Crash at Crush history

“Crash at Crush” turns up thousands of Google search results. Many of these point to the fateful publicity stunt that killed three people and injured more in 1896. What was William Crush thinking the day he thought up a staged train wreck in Texas? Here was a quiet man who went on to complete 57 years with the railroad as a passenger agent. What inspired this particular stunt?

Perhaps it was the success of a staged train wreck in Ohio for the Columbus & Hocking Valley Railroad or the prompting of a friend who might benefit from this escapade? There was no doubt that the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad, better known as the Katy, could use some good publicity. People were getting used to railroads; they were no longer a modern marvel. Bad press from wrecks further dampened the public’s enthusiasm. Whatever the motivation, the Katy’s board loved the idea.

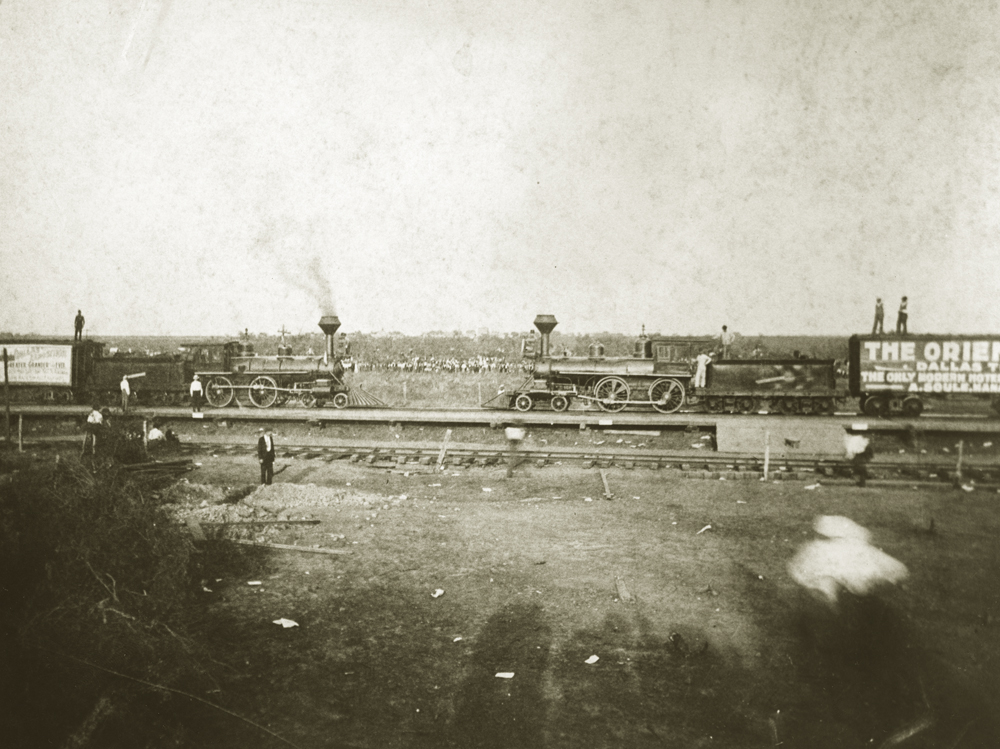

Crush train crash locomotives

To do this, the railroad took two 35-ton 4-4-0s built in 1870 and shined them up for a promotional tour. No. 999 took green paint and red accents, while No. 1001 glistened red with green highlights. Seven cars with large signs for sponsors followed, including P.T. Barnum’s circus and the Orient Hotel in Dallas.

The engines toured towns along the Katy with promoters handing out leaflets. Newspapers carried word of the event across the country. Before it was done, people were making arrangements to be there from as far away as New York City.

The crews were made up of Frank Barnes and E. Stanton on No. 999, and Charles Cain and S.W. Dickerson on No. 1001. Katy Master Mechanic McElvary oversaw both engines. He reassured everyone that it would be a safe event and the boilers would not explode at the speed anticipated. For a year, the crews toured and promoted the event at Crush, Texas, named for William Crush, who organized the festivities set for Sept. 15, 1896.

Train crash preparation

The site was a natural amphitheater about 15 miles north of Waco. Track crews laid a spur off the main line at Waco and extended the rails for 4 miles, so the operation would be safely away from regular train traffic. Workers built a depot with a 2,100-foot platform so that 10 trains could unload passengers simultaneously, plus a shop and two telegraph stations.

For weeks, crews ran the engines up and down the 4 miles of track to see where the exact point of impact would be. From the place they decided on, workers built a grandstand 200 yards away for VIPs, and a press box 100 yards away for photographers. Among the photographers was an assistant to Thomas Edison, who was filming events around the country with his new motion picture camera to show on his vitascope screens. Additionally, there was a bandstand, and three stands for politicians to entertain the crowds with oratory.

William Crush arranged to borrow a tent from the Bailey circus, and the superintendent of the Katy eating house service was put in charge of sandwiches to be sold there. To keep the crowds in good shape, he arranged for eight tank cars full of free water and ice for the public. In fact, the whole event was free. The only cost was the tickets to get there: a $2 round trip for Texas residents.

Medicine shows, gaming stands, lemonade stands, and soda stands were allowed in the carnival setting. Liquor was not sold, as promoters anticipated that everyone would bring their own. A jail was set up in case of problems.

Day of the train crash at Crush

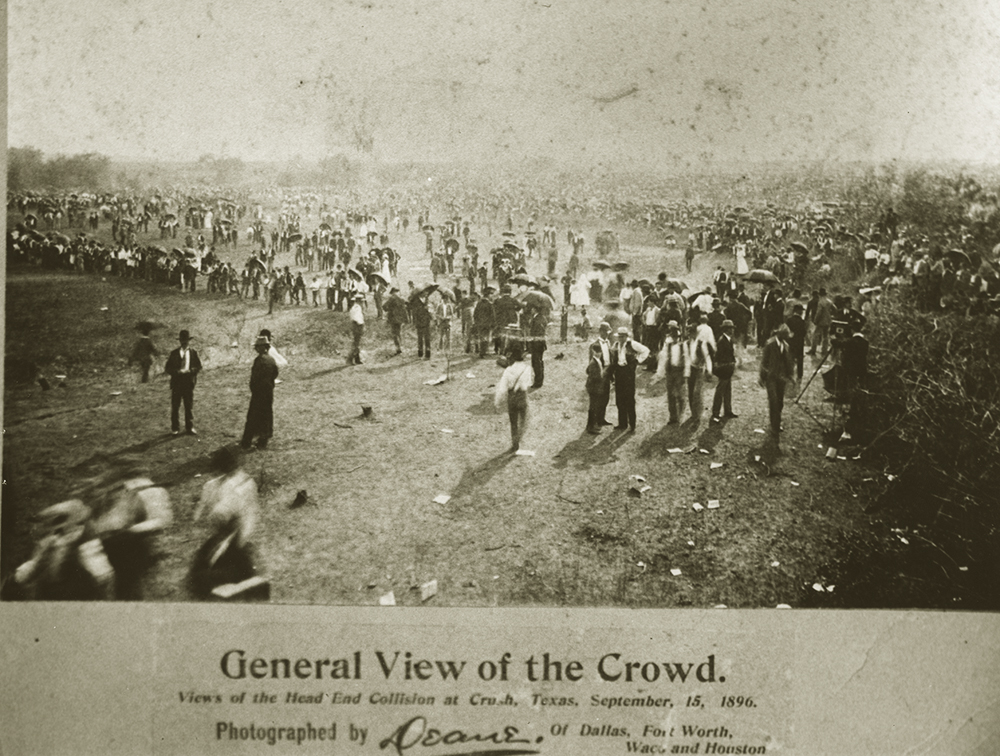

When the big day came, people from all over Texas showed up. Most arrived by one of the 33 trains that arrived about every 12 minutes. Others came by horse and wagon.

As the afternoon wore on, temperatures rose, the crowd grew restless, and organizers pushed back the time of the crash by an hour to accommodate a late-running train. They also moved the crowd back, although some children managed to climb into a tree near the tracks.

Finally, with everyone in place, the two engines met nose to nose, and Crush, riding on a white horse, posed for pictures with the crews. Then the engines backed away to a point 1 mile from the designated collision point. With the engines ready to go, Crush dropped his white hat, the engineers opened and set the throttles, then jumped from the cabs of the runaway trains. A string of cherry bombs exploded, the crowd roared, and then came the smashing sound of metal colliding.

Boiler explosion at Crush

The engines flattened each other and six cars behind them. The crowd fell silent, and then — contrary to predictions — the boilers exploded, sending wreckage flying into the air. A driving wheel went spinning more than 2,500 feet, landing in the crowd.

Miraculously, only three people were killed out of an estimated 50,000 spectators: a boy who had climbed into the tree near the tracks, a man standing between two women who were both unharmed, and another woman. Six more were injured and required medical attention. The only other injuries were burned fingers as people hungrily picked up a piece of fiery history to take home with them.

The railroad paid a settlement to the families of the three killed and to the injured, who also received lifetime passes on the railroad. Officials fired William Crush because of the fatalities, but then hired him back the next day. In spite of the tragic loss of life, the event was considered a great success: The Katy Railroad had gotten the publicity it wanted. Government officials, however, were horrified, and the state of Texas banned staged train wrecks.

I love trains, but bemoaning the destruction of two steam engines is ridiculous!

Three human lives lost far out weighs anything else.

Personally, operating a diesel locomotive is far superior to any smoky, hot, and dusty steam engine.

What many people don’t know about this event is that the great, world-famous Ragtime composer, Scott Joplin, wrote a piece entitled “The Great Crush Collision March”

Some Ragtime and Joplin enthusiasts have theorized that Joplin could’ve been at the event although that is somewhat speculative and can almost certainly never be proven or disproven.

Technically, “The Great Crush Collision” is not a true rag but rather an unsyncopated piece for the piano. Nevertheless it is an interesting piece of music that was written during Joplin’s formative years.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tp_k5Li3C-Y

The Crash at Crush was pure barbarism with the destruction of two perfectly fine 4-4-0 steam locomotives being destroyed in a staged collision.

Officials were right to fire Mr William Crush before rehiring him apparently at the request of a ‘bleeding heart’.

The two locomotives would have become great collectibles had they been saved and restored through this day.