Read Part 1!

Transcontinental Railroad track laying leads to this moment

Finally, by April 1869, after Promontory Summit, Utah, had been agreed upon as the meeting point, Central Pacific’s Crocker determined to build 10 miles of track in a single day. By then, the Union Pacific was too close to give Casement another chance to do better.

Work began the morning of April 28 with the unloading of the first of the ready supply trains. That took scarcely 10 minutes, and the sound of the falling rails was like thunder. Rails (30-foot rails were now being used), spikes, and splice hardware for 240 feet were loaded onto each of 12 tracklaying cars, and the first was pushed to the end of track.

Unloading rail on the Transcontinental Railroad

Loaded, these cars weighed more than 5 tons. Horses were used to pull them except on downgrades. Immediately after the car stopped, its crew slid the outermost of the rails sideways onto the car’s rollers. Two men with rail tongs grabbed one of these rails and pulled it forward off the car, while two others did the same on the opposite side. As the rails were rolled off, two other men grabbed the moving “heel” of each rail and, upon the command “down,” both rails were set onto the ties. Another man waiting at the far end placed a gauge on their ends. These eight men of the “iron” or “rail crew” were Irish, though most of the workers were Chinese. The various foremen were mostly Yankees.

The men closest to the car were known as “heelers.” They inserted shims between the rails at the joint and lined the new rails with the rails under the car. When all was good, one heeler pulled a gauge left in front of the tracklaying car, the foreman called “good iron,” and the six-man car crew pushed the car ahead 30 feet to the new end of track. The gauge that had been pulled from in front of the tracklaying car was taken ahead 60 feet by yet another man in anticipation of the next rails. Thus, the gauges were moved in leap-frog fashion.

With 240 feet of rail laid, the track car was empty. It was immediately pushed back onto spiked rails, tipped onto its side to clear the track, and the next loaded car rolled forward. The car crew rode their car, and they had to stop and tip it aside every time they met a load going forward. It required 22 loads to deliver the materials for a mile of track. Before the first 2 miles were completed, the next supply train moved to the front and was unloaded by other teams.

Joining rails on the Transcontinental Railroad

As the track was extended, the splicers jumped into action. First “peddlers” dropped joint hardware at each of the joints. “Head strappers,” waiting on each side of the track, quickly installed the joint bars and finger-tightened one nut and bolt. They then moved to the next joints. Behind them, “back strappers” installed the remaining nuts and bolts. Following behind, others pulled the shims and tightened the nuts and bolts with long-handled track wrenches. Joints were spliced before spiking to assure that adjoining rails were in perfect alignment.

Spiking rails on the Transcontinental Railroad

Spikers followed close behind the splicers. Like the splicers, they were specialized. The “head spiker” started his spike 16 inches from the end of the joint tie on the line side of the track (as denoted by the cord used by the tie setters to line the ties). He started his spike and then walked ahead to the same spike on the joint tie of the next rail.

Behind him, a “nipper” levered the tie over until the half-driven spike was snug against the rail while the “inside spiker” set his spike, locking the tie and rail together. Then they walked ahead. With the rail set on one side of the track, a “gauger” with a track gauge and a “gauge liner” with a pinch bar adjusted the position of the “gauge rail” (moving the rail). When it was right, the “gauge spikers” started the spikes locking that rail to the tie. Once they had started their spikes, they moved ahead to the same tie in the next panel.

Other spikers started the spikes on the intervening ties, first the middle tie in the panel, and then the others in a systematic sequence. Behind them came “high spikers” who finished driving all the spikes home. They were accompanied by more nippers who levered low ties up against the rail base so the spike-tie connections were tight. To avoid the confusion of men passing one another, each spiker struck a particular spike in each panel only once, and then all moved ahead to the next panel in unison. Thus each spike was driven by a succession of men advancing at a measured walk, swinging their mauls. They paused only to allow loaded and empty railcars to pass. Most of their time and energy was spent walking forward. Following the spikers was a company of men armed with picks, shovels, and tamping bars moving dirt under each tie, leveling and lining the track.

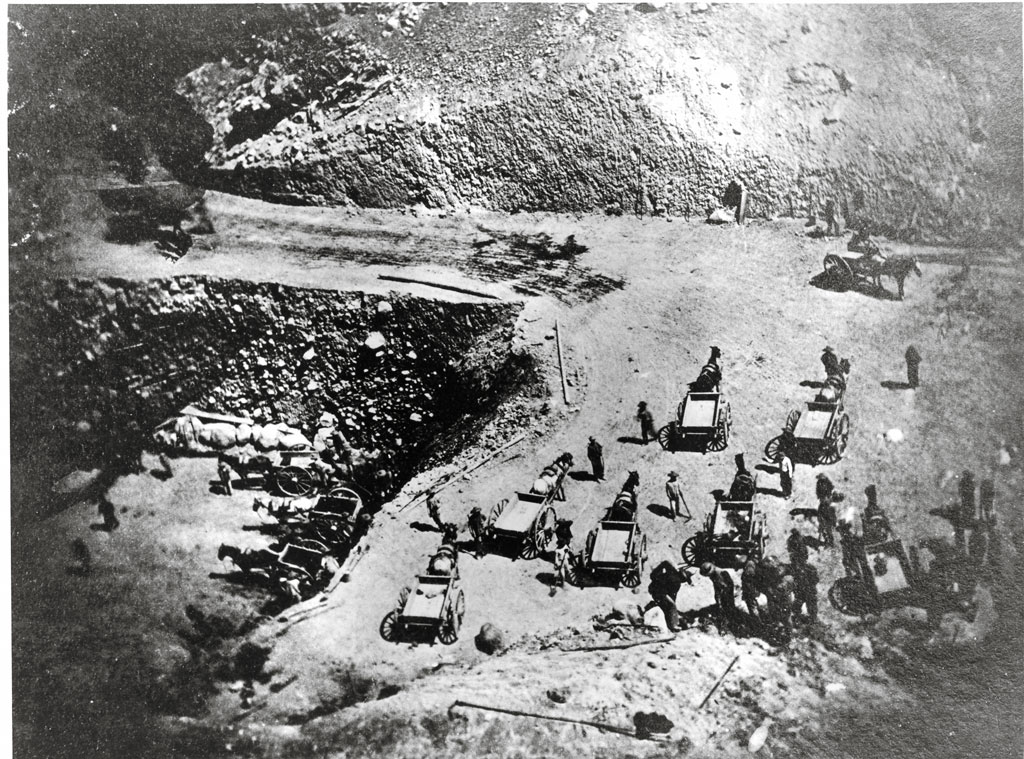

Central Pacific’s track laying assembly line

The entire string of workers, from rail crew to the last man with a tamping bar was stretched out for 2 miles. They moved like a machine, performing their well-choreographed dance. Beside this moving assembly line, a seemingly endless parade of teams with wagons hauled ties to the tie setters working well ahead of the rail layers. Ties had already been distributed two miles before the day began. But all the ties set that day that were hauled from a supply yard 2 miles behind the morning’s end of track.

Transcontinental Railroad track laying at 80-feet per minute

For 6 hours and 42 minutes, before breaking for lunch, a fresh tracklaying car appeared at the front every 3 minutes. The rail crew unloaded a pair of rails every 10 seconds, emptying the car in 80 seconds. With the car empty, they had nearly 2 minutes to catch their breath while the empty car was exchanged for the next load. They set the pace for the entire army of men who moved forward at roughly 80 feet to the minute. Waterboys were everywhere. At mealtime the kitchen cars were pushed to the front and 1,100-1,400 men were fed. Almost 6 miles had been built.

The afternoon was anticlimactic. Bending rails and an ascending grade slowed the pace. At 7 p.m., the iron crew came to the last tie — said to be the last available tie for 50 miles. They had covered a few feet more than 10 miles. It was almost dark when the last of the pick and shovel men joined them.

Reason for laying 10 miles of Transcontinental Railroad track in one day

Huntington had needed every mile of track weeks earlier to bolster his argument to the Secretary of the Interior that the CP should connect with the UP at Ogden. From his perspective, the 10 miles built on April 28 came too late. He wrote, “[It] was really a great feat, and more particularly so when we consider that it was done after the necessity for its being done had passed.” Huntington missed the point that the men had not exerted themselves that day for the company. They did it for themselves. Witnesses commented on the rivalry between the companies and the workers’ enthusiasm. They related that the eight-man rail crew refused relief, wanting instead to lay every rail themselves. They were making their mark. It was pure sport.

We do not know the men of that long-gone army of workers. A few faces stare out from old photographs, and we have a handful of their names. We do not know them, but we certainly know of them. They are the men who set a record by building 10 miles of railroad track in a day — when it was not necessary. We, who never even walk 10 miles in a day, let alone build a railroad while doing it, still tell of them 150 years later.

Finding identities for the workers

No CP document has been found that identifies the former UP track layer who taught the CP Casement’s method of track building. However, subsequent newspaper reports reveal that he was almost certainly David J. Sullivan, a young Irishman, working his way across the country, perhaps to join a relative already working on the CP. He stayed with the company until the road was completed. Subsequently, he directed track construction on the Virginia & Truckee, the Nevada Central, the Carson & Colorado, the Nevada-California-Oregon, and the Verdi Lumber Co., spelled with intervening employment as a section foreman or roadmaster on some of these same railroads. He died in Reno, Nev., in January 1918. Unfortunately, no photograph of Sullivan has ever been identified, though he likely appears in photographs taken at Promontory.

Because he showed the CP how to lay track in a hurry, allowing the company to meet the UP in the Salt Lake Valley, Sullivan may well be the most important unsung hero of the first transcontinental railroad.

Want to find out more about the Transcontinental Railroad?

Facts, figures, history, and more are available from our special Journey to Promontory magazine, available at our partner shop, the Kalmbach Hobby Store.