We all talk about railroad preservation. We all want to be sure our favorite locomotives, depots, sections of track, rights-of-way, or what have you continue to be available for people to enjoy and learn from well into the future. What better time to talk about railroad preservation than in May, declared National Preservation Month by the National Trust for Historic Preservation?

The Center for Railroad Photography & Art has focused attention on the topic in its online feature, “Railroad Preservation in a Nutshell.” Others may have other ways to recognize our heritage. But for all of those interested in any facet of railroads and railroad history, preservation is an integral part of railroad activity.

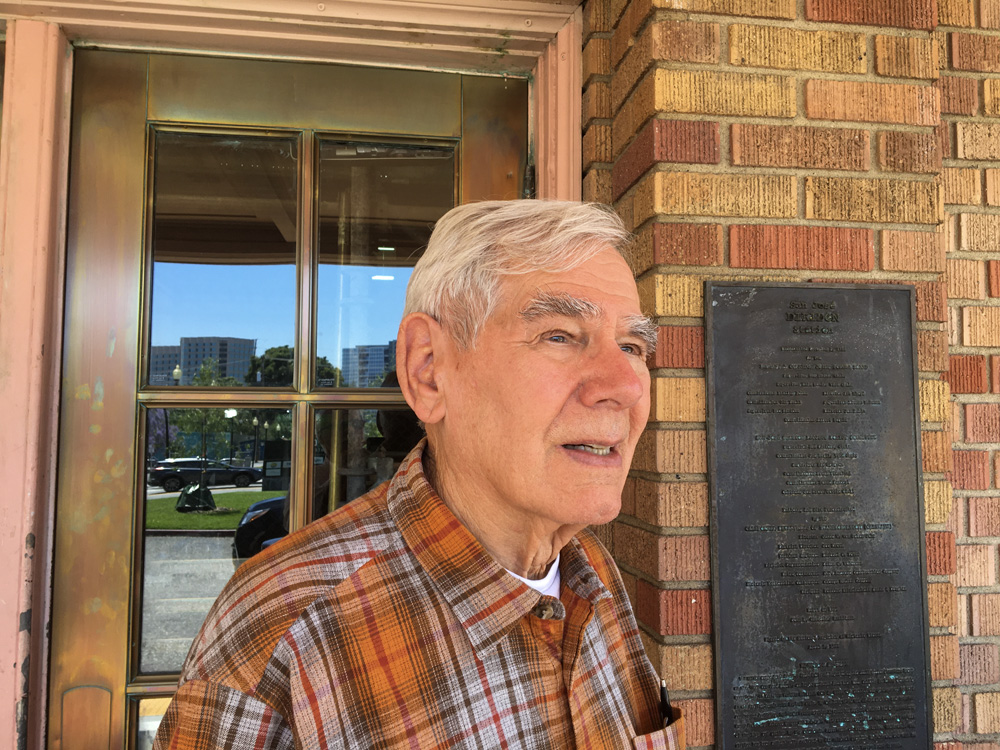

“Railroad Preservation in a Nutshell” honors John H. White Jr., a history professor at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, who in 1990 retired from the Smithsonian Institution as its curator of transportation. His thirteen books on early locomotives and passenger and freight cars – a signal achievement in the written history of America’s industries, not just railroads – are invaluable for preservationists. His many articles include, most recently, “Elisha Talbott and the Railway Age” in Chicago History (Winter 2010).

Fortunately, we railroad enthusiasts are not alone in our quest for preservation. It is also the policy of the U.S. government, proclaimed in the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which is a good model for us. It declares that “the historical and cultural foundations of the nation should be preserved as a living part of our community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people.” The law also suggests that because of growth in urban centers, highways, and residential, commercial, and industrial developments, and because governmental and private historic preservation programs are inadequate, the federal government needs to accelerate its role in preservation. Railroaders should heed the admonition to preserve.

The cover of Trains magazine’s special issue, Historic Trains Today, provides a good example. It depicts the colorful, wood-burning steam locomotive, the Eureka, already listed on the National Register of Historic Places, America’s official list of cultural resources worthy of preservation. The Eureka operates on the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad, itself a national historic landmark in Colorado.

Nearly every element of railroad infrastructure, individually or collectively, has been listed on the register: 1,500 stations or depots, 525 properties in historic districts, 60 locomotives, 12 roundhouses, four enginehouses, 12 hotels, and 395 engineering features such as bridges and tunnels. In addition, 19 railroad corridors are on the register.

The story of American railroading begins in 1795 with a small gravity line in Boston used on Beacon Hill to remove dirt from the excavation for the commonwealth’s capitol building or statehouse. Ever since, railroads have captivated the public’s imagination, enough so that preservation soon got underway. To explain railroad preservation, the Center selected for its Web site technical and historical landmarks that illustrate the connections among preservation, popular culture, and railroads. (We welcome your suggestions.)

Preservation needs begin with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the 25th railroad in North America, but the first common carrier. On July 4, 1828, a heavily symbolic date in U.S. and railroad history, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Md., the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, laid the first stone of the B&O in Baltimore. The stone was moved in 1992 to the B&O Railroad Museum, a mile east, and a historical marker was erected at the original site.

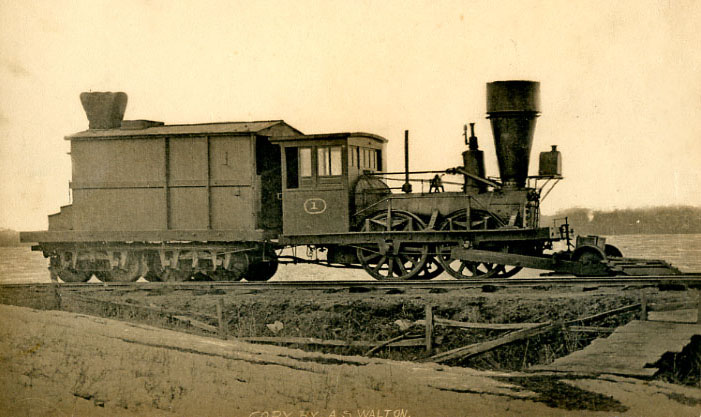

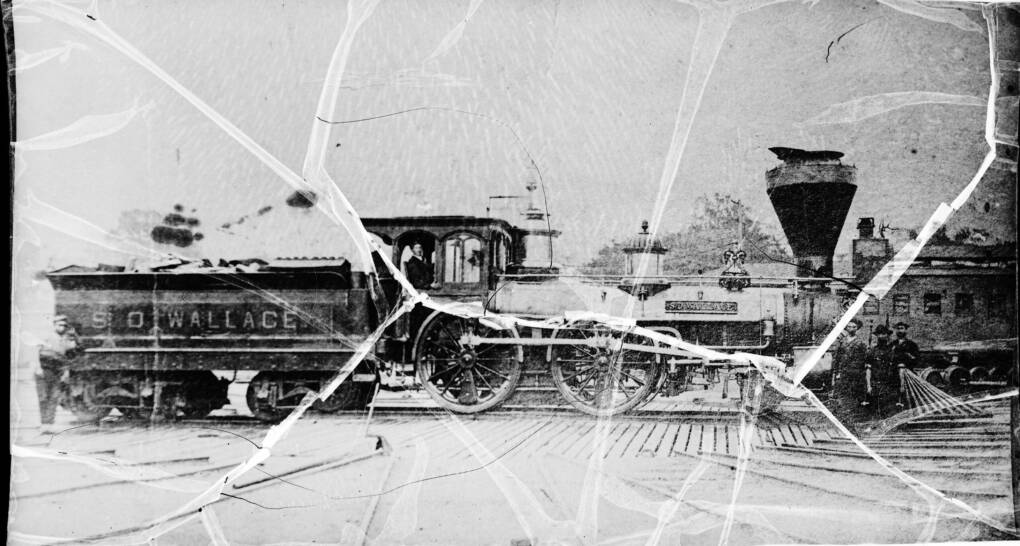

Other preservation highlights – many of which remain to be marked – include technical and historical landmarks that illustrate the connections among preservation, popular culture, and railroads. Especially significant is the Pennsylvania Railroad’s donation of the locomotive John Bull to the Smithsonian Institution in 1884, its first technology exhibit. And, there are many ties to popular culture through railroad songs, paintings, toy trains, children’s books, and movies. Sites related to some of these should be considered for the register and landmark status. Transitions in railroading, such as steam to diesel locomotives and the demise of small town depots, have spurred preservation, just as, in turn, the creation of the register spurs on us railroad-minded souls today in our continuing efforts. The national preservation program is, in fact, reciprocal. The people created it, and the program creates interest in other people.

The “Preservation Nutshell” listings conclude, currently, with the Leviathan, a replica of the Jupiter, the Central Pacific’s locomotive at the golden spike ceremony in 1869. The replica made its first public appearance at Train Festival 2009 at Owosso, Mich. The event featured eight operating steam locomotives. More than 36,000 people turned out for the four-day festival to see the locomotives and exhibits – a fitting 21st century tribute to hardworking railroad preservationists. May the nominations of the register continue, and may we railroad enthusiasts be imaginative and scout out suitable locations for many more – especially the subtle sites that will honor the railroad’s place in popular culture.

JOHN GRUBER is a long-time Trains contributor, founder and president of the Center for Railroad Photography and Art, and editor of Railroad Heritage. He has been a freelance railroad photographer since 1960, and received a railroad history award from the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society in 1994 for lifetime achievement in photography.