Orphan Trains

The orphan train story does not involve a specific train consist, locomotive, route, or even schedule. The story comes from a period that was socially different from today — 1854 to 1930. Attitudes about the idea of family, how parents cared for children, and the dichotomy between well-off and not, were radically different than what is currently accepted and even changed within the era we are discussing.

During this time, passenger trains rose to the way we traveled. When child-welfare advocates, like Charles Loring Brace and his New York Children’s Aid Society, developed plans to aid the destitute and orphaned children of growing eastern cities, the railroads became a conduit to the solution.

Let’s discuss the orphan trains in five mind-blowing facts:

No. 1 — Don’t give us your poor, your orphaned …

In the 76 years during which orphan trains operated, a child would find themselves on board for a variety of reasons, some shocking to us today. In larger eastern cities, especially New York and Boston, there arose a youth population who were legitimate orphans — those having lost one or both parents to illness, accident, or another calamity. If there was no one to care for these true orphans, they often took up street life — hawking newspapers, collecting rags for recycling, or engaging in thievery and other petty crimes.

Another facet of this wayward youth group were those abandoned by parental choice. As factory mechanization rose, employment opportunities and wages decreased. In many cases, parents could either not find gainful employment or earn enough to provide for everyone at home. Children, again, were forced into questionable activities to support themselves or the larger family. In extreme cases, of which there were many, parents would outright abandon children in order to support themselves or trim the family to a manageable size.

During the same period, the gulf between wealthy and poor increased, with the upper class not wishing to have poor children littering the streets or otherwise interfering with their upper-class lifestyle. Street children often found themselves arrested and jailed as criminals simply for loitering. While introduction to the criminal justice system got them off the street, it did not solve the long-term plight of the orphaned and abandoned children — someone still had to care for them.

No. 2 — A “Brace”-ing solution

Charles Loring Brace grew up in Hartford, Conn. An 1846 Yale graduate, he went on to study at the Yale Divinity School and Union Theological Seminary. After schooling, Brace found he preferred missionary work as opposed to being stationed in a particular church. In 1853 he founded the New York Children’s Aid Society to address the needs of New York’s newsboy population. The Society soon grew to encompass care for all wayward children by finding them new homes, providing shelter, food, clothing, and education.

In this time, Brace helped develop a theory, that promoted, in his words, “Entire change of circumstances as the best cure for the defects of children of the lowest poor.” Translated: take the children from their current environment, cut all ties with the past situation and those involved, and place them in a new, wholesome domain. Thus, the concept of “placing out” came to be. It was felt that the poor children should be taken from the cities and placed in small town farm homes or similar surroundings in the Western United States — those states today considered the Middle West.

No. 3 — The “company” train

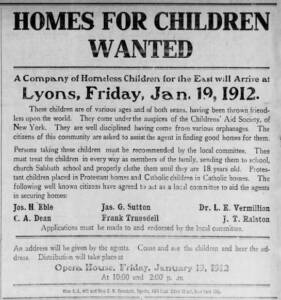

Depending on which organization was conducting the placing out journey the details of what happened would vary. Generally, however, the process followed this pattern: Most of the children’s welfare organizations had field agents responsible for locating communities, and even specific homes, for children. Agents gained such information through placing ads in local newspapers promoting the availability of children to loving homes, for farm work, or to undertake domestic chores. On occasion first-hand discussions with local church or civic leaders would unearth the need or desire for the placement of children within a community. Once a town or towns was identified, the aid organization would select children meeting the local criteria — more boys ages 10 to 16 for farming needs, girls from 5 to 12 for domestic service, true orphans from age 2 to 16 for those wishing to add an additional family member.

Children were assembled into “companies” ranging in size from five to 30. With an adult leader, the company boarded the train on a lower-class coach ticket and set off for their new community. The company’s journey would take days, sometimes more than a week, as only the lowliest trains were used. A nurse or other adults would occasionally travel along depending on the ages in the company — someone had to be responsible for the diapers of the youngest “little wanders,” as they were called.

Upon reaching the designated community or preselected towns en route, the children were paraded from the train and taken to a local meeting hall, church, or even lined up on the depot platform. Adults desiring a child would visit the lineup to pick up the one they ordered or inspect the lot and make a selection. In many cases, while siblings may have traveled together, they would be separated during the selection process. Some knew where family members were taken, others did not rediscover brothers and sisters for years, if ever.

By today’s standards, there was an appalling lack of documentation recording the entire process. Remember, Brace and other placing-out advocates believed that all ties with the past needed to be severed for the new, wholesome environment to have the greatest impact on a child. There were no legal adoption papers prepared. The new parents were asked to promise, verbally at best, that they would care for the child, provide a good, loving home with food, clothing, education, and a moral upbringing. There were cases where children were indentured to their new parents until age 16. In such cases the parents pledged instruction in a trade — farming, mechanical work, or domestic arts — while the child was expected to work regular hours, not take any wages during the indenture, or attempt to leave the new home.

The local agents were expected to make follow-up visits at varying intervals but being stretched thin and with thousands of children placed annually, the visits generally did not come with regularity, if at all.

No. 4 — Mustard sandwiches

The orphan train ride could be exciting, terrifying, and monotonous for the little wanderers. For many it was the first train trip of any distance or their first journey by rail, period. This excitement was easily checked by the unknown of what was to come. Siblings generally rode together, only to sometimes be separated along the way or at their destination town. As much as older children would fiercely cling to younger relations, in hopes of keeping a family together, the adults had their way, separating brothers and sisters.

Before leaving the big city, children were polished for the journey. They were bathed, sometimes given haircuts, and were dressed in fresh clothes. The clothes, mostly hand sewn, came as donations by aid society supporters.

Mostly the orphan train trips were monotonous for the children. Riding for days at a time, they were lulled into boredom with little activity on the train and always being under the stern, watchful eye of an escort. Adding to the monotony was their food. Children were fed in their seats from supplies brought along by company leaders. Generally, every meal consisted of mustard sandwiches or jelly on plain bread. Orphans interviewed in adulthood about the train experience have been quoted as swearing off mustard and jelly for life.

No. 5 — Did it work?

In the 76 years of placing out in the United States it is estimated over 200,000 children were moved from Eastern big cities to the West. Some sources say this number is low, while others argue it is exaggerated. By numbers alone, society of the time must have found some redeeming value in placing out. There is no doubt the majority of the little wanderers grew to be productive, happy adults, some did not. With the lack of records throughout the program, we can paint a picture of the results, but cannot compile an unbiased, scientific study conclusively illustrating the impact of orphan trains.

In the end, social attitudes changed, leading to further development of legal adoption, a more palatable option. Additionally, states favored for placing out — Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska — began legislating to slow or ban child importation. The feeling was that the Eastern big cities, especially New York and Boston, were dumping their problems on the rural states, when they should be taking care of them at home. Interestingly, big Midwestern cities — Chicago, Indianapolis, and Detroit — began developing some of the same youth challenges as New York and Boston. These Midwestern cities adopted the placing out solution while complaining about being the dumping ground for Eastern problems.

Did placing out work? It depends on your point of view. For social advocates, like Brace, yes, it provided new opportunities for children. For the wealthy of New York and Boston, yes, it was an effort to clean out the city. For the farmer, yes, generally, it brought needed help to the expanding agricultural industry. For the children, yes and no. Some did find new, loving homes, and learn a trade. Others were simply torn from a parent or parents who did not want them or could not afford them — a tough sentiment to deal with.

For the railroads: it was passenger business, and they became a means to the end.

There is much more to the Orphan Trains story. Please visit the National Orphan Train Complex Museum and Research Center for more reading on this aspect of American railroad and social history.

I suppose there were few trains in the lands where most America’s indigenous Indians were sent. Doubt that the “Trail of Tears” would have been much happier had trains been used.