engine weight and an extra $100,000 per engine and tender, shouldn’t it have? You can do the math and form your own conclusion about whether C&O got its money’s worth out of all that additional weight and expense.

The 2-6-6-6 is today considered by many to be the ultimate expression of the Super-Power concept. However, C&O put these engines to work in the mountains, where they seldom if ever got to use all that horsepower, and their 110,200 pounds of starting tractive effort limited the tonnage they could handle; their rating was only 200 tons more than the H7 2-8-8-2 of the 1920s. The 2-6-6-6 fared better hauling tonnage up through Ohio on C&O’s Russell (Ky.)-Toledo run, but because of a car limit imposed by the operating department, Chessie’s T-1 2-10-4s (probably Lima’s finest locomotive) of 1930 could do the same job much more economically.

But what happened to the idea that the engine should be a tool to make as much money as possible for its owner? Was it a sound business decision to design and build such an expensive and heavy locomotive just to outperform another locomotive? Rather than admit a mistake, C&O went on and bought 60 of them.

The wartime president of C&O neighbor Virginian, Frank Beale, came from C&O, where he’d been an operating official on Allegheny Mountain when the 2-6-6-6s came. Beale was highly impressed (motive power must not have been his strong suit). He must have figured that VGN had no mountains east of Roanoke, so the 2-6-6-6 would work just fine. He bought eight more of them, plus five C&Ostyle 2-8-4s for fast freights. For a 35-mph railroad, here were 13 big, heavy, expensive locomotives, each of which developed its maximum drawbar horsepower at better than 40 mph. But, like their C&O counterparts, the fans and historians liked them. The stockholders didn’t have a choice.

This story originally appeared in the September 2004 issue of Trains Magazine.

Dear Mr. James R Black, the H8 did not have “low pressure cylinders”.

I don’t understand why no one is not complaining about Union Pacific. If I interpret correctly, all the

steam engines they have, so called “restored” , have been converted to oil. That is their prerogative, however distasteful, but to not change the engine number when converting to oil like every other railroad or preservation society is dishonest and deceitful, not to mention pushing it around with a repulsive diesel in tow.

I suspect that it is because fuel oil causes many hot spots in the fire box and boiler which shortens engine life. I believe this is the reason they operate it at low throttle .Did you know they have to throw sand in the fire box to give photographers some exhaust smoke to photograph?

PITIFUL.

Please don’t give me the company spin as validation. All the reasons for converting to oil are both insipid and lame.

These arguments aside, I can fine no real reason for UP not changing their engine numbers, or is the addition of an asterisk too costly?

Come clean, Union Pacific, and change the engine number on your resto-mod oil BURNERS and salvage your honor and reputation, if that’s possible at this point.

One factor not discussed in all these discussion is driver diameter. The BB had 68 inch drivers vs Y6 56+57. Taking a tractive effort calculator formula putting 57 inch drivers on a BB would give it a 191,000 tractive figure vs the 135000 using the 68 in drivers. With the exception of the 2666 the final age of steam giant members seem to me designed to work as efficiently for their specific work areas given coal quality, topography and logistics, etc.

Included on this discussion are the impressive stats (to me) for the n&w class A especially vs both the UP 3900 and 2666. There are many old movies of this engine performing heavy coal drag (w Y6’s) to fast freight-passenger service very well. I REALLY like it’s steam whistle.

I humbly have to agree with the less than complimentary comments below regarding the 2666’s high axle weight and weight distribution which severely limited its range and high speed opportunities Lima had to pay C&O millions in damages due to the axle weight issue. Hardly a successful design adding to comparative engine costs and other deficiencies mentioned below. A very heavy price for Lima to pay for horsepower and engine weight bragging rights. I am sure they lost money on the beast.

I believe that the 4000 would of out.preformed the H8 with a better grade of coal.The 4000 had a larger grate area and more super heat.The H8 had low preasure cylinders which gave it the advantage in starting the load but this advantage would of quickly disappeared once the 4000 got going.The H8 had a problem with the axel weigh while the 4000 was a better balanced engine.We will never know for sure because the H8 engines has nothing available for testing.Had the 4000 had a fire box as deep as the H8 I don’t believe we would even have this conversation.

VINCENT SAUNDERS. You said, “And the truth is that at the weigh in of the Allegheny, a few shenanigans were undertaken to make sure it weighed more than a Big Boy.” I don’t know where you get that information, but please read Huddleston’s “Allegheny, Lima’s Finest”. The issues at the scale house in Lima were that the H8 was too heavy, and Lima tried to hide this fact.

The N&W Y6 was certainly an impressive locomotive, but it was not capable of doing the same type of work as a UP 4000. The Y really excelled hauling dead freight (coal and other non-time-critical commodities) up steep grades. It was efficient at this job and was capable of high tonnage ratings. However, a comparison of drawbar pull curves of the Y6 and the UP 4000 shows that the Y’s large starting tractive effort advantage (made possible by simple operation of the low pressure cylinders) is gone once its speed reaches 8 miles per hour. The UP 4000 has a slight edge in drawbar pull up through 20 mph, but at 30 it is outpulling the Y by 12% and at 40 mph, it is producing a whopping 41% higher drawbar pull.

So, as long as you’re content to limit your train speeds to 30 mph, the compound Y is a great choice. But if you’re hauling perishables or otherwise time-sensitive freight, you also need a locomotive that can run 60 mph mile after mile without pounding itself to death. With 57″ drivers and front cylinders that were 39″ in diameter, the Y couldn’t do that.

The best thing about the UP, C&O and N&W super power steam is it gives us all something to chew on ’til we are dust w/o a definitive answer on who was best 🙂 Points about tractive power comparing UP Big Boy’s 135k lbs at 0-35 mph to C&O Allegheny’s 110k lbs at 0-45 MPH, and that all manifest freights ran 40-50 mph tops, are key. In fact, BB was pulling at just 12-15 mph up its longest grades, same as trains back east, with ruling grades conquered being fairly equal, Rockies v Smokies. But the debate requires inclusion of the Y6b. N&W Y6’s (and later after re-fitting all Y4’s and Y5’s with the same valving to run simple as well as compound) out-pulled BB’s 152k @ 0-25 mph (with the simpling valve open) vs. 135k lbs @ 0-35 mph. Considering Y’s weighed only 582k-611k lbs compared to BB @ 762k-772k, those numbers are incredible.

Although BB’s average operating speeds were something on the order of 10-15 mph faster on the flats than Y’s they had to stop more often for fuel & water due to the efficiency loss of running simple vs variable compound steaming of the Y. This wound up mostly negating bottom line benefits of the better speeds. Bottom line, the late Y’s averaged an impressive 89,000 gross ton miles per train hour. When N&W needed passengers and freight delivered ASAP, they used the A which, although it weighed 10k lbs less than the Y and 200k lbs less than the BB, pulled 125k lbs drawbar, at operating speeds up to 70 mph. (BB never ran faster than 72 mph on its best record run ever, and operated under typical loads at 50mph.)

25 Big Boys all ran a million miles each, or ~25,000,000 miles. Although I am not aware of any N&W boasts of a million miles per loco, 101 Y6’s reportedly averaged 6000 miles/month from 1942 to 1957, (last ones were retired 1959) which works out to (4x more) 108,000,000 miles, over a million miles per unit.

N&W ran an A from 1987 to 1994, and I rail fanned it since I lived only two miles from Alexandria Station in VA. Too bad they decided not to continue to maintain and operate No. 1218 after that. Although I am primarily an Eastern RR fan (I think this is determined for most of us largely by where we grew up), I have collected HO models of all the best articulateds including the cab forward, Big Boy, and Challenger alongside the Yellowstone, Allegheny, Chesapeake, Class A, and 2-6-6-2. Love ’em all.

I have visited the both of the two remaining Allegheny’s on numerous occasions, the #1218 2-6-6-4, the #1256 2-8-8-2, and No. 4004 in Cheyenne; and plan to be present for the running of Big Boy #4014. Despite not actually besting the Eastern articulated locos on any given point of contention (other than overall length), Big Boy is, and always will be, the “Big Boy”. Ya cain’t argue with that. Big Boy vs Allegheny goes to Big Boy, hands down.

As to king, it is clearly the Y6b. Without a doubt, that single loco type/class/model pulled harder, went plenty fast enough to fill out the ton miles per train hour dance card, and obviously made more money for it’s owners than any other. Folks, when you talk about who’s king of the rails, you are discussing gold & silver, plain & simple. Y class had hundreds more units built, lasted twice as many years in service, came before and was retired after, and accumulated at least 6 times as many miles in service as Big boy.

See ya in 2019 for the 4014 coming out party!!!

Apples and oranges……….The big boy had two additional drive axles which makes the comparison BS. And while Ed King may like eastern steam power(as I do) his comparisons are fact, not fiction. And Mr. Hildebrandt I couldn’t agree more; I’ll take any Y-6 class engine over that UP junker any day. And Mr. Lehtola, you bet, DM&IR and NP’s Yellowstones were incredible engines, too bad the money isn’t there to get the Yellowstone running again. It has been indoors so it may not be in too bad of shape. The Allegheny is best judged against another 12-coupled engine, the closest would be the A class. And Mr. Nation, you are a nitwit. That’s all, folks.

Locomotives are just tools. Their success depends on humans utilization of them. And utilization is dictated by the circumstances of operating environments. Think, for example, of the Berkshires of similar design that the C&O associated roads utilized. Were the Nickel Plate engines better than the C&O’s? They were by history better because of the environment of their operating circumstances and their utilization, e.g., the N&W-like lubritoriums. Otherwise the arguments have very little basis except in the rare circumstances where engines were tested under similar conditions.

When you consider weight, tractive effort, hp, fuel economy, simple/compound operation, and the ability to run 50 mph, nothing, I mean nothing, beats the N&W’s Y6a’s and b’s! Greatest articulated loco’s ever built!

Ed, your southern bias is showing. Ask 100 people who would know what the best and finest articulated of all time was and 90 of them will say UP’s Big Boy. That’s not a condemnation of the Allegeheny, just a fact. And the truth is that at the weigh in of the Allegheny, a few shenanigans were undertaken to make sure it weighed more than a Big Boy. In everyday assignment, the Big Boy was the heavier and more successful engine if for no other reaon than it didn’t have to waste its horsepower in all those curvy, mountainous drags of the Piedmont. UP only had to hook on mile long trains to her and let her rip and rip they did, and in 2019 they will again.

Oh Ed, one thing we both agree; They really are pretty machines!

Don’t see a reference to the 2-8-8-4 Yellowstone of DM&IR game.

While some might argue that that the Big Boys could produce more horsepower if they used a better grade of coal, that’s not the point. They were designed to burn what the UP was using at the time for all its locomotives. It was what was most readily available for them. They were claimed to be balanced for 80 mph, but typical operating speeds were more like 40-45 mph. I suspect that they produced their maximum horsepower at that speed, maximum tractive effort of 135,375 lbs. was at 35mph. By-the-way that’s 25,000 lbs. more than the Alleghenys’ 110,200 lbs.

All this talk about freights going 60mph in those days is bullshit. Some special expedited schedules may have gone that fast, but not regular manifests. For instance, well into the 30s Espee had a maximum speed for freights of 35 mph.

Look at the service records of all of them. No Big Boy even in the short amount of time they were in service ran less than 1 million miles. I have yet to see any records that state any 2-6-6-6 made it to that milestone before being retired or scrapped.

Ed King is a die-hard eastern railroad advocate to the bitter end. Leave it to a C&ONW man to argue that the Allegheny was a better engine than the Big Boy. Nearly every other rail historian, however, agrees that the 25 Big Boys were the ultimate expression of the high pressure single articulated steam engine anywhere in the world. Built for a purpose which they performed admirably and usually without help, they hauled mile long manifest trains over 9500 Foot Sherman Hill and west through the Wasatch Mountains of Wyoming and Utah to their terminus in Ogden, the Crossroad of the West. They were both great locomotives but the operational evidence suggests that Big Boy was the superior locomotive and the un-doctored successful king heavy weight of all the final beasts of steam. Of course by 2019 one will again be in operation and then all the naysayers can see for them-selves what Big Boy was truly all about, coal or oil powered.