Learning the route

Because trains have a maximum speed, most people assume they move at that speed constantly. Not so.

You can’t simply set the cruise control at 79 mph and forget it. With the exception of very flat, sparsely populated terrain, you’re constantly applying or releasing the brakes and manipulating the throttle. There are conditions dictating that you must slow down. Additionally, there’s always someone ahead, unable to make speed. That can really put a dent in your on-time performance.

So how does a train’s engineer know when to slow down or speed up? Like the old joke, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” followed up by the punch line, “Practice, practice, practice.”

First, a student engineer has to undergo months of classroom and hands-on training. Once technically certified, the fun really begins — physical characteristics qualifications. Before Amtrak was empowered to hire its own operating crews, freight railroads furnished engineers and conductors by contract. The limits over which they could run a train was very locally oriented. I could run freight and passenger trains. My seniority was good from Richmond, Va., to Portsmouth, Va., Raleigh, N.C., or Florence, S.C. I knew the authorized speeds like the back of my hand, and felt comfortable at the controls of the Silver Meteor, the Orange Blossom Special piggyback run, coal trains, locals, or yard jobs.

I ran passenger trains exclusively when I became an Amtrak employee in 1986, but my territory radiated from Washington, D.C., to Atlanta, Ga., Savannah, Ga., Newport News, Va., and Hamlet, N.C., as well as Pittsburgh, Pa. It took months to learn each route. To maintain my qualifications, I had to be tested and re-tested on the operating rules, signal systems, and territory of eight different railroads. I was thankful for daylight runs, because I could see the road ahead. Learning the Capitol Limited, largely in the dark between Washington and Pittsburgh — 334 speed changes in 331 miles — took me six months. It is necessary to learn your speeds and braking points in the both directions.

The risk for making a mistake, even a tiny one, carries with it the loss of your job — or your life.

It was a wonderful feeling to have the host freight railroad’s local road foreman of engines certify me to run trains over his rails. When I was being tested on the Southern Railway, between Raleigh and Charlotte, N.C., on the Carolinian, I kept it “right on the money,” each way. They’ve always had a notorious, no-tolerance speeding policy.

“I’m going to tell Amtrak you’re okay to go,” the road foreman told me at the conclusion of our trip. “But if I catch you doing that again, I’ll bar you off our railroad.”

“What did I do wrong?” I asked.

“You kept it right dead on speed. I prefer a mile an hour or two UNDER.”

“You don’t have to worry about me, sir. I’ll run it with the wheels in the air and the roof on the rails, if you wish.”

As such, I earned a reputation for compliance — well, at least on the Southern.

Check out the previous column, “From the Cab: How fast ya’ going?” from retired Amtrak Engineer Doug Riddell.

If you want to know what can happen when the engineer is not trained on a new stretch of track before operating a revenue run, look no further than the 2017 Amtrak derailment in Washington state. (See Wikipedia: “2017 Washington train derailment.”) The engineer missed cues that he was approaching a 30 mph curve at the end of a long straightaway, and the train was doing 78 mph when it left the rails. Three people were killed, 77 injured, and the train wound up on Interstate 5. The NTSB found that the engineer had “only one operating trip in the dark travelling in the opposite direction” prior to the derailment. ‘Nuff said.

Hi Bruce,

Who wrote “My Fifty years on the SP”?

David

Two questions: Surely you didn’t run the entire length of these long segments in one shift, did you? Example Washington-PGH 300 miles, about 8 hours today. And, are the railroads good about maintaining the speed limit boards up-to-date, like the one in the photo at Richmond?

Speed signs get knocked down for maintenance work…if you don’t manually remove them machinery will mangle them. But sometimes they don’t get immediately put back up. You just know where you are…and do what you are supposed to do. The signs are helpful…but you don’t actually NEED them.

Doug, on another subject: a reprint of your book is long overdue.

Maybe you are using these articles to develop another book?

Did you ever read, “My Fifty Years on the SP?”

Great book.

The railroad is a great place to create stories, if you don’t get killed doing it.

Yes, on some routes.

When I ran from Washington to Pittsburgh, I had a fireman/assistant engineer, with whom to share those long runs. Amtrak has the option of having two engineers in the cab of a locomotive if their end-to-end schedule exceeds 6 hours. Today, an engineer can contractually run alone from Washington, DC to Raleigh, NC, or Richmond, VA to Florence, SC, because the carded time is less than 6 hours. (And here, let me explain that there may be other routes where those same conditions apply. I use the Mid Atlantic, because that’s the area with which I’m most familiar.)

Bruce,

When I retired from Amtrak in December 2012, my first project was going to be writing a second “From The Cab.” I must admit that I got sidetracked though.

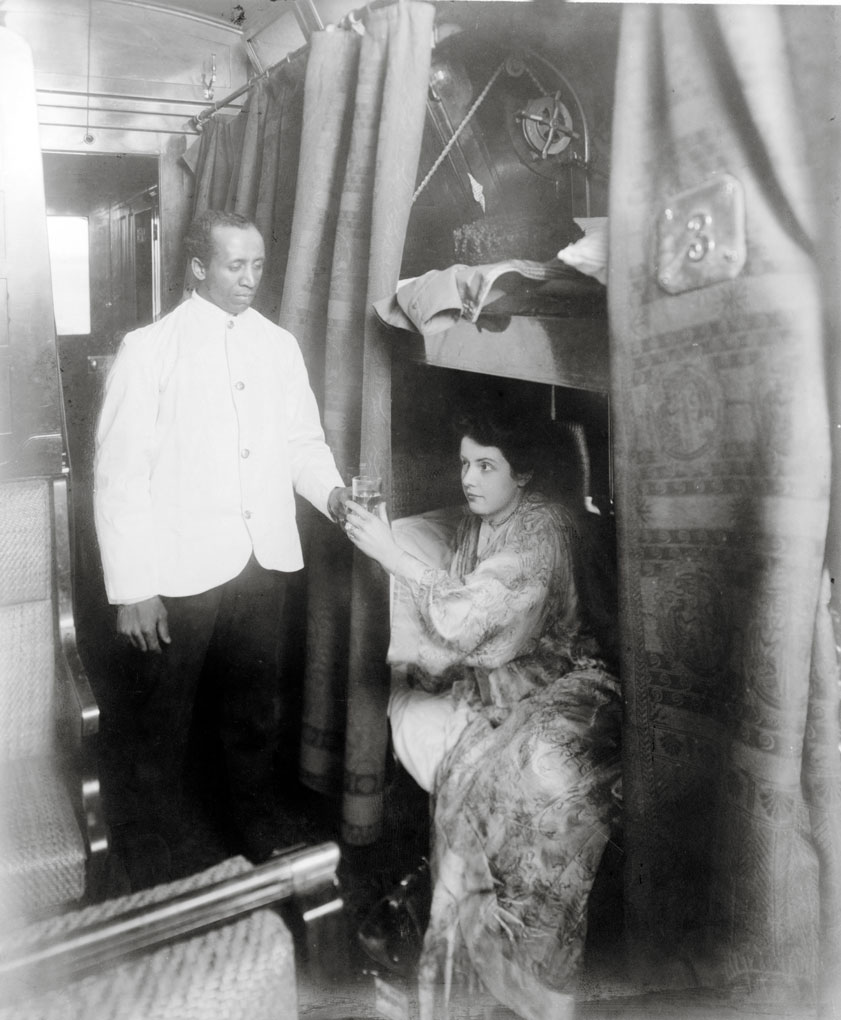

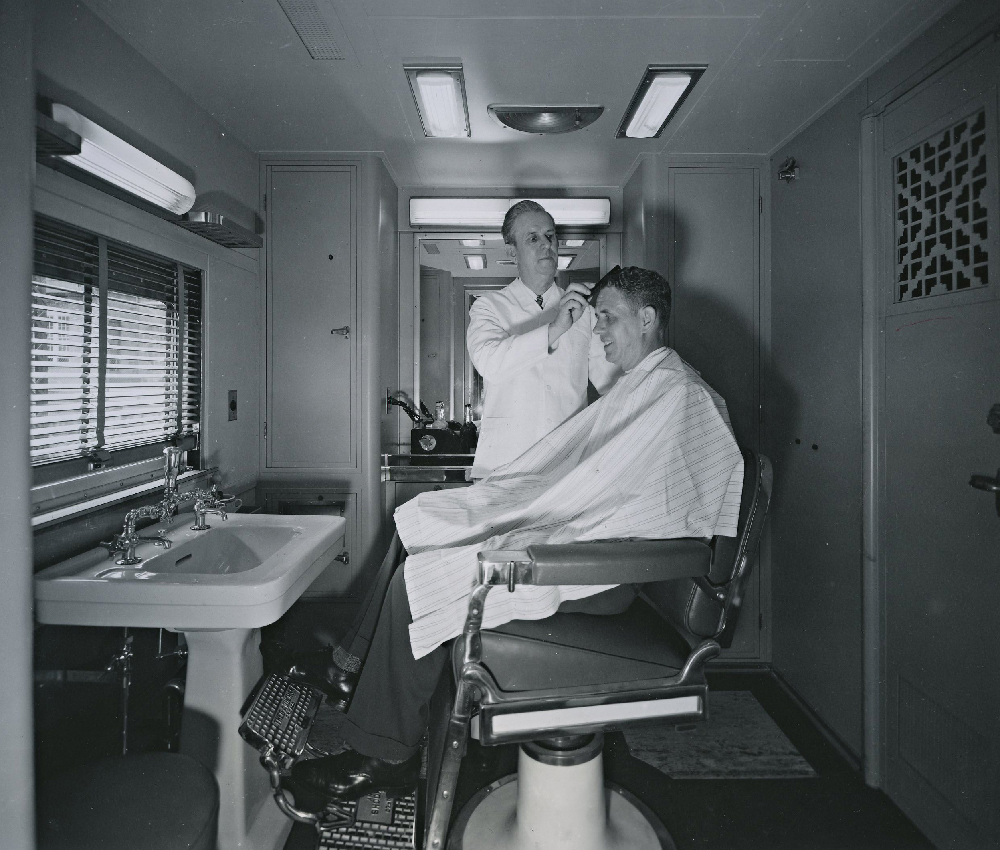

At my retirement party, I was approached about doing (and ended up accepting an invitation to write) a regional interest book, Virginia’s Legendary Santa Trains–a look at the special holiday season operations of special trains that gave youngsters the opportunity to meet ol’ St. Nick–who invited them to shop at the department stores that sponsored them. Afterwards, the RF&P Railroad Historical Society underwrote the publication of separate books about the original Gene Garfield auto-train, and another about Amtrak’s Auto Train. I’d love to do a sequel to From The Cab, since it was written in 1999. In the ensuing years I garnered more anecdotal material about railroad life, but more importantly, my role as Amtrak company photographer, working for president, Joe Boardman, expanded my sources of material. Again, I’d love to if my readers would enjoy them.

Doug…we would enjoy it if you could write it!

When I first qualified, I must be getting senile since I forgot the official name of a test run, my trainer said I would be railroading by the seat of my pants at first.

He was right. Running over the undulating hills, I found myself at the beginning constantly going too fast or too slow.

I never thought I could learn every tie in my route, but I did.

We ran track that was either 10 or 25 mph.

In the middle of night, I would very briefly nod off, and then ask myself, “Did I blow that last crossing?”

I envied my Grandfather who would run UP passenger trains at 90 mph.

He did it the same way Bill Taylor of NS did, running N&W’s classic 611 J all over the Mid Atlantic. Where he wasn’t qualified, he was accompanied by a pilot engineer (who was territorially qualified), usually with the local road foreman of engines in the cab. I got to move the 611 in the yard one time, but never got out on the road with it. My best friend was called from the extra board for a trip over SCL, and I begged him to let me take the call–even telling him that I’d let him have the pay. He declined though, and I waved at him as I took pictures from trackside.

Maybe this has been answered somewhere else, but I haven’t seen it: How does Ed Dickens run 4014 all over the UP system? Is he qualified everywhere? Is he running with a pilot? A local Road Foreman? Are there times when a local man is at the throttle?

He has an engineer pilot…someone who regularly works the route and tells him where he is, and what he needs to do.

Another great story Doug, a question though, when you ran Amtrak to Savannah was that on ACL or SAL lines? Our farm is 10 miles from Fairfax and I travel monthly to Beaufort passing through Yemassee so I get to see traffic on both old RR’s. Thanks again for great RR memories.

John Zwemer,

I had “rights” to run from Florence, SC to Savannah, GA (over the former ACL), but never exercised them. I had the same rights to run from Charlotte to Atlanta. I preferred working close to home, but to have done so would have meant relocating, so I was fortunate enough to work near enough to home (Richmond, VA) that I never had to relocate.

Thanks for the reply Doug, and I vote YES!! to another edition of From The Cab.

I have at various times been qualified Hinton to Newport News, both river and mountain. And Martin KY to Shelby, and Martin to Hazard. That was at one time about 600 signals! They’ve thinned them out as you know.