Mind-blowing East Broad Top facts

Tucked deep in the Allegheny Mountains, between Altoona and Harrisburg, is Rockhill, Pa. Today, Rockhill is home to a railroad time capsule called the East Broad Top Railroad, arguably one of the more famous and best-preserved U.S. narrow gauge lines. Built between 1872 and 1874, the EBT mostly lugged coal from the local mines to an interchange with the Pennsylvania Railroad at Mount Union, Pa. On April 6, 1956, freight operations ceased on the EBT. It was as if at the end of the day everyone left, as they normally would. However, they would not return the next day. The EBT was left at a standstill — well preserved. Kovalchick Salvage Co. purchased the property for scrap, but never dismantled the railroad. Instead in Aug. 13, 1960, Nick Kovalchick began operating the railroad as a tourist attraction, giving rides along the line. This proved to be so popular that operations continued for the next 40 years. Today, the Friends of the East Broad Top are working to restore the railroad to operation and tell the story of this little Appalachian coal hauler [see “East Broad Top fully reopens tourist-era line … ,” News Wire, Oct. 11, 2021]. Here are five mind-blowing East Broad Top facts.

No. 1: Water in a boxcar? Water goes in tank cars! Not on the East Broad Top

Hopper cars made up the majority of freight cars found on the coal-hauling EBT. A number of other car types, like boxcars, could be found on the roster, but in lesser quantities. Being a smaller railroad, the resourceful use of equipment was important to keep expenses down and solve the transportation challenges that occurred.

Challenges like keeping the mines at Robertsdale, on the southwest portion of the railroad, supplied with water. The mine equipment was steam powered with water normally drawn from two nearby reservoirs. Occasionally, in the late summer months, the heat would dry up the water supply. If the railroad didn’t find a way to deliver needed water the mines would shut down.

The EBT had only one tank car and it hauled oil. Why not move the water in boxcars? That is exactly what happened. EBT shop crews took several wood boxcars and caulked all the joints, sealing the car. The cars were filled partially with water that was hauled to the Robertsdale area and dumped in the reservoirs. Problem solved!

No. 2: At the first EBT board of directors meeting, what did they talk about?

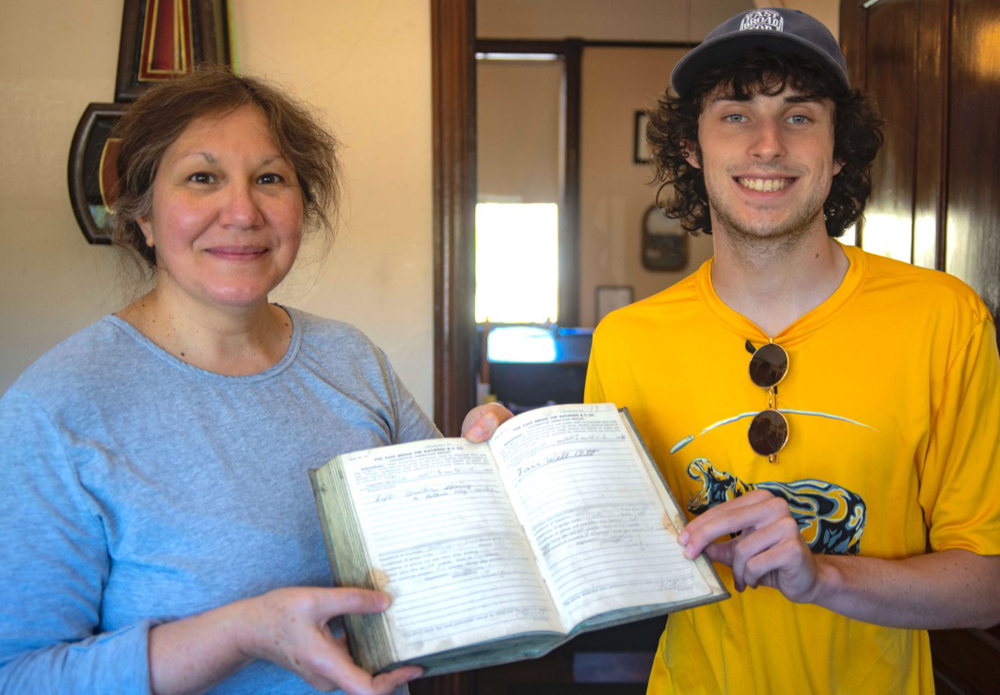

The EBT directors met for the first time in 1871, 151 years ago. The hand-written notes from the meeting still exist in the EBT archives. The issue here is not so much what they actually discussed, but that fact that the meeting notes exist and are accessible 151 years later. For that matter, thousands of pages of EBT documents were saved and today, are being preserved and cataloged.

The EBT has garnered accolades as one of the best preserved historic railroads in the U.S. A portion of this distinction comes from the fact that company records have been saved virtually since day one. You name it: from correspondence to meeting minutes, from engineering diagrams to car movement books, the documentation that tells the EBT story exists.

Today, those documents are being cataloged and stored in the Orbisonia Station in Rockhill Furnace, Pa. [see “East Broad Top hires archivist,” News Wire, June 21, 2021]. The station has three fireproof vaults ranging from 12 to 14 feet tall and being able to hold from 950 to 1,400 cubic feet of material. Right now, it is estimated that the EBT documentation could run up to 5,000 linear feet. That’s nearly a mile.

What did the directors talk about at that first meeting? You’ll have to do some research and find out. Fortunately, the records still exist.

No. 3: 3-foot gauge versus 4 feet 8 ½ inches. Don’t change railcars, just change the wheels.

Among the major disadvantages of narrow-gauge railroads is handling freight from standard gauge lines. The cars and track just don’t play well together between the two gauges. The EBT faced this challenge just like other narrow-gauge lines. The EBT, however, employed a solution that, although unusual, was resourceful and got the job done efficiently.

At Mount Union, Pa., the EBT’s interchange with the Pennsylvania Railroad, stood a bridge crane used to transfer lumber. By the late 1920s, the business had dried up and the crane was idle. In 1933, C.D. Jones, EBT general manager, devised a procedure, using the bridge crane, to solve the track gauge issue. The idea Jones developed was not new, other railroads had tried it, but not as aggressively as the EBT would. The procedure involved lifting first one end, then

the other of a freight car with the crane. With an end in the air, the shop crew would roll the standard gauge truck from under the car and roll in a narrow-gauge unit specially designed to fit the full-size car. Swapping trucks took time, but not the time and back-breaking labor of transloading an entire carload.

No. 4: When doing it by hand is better than with mechanical assistance

In addition to the shops, the EBT’s Rockhill facilities feature an eight-stall roundhouse and turntable. The turntable was originally an “armstrong” unit requiring four men to turn a locomotive. As heavier locomotives arrived, the turntable was fitted with an engine run off compressed air. The air pressure was supplied by the locomotive riding the turntable. This method produced an unwieldly ride. Ultimately, EBT officials decided that “man” power was better than compressed air. While the air engine remained, the turntable returned to manual operation. However, with the arrival of heavier locomotives, the four men required to turn a locomotive, climbed to six or eight.

No. 5: Belted in the shop

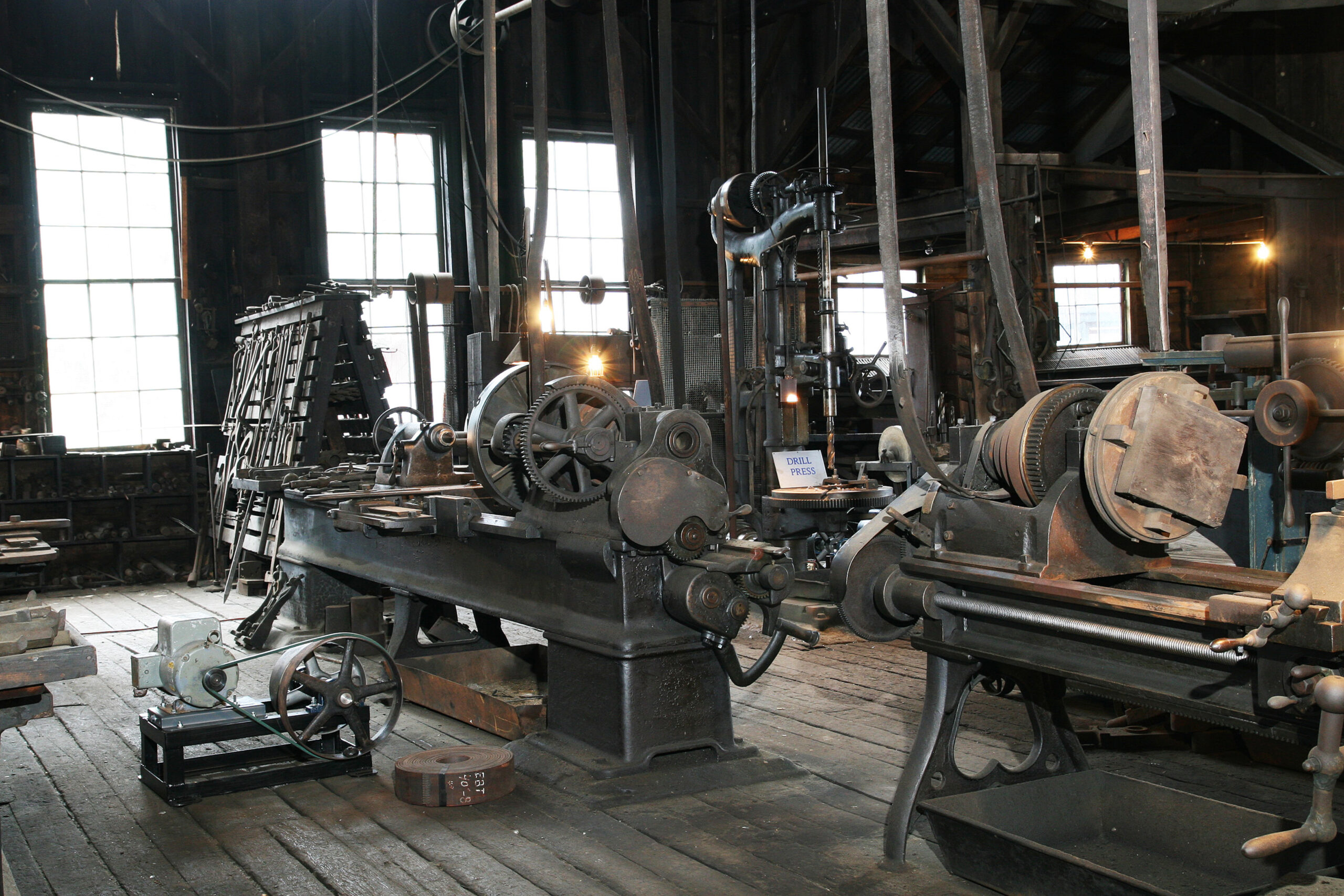

In today’s industrial shop, the operational noise of the machines dominates the environment. Listen closely. Mixed into this jumble of sounds, you’ll notice the whir of electric motors that drive the machinery.

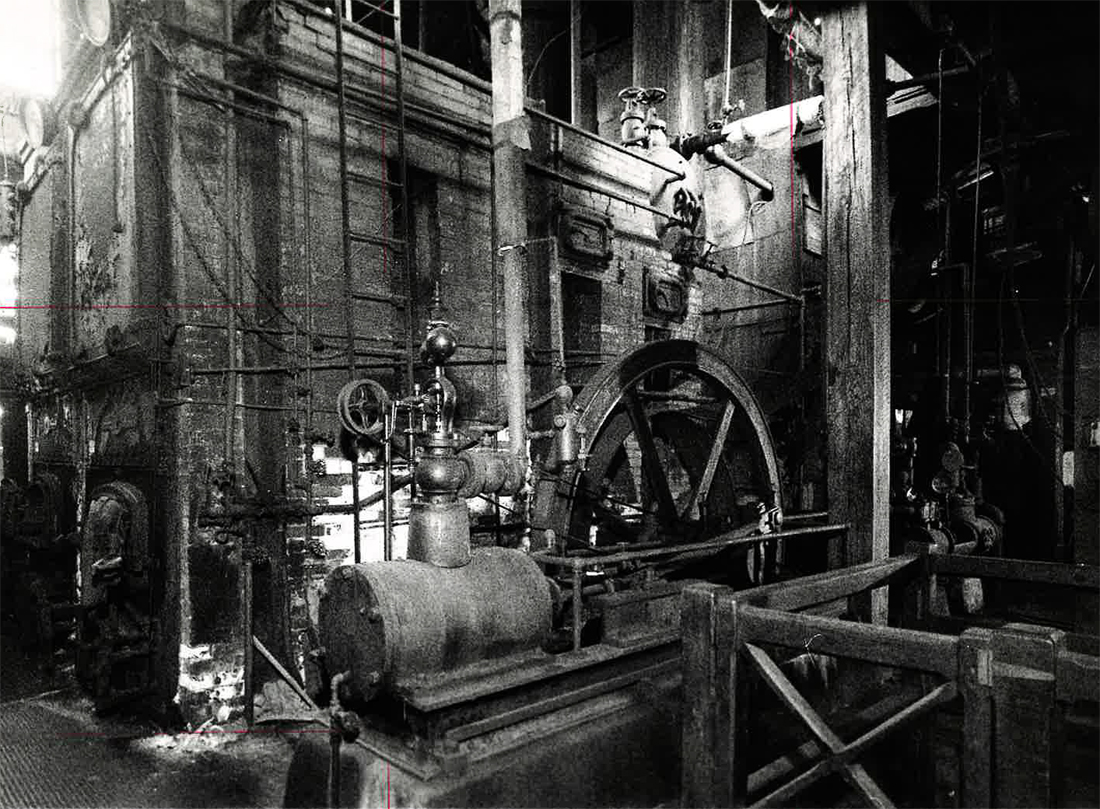

Roll the calendar back to the first operating period of the EBT and you will not find electric motors powering shop machines. Yet, the EBT shop took care of the railroad’s mechanical needs and did extra work for area residents and businesses. The shop was capable of rolling boiler courses, fabricating hopper cars, and turning wheels. Woodwork for passenger cars was well within their capabilities. This was a full-service shop. Powering it all was a 100 hp steam engine and an elaborate system of leather belts, wood pulleys, and overhead drive shafts.

A Babcock and Wilcox water tube boiler provided steam to power the engine along with a steam hammer, air compressor, water pump, sump pump, and electrical generator (for lights). The steam engine was attached, by belt, to the series of pulleys and drive shafts. From here, power was transferred to specific machines with additional belts.

By today’s standards, this was not the most efficient nor the safest shop environment. For the time, however, the EBT operated a fully functional shop.

Looking for more mind-blowing facts? Check out “Five mind-blowing Big Boy facts.”