Mind-blowing facts about the GM Aerotrain

By the 1950s it was clear that the passenger train was not the wave of the future. Automobiles and airliners were the next chapter in personal transportation for the United States. In some cases, however, the railroads wanted one more round in the fight to retain and regain passengers. General Motors took up the challenge posed by several railroads to construct a rail passenger vehicle that would be economic both to build and operate. The new vehicle was to be stylish, as well, in an attempt to lure people from the highways and skyways back to the rails.

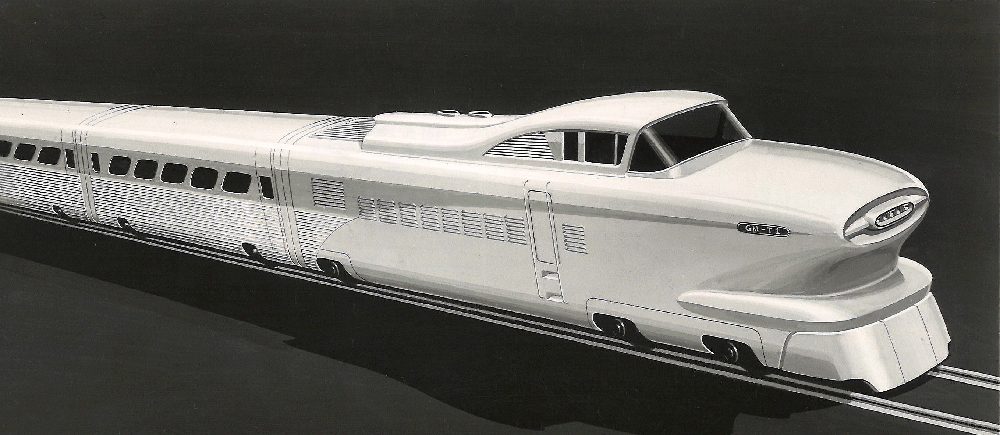

In 1955 the Aerotrain was unveiled. Lightweight and capable of 100 mph, the Aerotrain was designed to woo passengers with contemporary styling based on current automobiles. The 40-foot-long coaches, each riding on only two axles and weighing 16 tons, were GM bus bodies widened by 18 inches to rail width. The air-cushion suspension was similar to that being used by GM buses on the highway. And no wonder the Aerotrain could trace its design concepts to the automotive world, GM’s auto stylists, led by a 20-something Charles Jordan, were the creatives behind the project.

The Aerotrain concept was good. The ride provided by the train was not. Passengers complained that inside the bus-body coaches a trip on the Aerotrain was loud and rough. Railroads found the LWT12 locomotive lacking enough power. Many of the styling features made maintenance difficult. What was a solid idea on the drawing board was less so in the field, leaving the GM Aerotrain as an interesting transportation footnote. Consider these five mind-blowing facts regarding the GM Aerotrain:

No. 1: Coupling for power and air

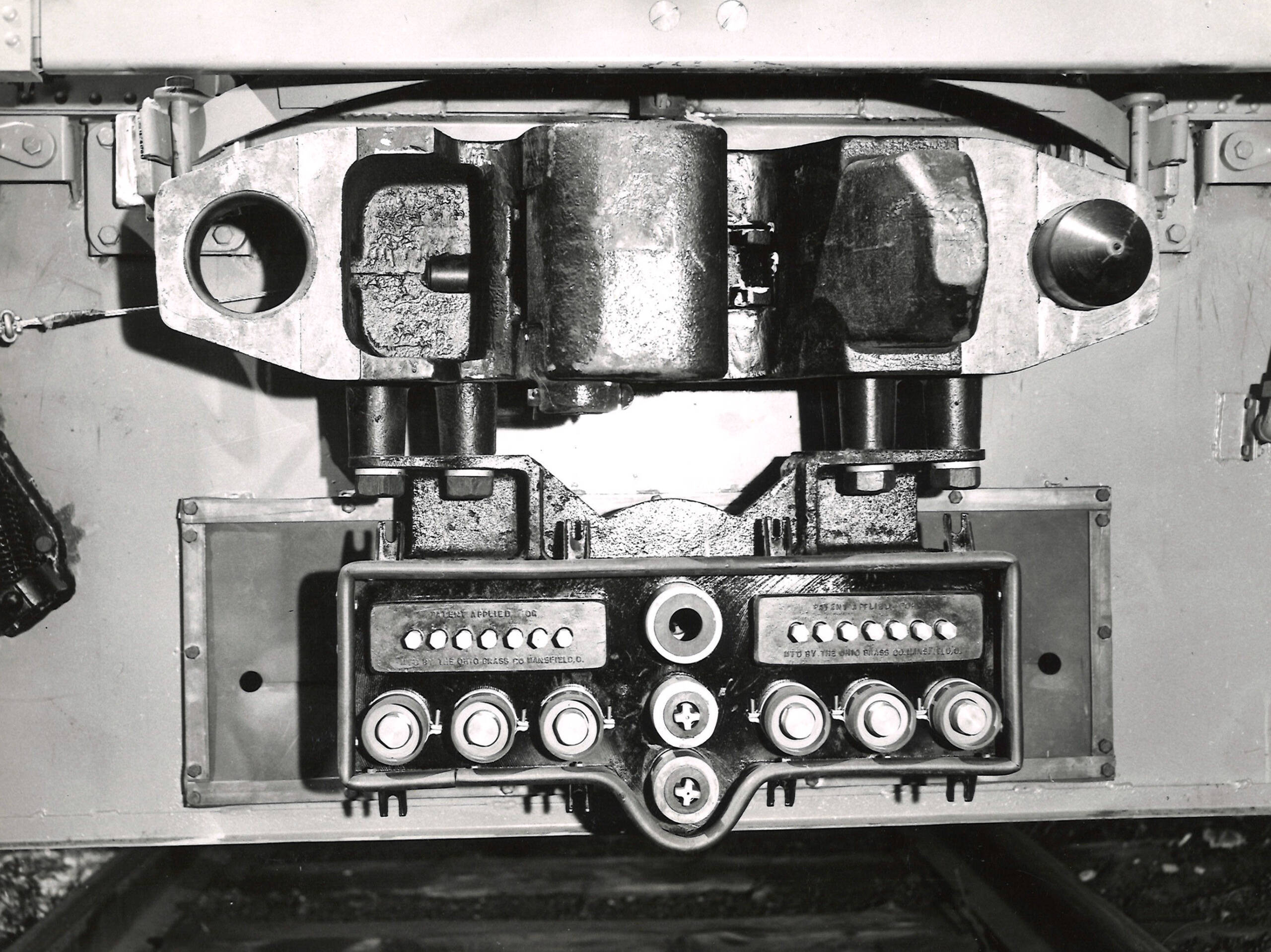

To maintain a streamlined look along the train and improve aerodynamics, the Aerotrain cars were fitted with full-width diaphragms. The cars also rode on a lower center of gravity compared with conventional passenger cars — 45 inches Aerotrain vs. 55 inches conventional. Making regular air hose connections between the cars was nearly impossible considering these arrangements. GM designed an innovative coupler system that not only secured the cars together, but automatically made air and electrical connections. The coupler, itself, was a smaller version of a standard automatic unit. To each side of the coupler were male/female pin arrangement to ensure proper alignment.

Below the coupler a bank of fittings came together in the coupling process to supply train-line air and electricity. The air line was standard to operate air brakes. The electrical connection was, however, an innovation. Beyond the 12-567C prime mover, the locomotive carried two 6-71 Detroit diesel generator sets, which provided electricity to power lights, heat, and air conditioning in the coaches.

No. 2: Who made that air conditioner?

When the name Frigidaire is mentioned, we generally think of home appliances — refrigerators, dishwashers, ranges, and air conditioners. From 1919 through 1979, Frigidaire was part of the GM empire. GM bought the company, originally called Guardian Refrigerator in 1919, for $100,000. By 1927, the name had changed, and sales soared to $15 million annually.

In addition to home air conditioning units, Frigidaire supplied small, powerful cooling machines for GM cars. If it could be done for cars, why not the Aerotrain? The Aerotrain’s coaches featured electric air conditioning, heating, and florescent lighting. While some form of these environmental amenities had become standard on passenger trains by the 1950s, being all-electrically powered was new to most passengers and railroads.

No. 3: Don’t refurbish, buy new

Remember the Aerotrain was designed for economy, both in fabrication and operation. This is one of the reasons, GM designers chose to use existing technologies from different company divisions. The technology existed, saving the cost of development from the rail up. In doing so, they also built in another GM principle: planned obsolescence.

Dating to the 1920s, planned obsolescence was developed by Alfred P. Sloan, GM CEO, and his associates. Many people believed that buying a car was a once-in-a-lifetime event. Such a consumer attitude dramatically slowed GM’s sales. GM’s goal was to get people to buy another new car — even if the one they had was not worn out — just to stay fashionable by driving the latest design. This is why automakers change models every year — another Sloan idea.

Railroads generally refurbished passenger coach approximately every 7 years. For the Aerotrain, GM did not want the railroad to refurbish, but to buy new. The plan was to remove the bus-body compartment from the chassis and wheels and scrap the whole thing. GM would then sell the railroad a new body — with the latest styling updates. The cost comparison: initially, the Aerotrain cars cost $40,000 each or $1,000 per seat (40 per coach). A standard passenger car, in the 1950s, ran around $2,200 a seat.

No. 4: Introducing the (little) Aerotrain

General Motors felt it had a solid rail transportation solution in the Aerotrain concept. Now the public and railroads had to be sold on that concept. GM utilized some of the normal mid-1950s advertising channels to pitch its new train. Splashy full-page ads printed in both color and black and white appeared in numerous national magazines. Thumb through Trains from 1956 and you will see Aerotrain advertisements.

GM’s line up of heavy-duty, innovative, and special purpose vehicles was not limited to railroad equipment. Buses, earth movers, tractors, trucks, and even aircraft were being developed by GM or had its parts on board. In its first 22 years (1933-1955), GM had produced engines totaling 100 million hp. To celebrate the occasion (and promote its products) GM staged Powerama from Aug. 31 to Sept. 25, 1955, just south of Solider Field along Lake Michigan in Chicago. Among the most popular of the 253 exhibits: a new full-size Aerotrain.

While Powerama was mainly outdoors, featuring larger-than-automobile sized vehicles, GM had been presenting another promotional show since 1949 — Motorama. Featuring mainly automobiles and other smaller products, the first Motorama filled a space at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. A wild success, GM began offering Motorama in several U.S. cities each year. For 1956, Boston, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, and San Francisco hosted the show. More than 2.2 million people visited Motorama that year and one of the GM innovations they saw was the Aerotrain — not the full-size version, however.

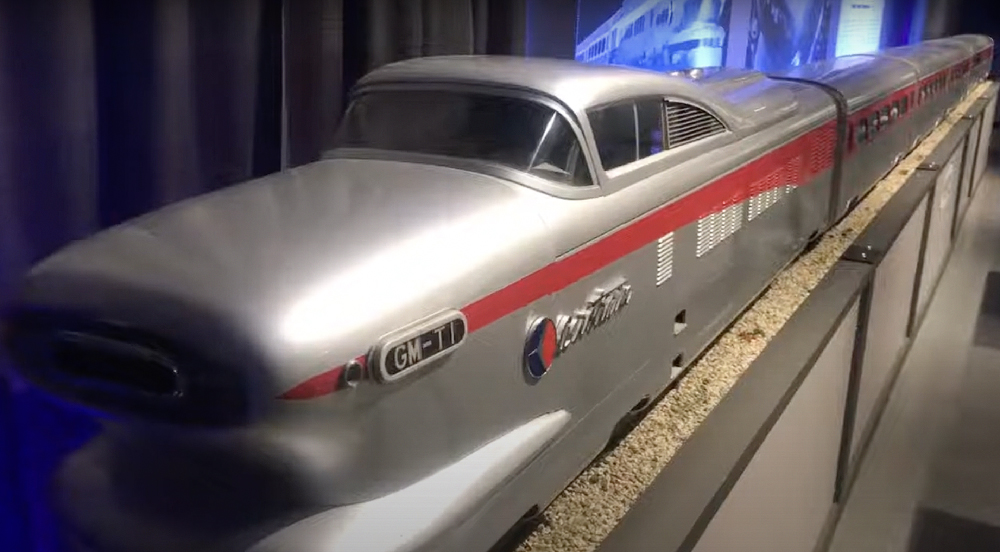

For Motorama, GM fashioned a 1/8-scale model of the Aerotrain. Fabricated from steel, aluminum, leather, and plaster, the model showcased the LWT 1200 locomotive and all 10 cars of the train. Stretching nearly 100-feet long, the model was perched on hand-laid track in the midst of a futuristic-looking display. The coach interiors, decorated with wallpaper identical to what was in the prototype, featured plaster-cast seats with plaster passengers. Interestingly, each car was machined and assembled individually, meaning no two cars were exactly the same — although one couldn’t tell from looking at the display.

Today it is widely known that two prototype Aerotrains — LWT 1200 locomotive and two coaches each — are part of the collection at the National Museum of Transportation (St. Louis) and the National Railroad Museum (Green Bay, Wis.). The 1/8-scale model is part of the National Railroad Museum collection, as well. Currently, the model locomotive and five of the 10 cars are displayed. [see “Diesel locomotive delight,” Trains.com, May 25, 2010]

No. 5: Liberace and the Crap-shooters’ Special

The New York Central, Pennsylvania, Santa Fe, and Union Pacific all agreed to test drive the Aerotrain. The New York Central ran the train between Chicago and Detroit and then Chicago and Cleveland. On the Pennsy, tests started with a New York-Pittsburgh route and were shortened to Philadelphia-Pittsburgh. Santa Fe tried the Aerotrain as a San Diegan, between Los Angeles and San Diego.

The Union Pacific tried the Aerotrain in what could be the most extreme manner. UP added the train to its “City of” streamliner fleet, naming it and lettering it the City of Las Vegas. To the dismay of the railroad, passengers soon labeled the train the Crap-shooters’ Special. A 9 a.m. Los Angeles departure reached Las Vegas at 4 p.m. The train then left Las Vegas at 5:30 p.m. reaching Los Angeles at 12:15 a.m. With this schedule meal service was needed. The UP converted one Aerotrain car into a lounge and a second into a buffet. The $16.35 round-trip ticket included a full meal with seconds from the buffet.

The Hollywood-style hype promoting the train was capped with a celebrity appearance during the first run. As the City of Las Vegas pulled into its namesake town, Liberace, the flamboyant piano player, and showman, appeared waving from the cab. It was the perfect capper to the fanfare UP had assembled to greet the train.

The Viewliner Train of Tomorrow ride, two trains which ran in Disneyland from 1957 to 1958 was modelled on the Aerotrain.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viewliner_Train_of_Tomorrow

What a combo, junky bus on rails and planned obsolescence. GM at its best?

A friend bounced to Pittsburgh on the Aerotrain. PRR was jointed rail then; he said he almost got seasick.