California’s high-speed rail

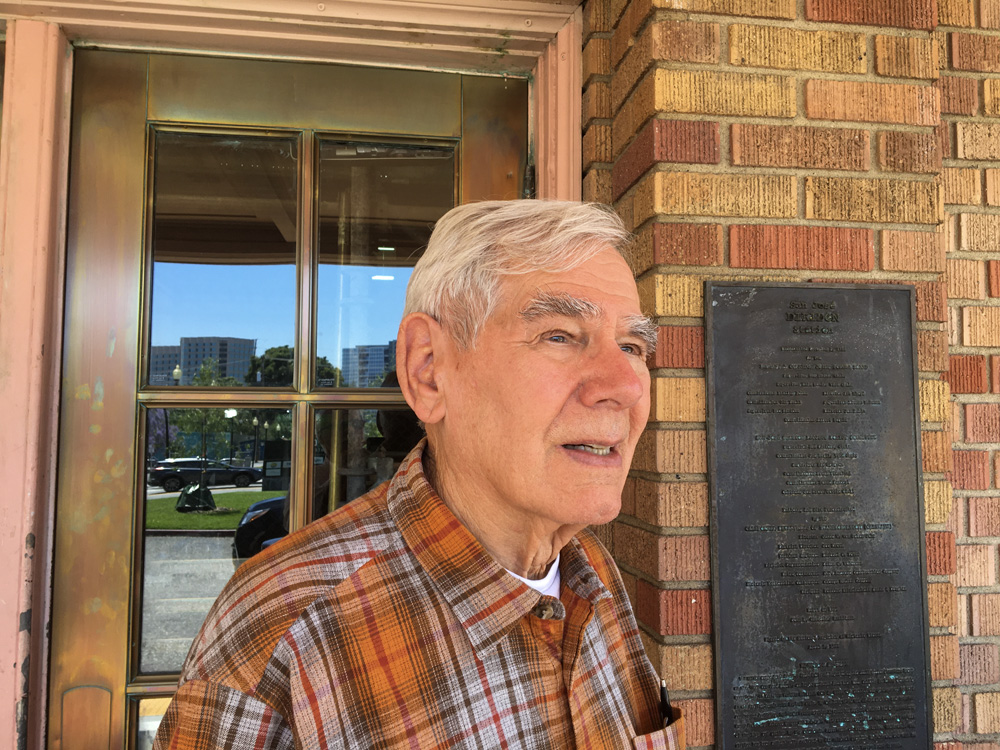

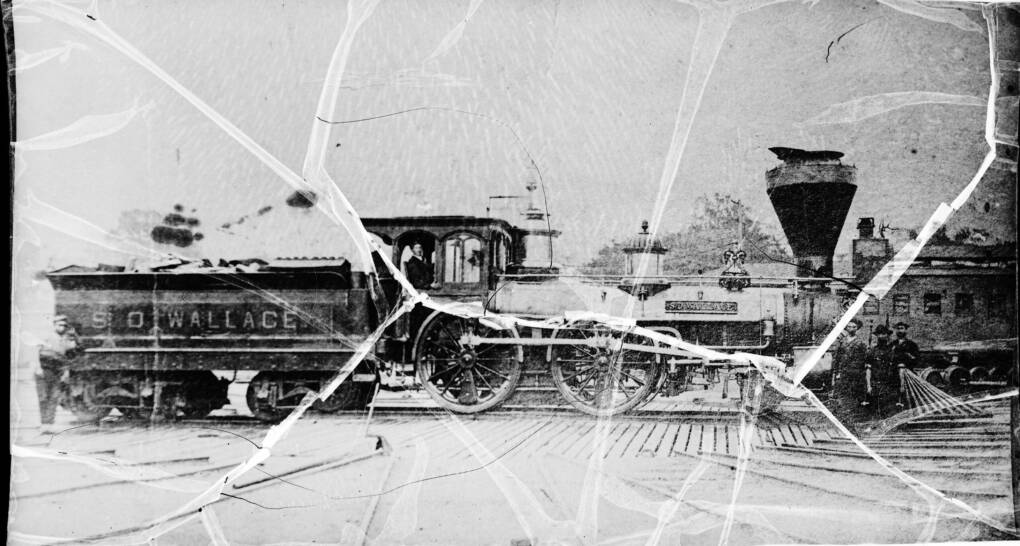

Rod Diridon Sr., 85, a crusader for high speed rail, grew up in the small Northern California town of Dunsmuir. There, he worked for the Southern Pacific during summers and vacations when he was a college student, starting in the late 1950s. The steam era was ending, but steam-era technology was still present.

He remembers, for example, watching for hotboxes on cars equipped with the friction bearings that were common at the time. “Every time we stopped, the swing brakeman — and I was the youngest guy so I often was a swing brakeman — would have to walk the train to look at all of the journal boxes to make sure they weren’t glowing red or smoking,” he said. “In my time, I found half a dozen of those that if they hadn’t been set out at the next siding, they would’ve maybe caused a train wreck.”

After college and combat tours as a Navy officer during the Vietnam War, he moved to the city of Santa Clara in California’s Silicon Valley, where voters elected him to the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors for 20 years starting in 1974. He became an expert on transit and high speed rail. His work was so influential that in 1994, the county renamed the former SP station in San Jose for him.

His career includes many transit-related highlights, including stints as the first executive director of the Mineta Transportation Institute in San Jose, and chair of the California High-Speed Rail Authority board. He is currently co-chair of the U.S. High Speed Rail Coalition. Earlier in his career he worked for Lockheed Corp., and in 1969 he founded the Diridon Research Corp. (later Decision Research Institute), which he sold in 1977.

In summer 2024 we talked with Diridon at his home in Santa Clara about why he is so committed to high speed rail, how he and others persuaded voters to rebuild rail transit in Silicon Valley, the role he sees for Amtrak if it improves its reputation as an operator, and telling his dad Claude Diridon, a longtime SP brakeman in Dunsmuir who was too ill to travel in 1994, about the station renaming ceremony.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Trains: You were a brakeman and fireman for Southern Pacific in Dunsmuir, to help pay for college. Did you enjoy the work?

Rod Diridon: “Enjoy” is a relative term. I needed the money to go to college. I valued the experience, but I didn’t realize I was enjoying it so much as later when I looked back at those experiences and realized how important they were.

![]() I would think your experience working on a railroad would set you apart from people who see rail travel more as a concept or a cause rather than an industry.

I would think your experience working on a railroad would set you apart from people who see rail travel more as a concept or a cause rather than an industry.

I certainly have an understanding of how a railroad works that most people don’t.

But the tracks for high speed rail are built completely differently than for normal 79-mph U.S. rail. They’re managed very differently. When you have trains going 235 mph, as with China now, running 5 minutes apart, you can’t make errors. The construction and the type of train you’re operating, as well as the complicated process of dispatching and managing that kind of a system, all has to be designed into whatever you’re building.

![]() California’s high speed rail project has secured environmental clearances to build its route from San Francisco to Los Angeles. But the estimated cost has grown way past the initial projections. Work is taking years longer than planned. There’s no clear source of money to finish it. The construction so far is in California’s Central Valley, the part of the route with the fewest people. Do you really think the project will get built?

California’s high speed rail project has secured environmental clearances to build its route from San Francisco to Los Angeles. But the estimated cost has grown way past the initial projections. Work is taking years longer than planned. There’s no clear source of money to finish it. The construction so far is in California’s Central Valley, the part of the route with the fewest people. Do you really think the project will get built?

I’m sure the whole thing will be built. Once the country sees our 171-mile section between Merced and Bakersfield, which is a rapidly growing area, in operation, everybody’s going to want one. Already the demand for high speed rail gets up in the 70s percentage approval range when you survey voters in the nation asking, “Would you like high speed rail?”

Will the public want it regardless of the cost?

It’s a high cost. The cost of the alternatives and climate change is much greater.

Eighteen other countries have high-speed rail systems. Nearly twice as many are developing one. China has 26,000 miles of 235-mph trains, and they’re beating our behind environmentally and economically because they move their products and people much more efficiently and sustainably than we do.

It’s never going to be less expensive to build than right now, because the real increased cost is construction inflation. In the United States, it has been 5% and recently as high as 15% per year. If you compound that, you double the price every 5 to 7 years. That’s what’s happened to us. The last time we had a projection was to prepare for the 2008 California bond measure adopted by the people of the state — at that time, about $33 billion. That amount has more than tripled.

They’ve done everything in the world to modify the project to make it less expensive. The cost of construction goes way up with delays.

Britain is extending its high-speed rail system north from London to Birmingham. It’s over two times our costs per mile. They’re going ahead because even at that price, it’s less expensive than building another couple of lanes on your freeways or building more runways on your airports, and then requiring people to use cars and airplanes, which are overcrowded and terrible polluters.

Climate change is real, and it’s going to become more so. Recent polls show that climate change is the driving issue for young people. High speed rail replaces short-hop airlines, which are the most polluting form of transportation in carbon per seat-mile.

![]() Where will the money to complete California’s high speed rail come from?

Where will the money to complete California’s high speed rail come from?

We’ll have to meet the demands of mobility in the next 50 years. Projections indicate that we can do that with a high speed rail system for something in the neighborhood of $100 billion each for the construction project, maybe $120 billion maximum, if we build now. If we were to build two more lanes on the freeways up and down the state, and another runway on airports up and down the state, the expense would be multiple times that cost.

But there’s no land to build another lane on freeways coming into and out of metropolitan areas, where the congestion is. And they’re up against sound walls all over the place, so you can’t solve your transportation problems by expanding highways and airports, even if you wanted to pay that extra cost.

We have no choice.

![]() So in other words, whatever money you’d use to build those runways and lanes, use that money to build high speed rail instead?

So in other words, whatever money you’d use to build those runways and lanes, use that money to build high speed rail instead?

It’s got to come from someplace. Part will come from gas taxes. That will dwindle as people shift to electric vehicles. There must be a new mileage tax. Oregon is testing it. It’s been studied by the Mineta Institute and others, and they conclude that a mileage fee is fair. All you do is to record your mileage each year when you get your registration at the Department of Motor Vehicles, and pay for the miles traveled.

![]() Like a car rental, when you’re paying for mileage?

Like a car rental, when you’re paying for mileage?

Yes. And you have some multiplier per mile. Probably less than the gas tax we currently pay. That would be your bill for the transportation system for the state, as part of your DMV expense. You don’t have to create a new mechanism. It’s all there. Same thing for trucks, only they ought to pay a lot more than they’re paying because they cause more wear and tear on the highways.

![]() You’ve said that once the Central Valley high speed rail segment connects to the San Francisco Bay Area —

You’ve said that once the Central Valley high speed rail segment connects to the San Francisco Bay Area —

It can become profitable on operations.

![]() Because it’ll let people live remotely and still participate economically in Silicon Valley?

Because it’ll let people live remotely and still participate economically in Silicon Valley?

Normally young families create wealth by buying a house. You’re not paying rent for somebody else’s equity. You own that yourself. Even the relatively highly paid tech workers can’t do that in Silicon Valley any more. Housing costs there are very high.

The region is still recruiting, though — the best and brightest from all over the world — to come here and create the next widget and become the next billionaire. The kids are living further and further away in order to reach affordable housing. Now, housing in the Central Valley is much more affordable, but then you’re stuck with a commute, you leave before the kids wake up. There’s a lot of wear and tear on your car. It’s typically gas-powered. You’re on a dangerous road coming into Silicon Valley. Nearly 200,000 trips per direction per day are doing that. That’s a lot more than 200,000 people. They’re getting here frazzled after 21/2, 3 hours of commute. They try to do a day’s work competing with the world in terms of genius.

And they do it again the next day. That’s not a civil life.

The trip on high speed rail from Fresno to the downtown San Jose Diridon station will be less than 60 minutes. You ride comfortably, have breakfast, start work early online, or catch a nap. When you get here, it’s another 10 to 20 minutes on commuter shuttles that greet people at the station. Then they reverse that in the evening.

That’s the difference that will capture virtually every trip from the Central Valley into Santa Clara County. At that volume, that system will be profitable on operations.

![]() You’ve talked about other U.S. locations for high speed rail, such as Chicago, Texas, and the Pacific Northwest. What makes those places favorable?

You’ve talked about other U.S. locations for high speed rail, such as Chicago, Texas, and the Pacific Northwest. What makes those places favorable?

First, they’re focal points of commerce. Chicago is probably one of the greatest commercial centers in the world. Seattle, Portland, and Vancouver are emerging as very large, strong commercial areas. Silicon Valley speaks for itself. The Los Angeles Basin speaks for itself. The Texas Triangle — Dallas, Houston, and Austin — are rapidly evolving commercial centers. Southern Georgia, Georgia to South Carolina, North Carolina, is a corridor. Atlanta is exploding in commercial capacity. Florida is very dynamic.

Each needs more transportation capacity. Several have very serious pollution problems. High speed rail solves both problems. You compete very favorably against air travel up to about 800 miles, depending on the route.

![]() Brightline West is building a high-speed rail line between Rancho Cucamonga near Los Angeles, and Las Vegas. It has several advantages: private builder, private investors for $9 billion of the cost, use of an existing right of away along Interstate 15. Is Brightline West a better model for future high-speed projects, more than the publicly funded model?

Brightline West is building a high-speed rail line between Rancho Cucamonga near Los Angeles, and Las Vegas. It has several advantages: private builder, private investors for $9 billion of the cost, use of an existing right of away along Interstate 15. Is Brightline West a better model for future high-speed projects, more than the publicly funded model?

If you have the same conditions.

![]() How similar do those conditions have to be for it to work?

How similar do those conditions have to be for it to work?

They’re very rare. You’re coming out of Las Vegas and into the high desert, and you’ve got a virtually straight freeway running through the desert. The state has given them access to that freeway right-of-way. When you have those conditions, use them. That’s a very inexpensive way to build a high-speed rail system.

![]() Like many places, Santa Clara County abandoned its electric rail transit in the first half of the 20th century. In the 1970s, you and others helped persuade the public to re-install a rail transit system in the area. You credit several factors — an influential article criticizing Santa Clara Valley and San Jose as polluted, crowded and exceptionally poorly planned; a change in regional politics as the valley evolved from ranching to technology; increased public attention to the environment; you even still had some rights-of-way or access to places where the rails maybe were gone —

Like many places, Santa Clara County abandoned its electric rail transit in the first half of the 20th century. In the 1970s, you and others helped persuade the public to re-install a rail transit system in the area. You credit several factors — an influential article criticizing Santa Clara Valley and San Jose as polluted, crowded and exceptionally poorly planned; a change in regional politics as the valley evolved from ranching to technology; increased public attention to the environment; you even still had some rights-of-way or access to places where the rails maybe were gone —

Not many places, but in some, yes.

![]() And this part seems key: You built a transit master plan that stayed close to the voters.

And this part seems key: You built a transit master plan that stayed close to the voters.

The way we’ve always put it is that the voters built the plan. We hired first-rate engineers to design a system. The engineers brought alternatives, and the voters reviewed it and chose the alternatives they wanted. Voters approved the master plan in 1976, along with a permanent half-cent sales tax for transit. The first in the state.

That master plan said we had to redo it every 4 years, with public hearings, to adjust the plan and have it back to the voters for re-approval. In the reviews, if the public came up with good ideas, the ideas went into the plan. If an idea wasn’t good, we had the responsibility of explaining why. The policymakers, when those meetings occurred in their districts, were at the hearings. It added a lot to your work, but it also gave you an opportunity of talking to your constituents a whole lot more.

![]() Can your scenario apply in areas with different political points of view?

Can your scenario apply in areas with different political points of view?

If you set the system up for engineers to identify all the alternatives, and you take those alternatives to your public with a description of what happens in the longer term with each alternative, then most publics, conservative or liberal, will choose an alternative which is affordable and gives you a better future. And that has to be mass transportation in most of our major metropolitan areas, even when they’re conservative. Remember, though, that most of the heavily populated metropolitan areas, even in Texas, are not conservative.

![]() What’s your take on Amtrak? How would you make it more meaningful to more people?

What’s your take on Amtrak? How would you make it more meaningful to more people?

I’ll give you this answer with some ambivalence. I wish Amtrak was not committed to traditional rail technology. They’re gradually breaking that. They’ve even developed a high-speed rail department. To be relevant in the future, they’ve got to commit to building high speed rail throughout the nation. They should work with the Brightline and California high-speed rail contractors to learn how it’s built and operated, and how to integrate it with their traditional rail systems.

Amtrak ought to work with Brightline to eventually take over those systems because at some point, the Brightline lines being built now — the cash cows — when you extend those into less populated areas, eventually they will lose money on operations and require a subsidy,

![]() At which point, the service becomes more of a public good?

At which point, the service becomes more of a public good?

That’s right. If we’re going to have a national network that serves not just major metropolitan areas but also some smaller communities, then Amtrak has to become involved, because they will need to integrate the system and be a source of funding operating subsidies.

![]() So, thinking way out in the future, do you see Amtrak as a high-speed rail operator?

So, thinking way out in the future, do you see Amtrak as a high-speed rail operator?

In ideal situations, Amtrak should run all of the interregional rail systems in the nation. I don’t think they’re ready to do that. If they tried to do it now, they would be repulsed, dramatically, by local jurisdictions, because they haven’t yet earned a reputation as good rail operators. Ideally, you want one rail operator for the nation, and you want to fund that operator liberally so they can compete against the airlines and any other form of transportation. And reduce carbon pollution and highway congestion.

Now, realizing that ideal isn’t likely to happen, not in my lifetime and probably not yours either, then we need to have Amtrak beginning to earn the right to be the nation’s rail operator again, by doing a lot better job with their Amtrak responsibilities so that you don’t have to expect to be hours and hours late on an inter-regional train on a routine basis. They ought to be able to do that now, because the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law gave them a lot of money. They’ve got to begin delivering service that would be competitive with the national train service in Germany or France or Britain.

![]() European passenger rail services are a mix. Some high speed rail, some local. Is that what you envision for Amtrak?

European passenger rail services are a mix. Some high speed rail, some local. Is that what you envision for Amtrak?

Yes. Amtrak should take on the responsibility for long-distance interconnectivity. Long-distance typically is beyond state borders. It should be high speed rail where it makes sense, up to 800 miles, the distance where high speed rail is clearly more convenient than short-hop airlines.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres has warnings about climate change. By the early 2030s, we’ll know whether we have a future on Earth. If we don’t convert from the combustion of fossil fuels to create energy, then we are not going to have a future. In less than 10 years, my four grandbabies will be young adults. They’ll say, “Papa, when you still had time, did you do everything you could do to stop climate change?” I’m going to look at them and say “yes.” I guess I have to ask, what will you say to yours?

![]() San Jose’s main train station, which opened in 1935, was renamed for you 30 years ago because of your influence shaping rail transit in the area. Your dad Claude Diridon was a brakeman for the SP in Dunsmuir. What would he think about your name on the station?

San Jose’s main train station, which opened in 1935, was renamed for you 30 years ago because of your influence shaping rail transit in the area. Your dad Claude Diridon was a brakeman for the SP in Dunsmuir. What would he think about your name on the station?

Well, that’s a sad story. My dad was in the hospital when they decided to name the station after me. When I told him, he says, “Wow, that’s really interesting.” He was always understated. We were going to bring him down to the dedication ceremony, Dec. 8, 1994. I was going to introduce him as the real big-dog railroader. The night before the dedication, he got out of his hospital bed, fell, and broke his hip. The doctor had to operate and set the hip and all those things. And he couldn’t come to the event.

As soon as the ceremony ended, my son and I got up to Mount Shasta, where he was in the hospital, as fast as I could. I got a speeding ticket on the way. We went into his room. He was still barely cognizant. I held up the poster describing the day’s events, and he smiled, and he nodded, and half an hour later he was dead.

![]() He must have been proud of you.

He must have been proud of you.

I think he was. He’s a tough old bugger. He didn’t show love or pride or those kinds of emotions very much. I think he was.

![]() You came a long way from your start in Dunsmuir as a brakeman, to having your name on a busy train station, one of the biggest in the western U.S., and poised to get busier.

You came a long way from your start in Dunsmuir as a brakeman, to having your name on a busy train station, one of the biggest in the western U.S., and poised to get busier.

Raggedy-ass railroad kid. That’s what they used to call us, because our jeans were always frayed in the behind.

Now you’re a raggedy-ass railroad kid with your name on a station in San Jose. That’s a good legacy.

I think about that. I try not to think about it too often because I fear becoming complacent. It’s a very nice thing to have happen. I’ve been very lucky to be recognized in that way. I’ve got to spend every minute of the rest of my life earning that recognition. That’s why I’m co-chair of the U.S. High Speed Rail Coalition and I’m giving speeches all over the world by Zoom. I used to take airlines around the world. I’m trying hard to merit that confidence. The rest of my life will be a fight for high speed rail, and against climate change.

— Updated Jan. 3 at 4:05 p.m. to restore missing first paragraph.

This is total garbage. High speed passenger rail? Railroads abandoned passenger rail in the early 70’s because it was a money-loser and unsustainable without massive government money and losses. A visionary? Let me see the cost-benefit analysis for this gross over-budget money loser. Another complete waste of money at the altar of “climate change”. Change “visionary” to “delusional” and the article makes sense.