Mind-blowing facts — New York Central passenger trains

We are 50-plus years into the Amtrak era, which began on May 1, 1971. A few Amtrak trains still carry the identity of the conveyances they imitate — California Zephyr, Empire Builder, and Crescent — to mention a few. What lives on today is a contemporary train — traveling a route similar to the original, but not quite — that is a shadow of their forebears. When it comes to American passenger trains, names like the Super Chief, City of New Orleans, or Capitol Limited evoke a hushed reverence and the legend of exceptional service, comfortable accommodations, fine food, and a schedule well maintained.

If these few name trains are the stuff of legend, then the New York Central, its Great Steel Fleet, and trains like the 20th Century Limited are the stuff legends are made of. Many have argued that the 20th Century Limited was the finest passenger train on American rails. Argue how you like and long for the days of yore, but either way come along now for a glimpse behind the legendary standard passenger trains of the New York Central. There is more to the story than meets the eye across all the years. These are five-mind blowing facts about the passenger trains of the New York Central.

No. 1 — The Century by the numbers

The New York Central’s top passenger train was the 20th Century Limited. It was an all-Pullman, extra-fare, luxury liner running between New York and Chicago on a 15-hour schedule in 1948. An early-1930 advertisement by the NYC stated that: “The 20th Century Limited long since ceased to be a ‘train.’ It is a daily fleet of trains.” In the 12 months prior to the ad’s appearance, the NYC had dispatched 2,153 trains carrying the 20th Century Limited name. That works out to almost six sections of the train daily. The record day came in January 1929 when seven Century sections traveled eastbound from Chicago to New York carrying 822 passenger.

Each Century section required a crew of nearly 70, which is a ratio of one crew member for every 1.75 passengers. Included among the staff were sleeping car porters, dining car waiters, stewards, cooks, maids, barbers, manicurists, valets, and secretaries.

Equipment-wise, the NYC kept 24 locomotives and 122 identical luxury sleeping cars on standby to meet demand and or mitigate negative situations impacting the Century’s schedule. The schedule, by the way, was guaranteed to the point that the NYC refunded each passenger $1 for each hour the train was late. Also, the 122 standby sleepers, as with all cars assigned to the Century, had to be turned so that passenger room windows faced the waters of the Hudson River going into or coming out of New York. The NYC paid attention to the smallest detail so passengers would have the best travel experience.

No. 2 — The Wolverine and My Old School

Grab those stereophonic headphones, it’s time for a trip back to 1973 …

I remember the 35 sweet goodbyes

When you put me on The Wolverine up to Annandale

It was still September

When your daddy was quite surprised

To find you with the working girls in the county jail

I was smoking with the boys upstairs when I

Heard about the whole affair, I said oh no

William and Mary won’t do …

Dial the volume down from 10 and let’s interpret what you just heard. This is the first verse of the song My Old School from the group Steely Dan’s 1973 album Countdown to Ecstasy. Band leaders Donald Fagen and Walter Becker tell the story of getting caught up in a pot bust at their old school — Bard College — in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. The incident happened in May 1969, a time when “long hairs,” like Fagen and Becker, were targeted for their behavior — real or imagined.

The Wolverine was a New York Central train running from New York to Chicago, and was popular transportation for Bard students. The train ran an interesting route, ducking into Canada after Buffalo, N.Y., and returning to the U.S. at Detroit, before a final sprint to the Windy City. It carried both sleeper and coach accommodations.

The time visited in My Old School was a time when The Wolverine, like many passenger trains, was in decline. Starting in 1957, the train lost its observation car. By December 1967, The Wolverine was no longer a named train, merely appearing as Nos. 17/8. During the Penn Central period, the train remained numbered only — westbound, Nos. 61/17. Eastbound, No. 14, was truncated at Buffalo, with passengers needing to change trains at 2:30 a.m. in order to reach New York.

Interestingly in all of this, The Wolverine never stopped in Annandale-on-Hudson. The closest NYC station to Bard College was 8 miles away in Rhinecliff, N.Y. Finally, today’s Amtrak Wolverine, running between Chicago and Pontiac, Mich., via Detroit, is a direct descendant of the original NYC train … although neither of them would actually get you to my old school.

No. 3 — Would you like butter with that?

The 20th Century Limited epitomized the concept of a passenger train being akin to the finest hotel or steamship, but one that glides along steel rails rather than remaining perched on a foundation or cresting the next wave. During the Century’s heyday, its two arch-competitors could be found in the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broadway Limited, and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s Capitol Limited, both of which also ran a New York-Chicago route. It has been reported, that all else being equal in the mind of the passenger, the choice of which train to take sometimes came down to the dining car the passenger preferred.

If a passenger liked butter, the 20th Century Limited was the way to go. Beginning with the Century’s inauguration in 1902, Dr. William Seward Webb, a Vanderbilt relation and president of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad over whose tracks the Century ran west of Buffalo, N.Y., became the official source for the train’s butter provision. Webb owned a hobby agricultural venture — Shelburne Farm, located on the shores of Lake Champlain in Vermont. For a hobby farm, the operation was stunning, featuring well-maintained, prized herd of purebred Hereford cattle. From here, Webb produced the luscious creamy butter served aboard the Century.

For each passenger, the Century carried one pound of butter. The butter was served at table in the dining car and also used in the kitchen for cooking. However, whether traveling New York to Chicago or Chicago to New York, a pound of butter was allotted for each passenger. “ … the diners of the Century may will have rolled on butter in their journal boxes,” commented noted author and photographer Lucius Beebe in his book on the train.

No. 4 – Beer and NYC trains don’t mix

New York’s Grand Central Terminal stands as an icon in the railroad world. Since opening on Feb. 2, 1913, millions have passed through its spectacular halls, beginning, or ending a long-distance journey or merely as part of a daily commute. The Terminal’s construction solved a significant neighborhood problem, by putting the trains underground and converting Park Avenue, running north of the station, into a boulevard befitting the posh uptown neighborhood the area was becoming.

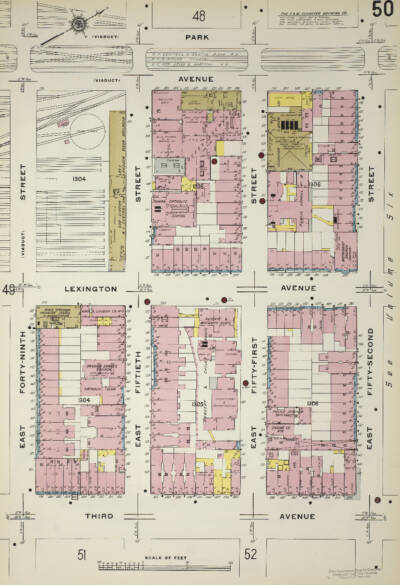

Constructing Grand Central’s two levels of track required massive excavations along Park Avenue. From 42nd to 50th street 1.6 million yards of rock were drilled and removed along with 1.2 million cubic yards of earth. More than 200 buildings were razed as the terminal site expanded from 23 to 48 acres.

One of the many construction challenges that arose appeared in the two-block area bounded by Lexington and Park avenues and 50th and 52nd streets. Roughly a third of these two blocks were occupied by two schools and church, another third by businesses and apartments. The last third, and the largest single landholder was the F.&M. Schaefer Brewing Co. The brewery fronted Park Avenue and for many years enjoyed having a street-level siding. With the tracks being moved below street level, the brewery’s siding was gone. More disturbing, however, was that the drilling vibrations and the close proximity of the railroad excavations to the brewery threatened underground lagering cellars.

Despite the setbacks and danger, The F.&M. Schaefer Brewing Co. did not protest the planned expansion. On Nov. 22, 1902, according to the New York Times, former city controller Ashbel P. Fitch, representing the brewery, stated, “ [F.&M. Schaefer Brewing Co. will] not stand in the way of any great public improvement, and that although they had already suffered by the closing of streets, they were willing to suffer more for the public good.”

Ultimately, Schaefer Brewing closed the Manhattan plant, sold the incredibly valuable land, and built a new brewery in Brooklyn.

No. 5 — Late to its own funeral

Into the 1950s, the 20th Century Limited, like other passenger trains was in decline. The allure of faster jetliners and the freedom of the automobile had taken its toll. The last run of the Century was announced for Dec. 2, 1967. The announcement really wasn’t a big announcement, but rather a whisper in an attempt to reduce the fanfare around the great train’s demise.

Only half full, the Century departed from Grand Central Terminal track 34 at 6 p.m. The fanfare was minimal: a group of railfans gathered on the famous red carpet, taking photos of observation-lounge Wingate Brook, which brought up the rear of the train. Beyond that was the press, taking photos of the railfans. Aboard the train, despite the crew putting on a good face, the equipment was worn, and it was clearly the final trip.

In the dark of night, west of Harbor Creek, Pa., another train had derailed, blocking the Century’s path. The train sat still for hours until it was detoured over the Norfolk & Western. In the end, the last run of the 20th Century Limited limped into Chicago around 6:45 p.m. — 9 hours, 50 minutes overdue — late to its own funeral.

It is true that, beginning in the late 1950’s, a number of our

country’s crack trains began to have some of their amenities

whittled away. But whittled is, I believe, the correct word.

In fact, it was the middle or late 1960’s before one could

detect any significant downgrade to trains like the

North Coast Limited, the Empire Builder, the Super Chief/

El Capitan, the Denver Zephyr – or even the

Broadway Limited (which remained all-Pullman – and

STAFFED by Pullman – through 1967). This is what makes

the wholescale downgrade of the New York Central’s major

intercity trains in the late 1950’s so disheartening. Between

1958 and 1961, everything which could be done to slow down, diminish and “un-polish” what up to that time had

been a first class operation was done: Observation cars removed, the Ohio State Limited’s running time increased

by two and a half hours, St. Louis through service eliminated entirely, transcontinental cars dropped … and on

and on and on. The Century, of course, took major hits,

beginning with the elimination of the “Century Club” with

its bar, telephone, barber, shower-bath, secretarial services,

public address system and distinctive “tony” look and feel.

This being said and acknowledged, one thing which has always struck me is they never got rid of Grand Central’s 260 foot red carpet. This would appear to be an “easy” cut –

and yet … no matter how chipped the paint was on those two-tone gray sleepers, no matter how unreliable the

air conditioning, that red carpet remained until – apparently – the next-to-last day. People say the food on 25/26 actually

got better as the sixties wore on – maybe. I’ve heard over

and over about superb crew members like York Battey, who

presided over the observation/lounge/sleepers – undoubtedly true. But in general, the New York Central,

very early in the post-war years, became extremely negative

about passenger service – ALL passenger service. Yet

somehow, they couldn’t – or wouldn’t – undo one of the

iconic symbols of the Great Steel Fleet at its finest: the

Century’s red carpet.

Item 5, concerning the demise of ‘The Century’ reminded me of a meeting on or about December 2, 1967 to which I and several other Operating Department Management Trainees had been “invited” by our boss, Vice President of Operations Robert Timpany. Our Uncle Bob, as we called him behind his back, was known to all as a hard-nosed, no-nonsense railroader. This made it all the more notable when he opened the meeting with, “Gentlemen. The Twentieth Century is dead. We will NOT have a moment of silence for it.” and then took a long, slow drink from the water glass in front of him before getting to the reason for the meeting — giving us our assignments in support of the Empire Service starting that week.

The “Beebe” book on “The Century” is a real prize winner. His writing style is very entertaining. In another vein, his, (and Charles Clegg’s) private car, the Virginia City, is up for sale. It was once owned by Wade Pellizzer, a friend and fellow member of the old Peninsula Model Railroad Association in San Mateo, CA. I was told it’s listed at Ozark Mountain Railcar.

Sorry Bob, but if the (122) sleepers had been turned as you state, then the room windows would NOT have faced the Hudson in one direction. To maintain the constant orientation of sleeper windows to the river, the sleepers were not turned but the more complex switching operation of reversing the position of the head-end and observation cars had to be undertaken.

DO remember, on the New York Central Remains COULD be checked to VALHALLA. There was a public notice in the Harlem Division timetables.

Anyone know when that last happened?

When I was younger I thought “remains” were baggage & shipments to be picked up later. I noted in 1964 the limited number of Boston & Maine stations that stilled handled “remains”.