Road foreman

As a young engineer, age 38, I was appointed road foreman of engines on the Lehigh Valley Railroad working out of Sayre, Pa. My territory ran from Coxton, Pa., to Manchester, N.Y., which is half way to Buffalo, N.Y. It was in 1953 and the job lasted until 1955 when I was fired — I mean my position was abolished!

As a life-long railroader — entirely on the Lehigh Valley — I basically had one job and worked for one company, except for the two years driving a taxi in Auburn, N.Y., at age 19. I started in 1936 as a hostler in the Auburn yard on the branch bearing that city’s name. In 1944, I was appointed engineer, spending most of my time on the branch.

Apparently, because of my young age, the management recognized me as having promotion potential, and so in February 1953, I became a road foreman of engines.

This entailed moving to the Sayre office — in the big passenger depot — and working on the main line. I wore a suit, white shirt, and tie, had an office and a secretary. It was a great job and I felt I was on my way. Most of my responsibilities were tied to riding the engines on various runs and instructing both engineers and firemen on the proper handling of diesel locomotives.

Early on, however, I faced much resentment from crews since they were mostly older and more experienced. Many resented “a kid” telling them what to do. Compounding this was the fact I had spent almost my whole career thus far on the Auburn Branch, not the main line. Even my secretary said everyone believed the job should have gone to a “mainline man,” adding he should have been considered for the promotion.

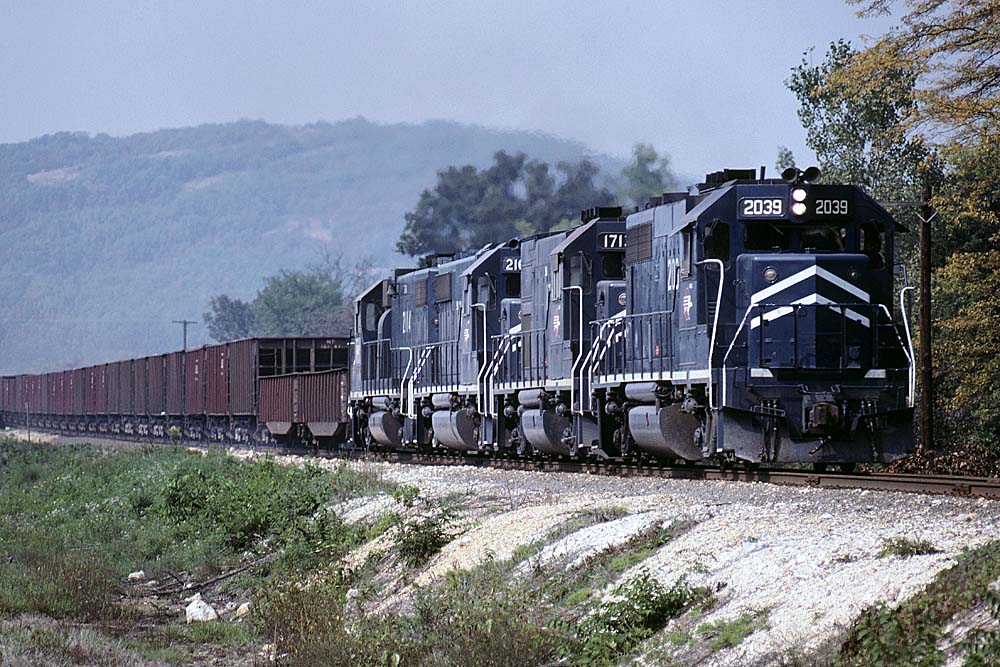

In 1953 handling a diesel-powered train was still relatively new. The Lehigh Valley sent me to the Electro-Motive Division plant in La Grange, Ill., for school where I learned F-unit basics. Many of the old timers were unfamiliar with handling long freights with up to four diesel units and the concomitant problems involved in starting, stopping, tractive effort, and braking. I had learned the basics and was expected to help them, despite some uncomfortable moments.

I remember one time while riding No. 9 to Buffalo from Sayre — the railroad’s premier passenger train, the Black Diamond — Jim Lantz, who retired in 1955, was the engineer with two Alco PAs, each packing 2,000 hp. These engines were used on all passenger trains, with EMD and Baldwin diesels assigned to freights. Even though I was in charge, Lantz thought he had enough years to be assertive, and was! I was riding in the brakeman’s seat, when suddenly he said, “Get your ass over here and run this thing instead of just sitting there.”

I ran the train, making all the stops until I got to Batavia, N.Y., about 55 miles east of Buffalo, when I turned to Lantz saying, “You take over from here.”

“You’re afraid of the terminal, aren’t you?” was his reply, referring to the upcoming Buffalo station.

“You’re damn right I am.”

The station in Buffalo had a train shed with stub-end tracks. One had to bring the train right up to the end and stop just short of a big concrete block guarding the end of the track. Being unfamiliar with the passenger units, I was not about to chance bumping the block, damaging the front coupler, or severely jarring the passengers.

The new position was fulfilling. It felt as if I was on my way up the management ladder when my downfall began in 1955.

Aside from the tourist aspects of Niagara Falls, N.Y., there are chemical plants, oil storage tanks, and other industries. To service these companies, the Erie, New York Central, and Lehigh Valley partnered with the Niagara Junction Railway. This local, electrified switching line was owned equally by the parent companies but was run independently with its own operating rules.

The Niagara Junction Railway was formed in 1898 as a subsidiary of the Niagara Falls Hydraulic Power & Manufacturing Co. The Erie, New York Central, and Lehigh Valley acquired it in 1948. The Niagara Junction Railway was dissolved as a company when Conrail took over in 1976.

In spring 1955 the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers on the Niagara Junction went on strike. The parent railroads, in an effort to keep the line running, as well as to teach the engineers a lesson, decided to use their own crews for switching.

Since all available engine crews on the Lehigh Valley were occupied, some of us management personnel were sent to the Niagara Junction. Not being privy to what was going on, I and a few other road foreman were instructed to take the morning train to Buffalo — No. 11, the Star. From my division, Vic Cole and I were dispatched.

The next day there was a meeting with the superintendent, C.W. Baker, who later became Lehigh Valley president for a few months in 1960. We were informed that the company wanted us to go up to the Falls in two days and run the engines. That night Vic and I headed back to Sayre, taking one of the Lackawanna’s trains. We wanted to get home earlier than the Lehigh Valley trains would allow. As we were eating in the dining car, Vic asked, “Jim, what are we going to do?” I told him I just couldn’t cross the picket line, I wouldn’t do it.

“I knew you wouldn’t, me neither,” he stated. We informed Mr. Baker of this fact.

Two days later each of us received a letter from Superintendent Baker indicating our jobs had been abolished. The Lehigh Valley didn’t usually fire people. They merely abolished their position. In my case, Mr. Baker wrote, “Jim, this is the second time we asked you to do something for us and you refused.” The first incident, according to the letter, was when an engineer from Buffalo had an affair with another woman, and I was to speak to him about it. This was the early 1950s and marriage was a contract for life. I had told Baker I couldn’t interfere with another man’s personal life. The railroad did not see my point of view.

After reading my letter, I walked right over to the crew dispatcher’s office and marked up for the next day’s Binghamton job! I still had my rights and seniority as an engineer. When I told my wife, she exclaimed, “Thank the Lord! Now no more calls at 2 in the morning to go to some derailment.” I went back to my previous job and loved every minute of it.

My pride was hurt, but I was resolved not to let my fellow union guys down. I remembered my grandfather, also a Lehigh Valley engineer, who crossed the picket line once and paid for it for the rest of his career from the other men.

Vic Cole was so hurt that he suffered a nervous breakdown and needed professional help. He didn’t have much seniority and could only hold a fireman’s job on a Sayre yard engine.

Sometime later, I had just finished an evening run and was walking to the station when another engineer by the name of McIntosh stopped me. He came over, wrapped his big Irish arms around me, giving me a bear hug. “Jim,” he said, “we knew you wouldn’t cross the picket line. We knew you wouldn’t let us down.” Being respected like that meant more to me than anything!

I shall never forget his big bear hug.

Years after C.W. Baker became railroad president and Vic Cole had recovered, Vic would tell people, “Yeah, I got fired, but it took the president of the railroad to do it.”

This story was told to Guy Kinney.