In addition to everything else the American Civil War might have been, it was also the first reliably documented major conflict. A combination of well-kept “Official Records” and preserved photographs give us a unique view into the first modern, industrialized, documented war. These images are only a sample of the rich documentary resources available from the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the tens of thousands of books, articles, and images created to document the Civil War.

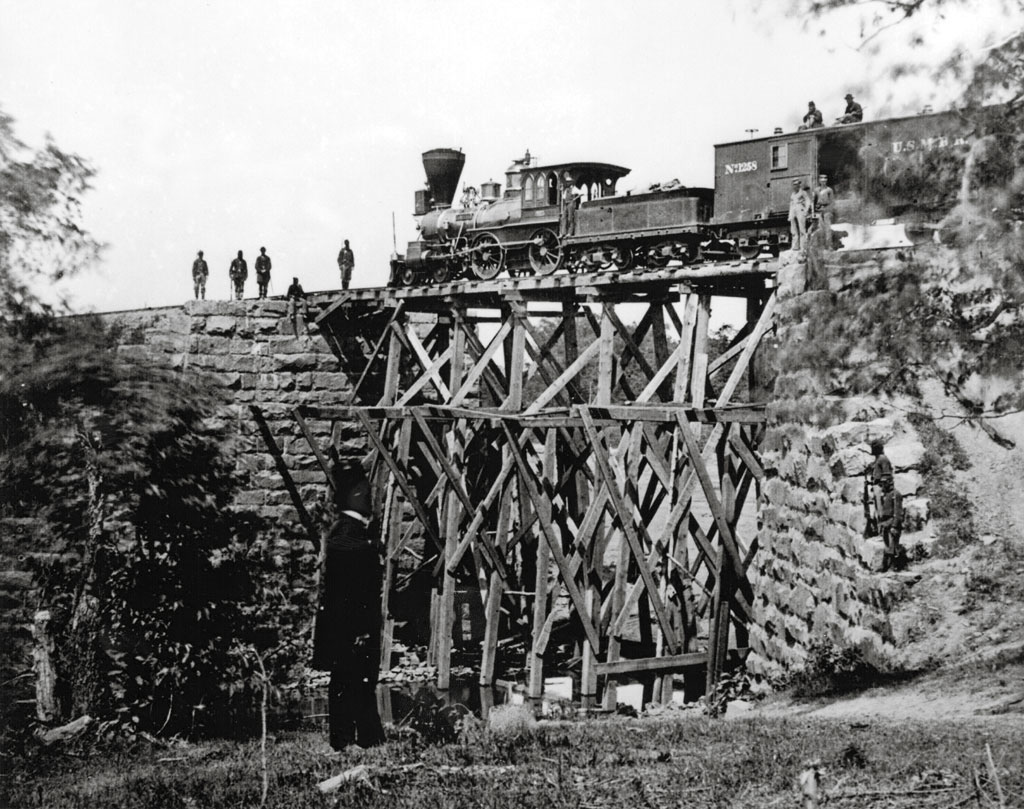

One of the most hotly contested railroad lines throughout the war was the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, which originated in Alexandria, Va. (across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C.), and ran south-southwest to Gordonsville, in Orange County. The northern end of the O&A was a combat zone from the time of “First Manassas” (the First Battle of Bull Run, in July, 1861) through the end of the war in early 1865.

This view (in photo above) is at Union Mills, Va., along the O&A just east of Manassas (and well within the perimeter of both Battles of Bull Run, which were all about control of the railroad). This is a temporary bridge across a creek flowing into Bull Run. It likely took United States Military Railroad Construction Corps personnel a day — two, at most — to build, using local trees and a mix of skilled and unskilled labor. Today it is the route of Norfolk Southern’s double-track main line between Washington and Atlanta.

It may have been wartime, but that didn’t mean locomotives couldn’t be striking machines. This is the nearly-new “J.H. Devereaux,” named after the superintendent of the U.S.M.R.R. at Alexandria, Va., just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. (and the site of the photo). It is an 1863 product of the New Jersey Locomotive & Machine Works.

With polished brass, polished iron, vivid red and blue paint, fancy lettering, and elaborate portraits of Devereux on the sand dome, the locomotive was the epitome of 1860s decoration. If this image were in color it would challenge our perception of Civil War railroading. It didn’t matter what its fate might be at the battlefront: Devereux was a respected and admired superintendent, and the locomotive bearing his name would engage the fight in handsome and colorful form.

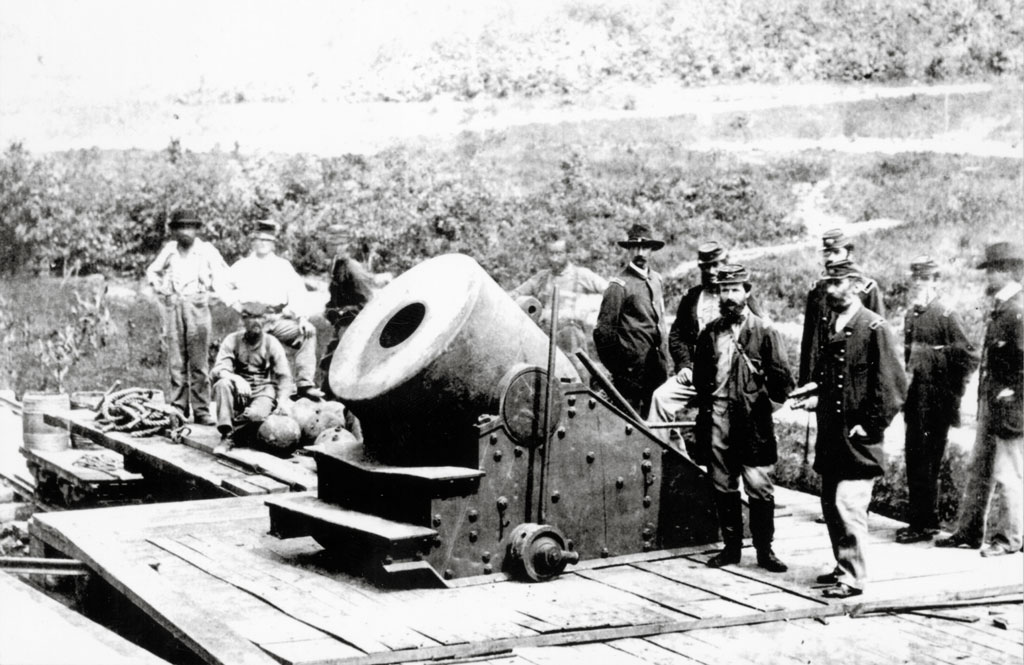

Some of the 12 men in this photograph (above) appear ghostly because of the time it took to make the exposure. We have no idea who they are, what roles they played, or what they thought of the war. This Union artillery crew was assigned to a uniquely powerful weapon: a heavy mortar nicknamed “The Dictator.” The idea was that the massive 200-pound explosive shells it hurled far behind Confederate lines would help “dictate” the terms of Southern surrender.

The technological might of the North — supported by its railroads — allowed the Union Army to imagine, design, cast, and transport this impressive weapon. The sophistication of the Union’s logistics network provided these men with an essentially unlimited supply of shells and powder, so that they could maintain a steady, deadly hail of destruction on the Southern defenders at the City of Petersburg. By the end of the war (in 1865, in Virginia), the conflict had lost its “honor” and devolved into a cold, hard, senseless war of attrition.

During the Civil War, Hanover Junction was the connection between the Hanover Branch Railroad — a local Pennsylvania carrier — and the Northern Central Railroad, which extended northward from Baltimore up the Susquehanna River Valley into central Pennsylvania. The Hanover Branch Railroad connected with another short line passing through the small Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg where, by chance in early July 1863, Lee’s Southern armies collided with Meade’s Northern forces. The Battle of Gettysburg was the “high point of the Confederacy” and the turning point of the War.

President Abraham Lincoln traveled by train to Gettysburg in November 1863. As the second speaker on the program to dedicate a National Cemetery for fallen Union soldiers, he gave his “Gettysburg Address,” one of the most stirring speeches in U.S. History. This may — or may not — be a photograph of Lincoln’s train returning to Washington from Gettysburg. But even if Lincoln is not on the platform (as some argue he is), this is Hanover Junction as he would have seen it.

In the field that meant repairing track and replacing bridges. But here at Chattanooga, at the end of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, that meant almost completely rebuilding the 151-mile-long railroad, and building a new railroad shop facility. The National Archives identifies this as the new Master Mechanic’s Office at Chattanooga. Note the re-purposed U.S.M.R.R. tender, the construction debris, and the presence of African American workers. They are most likely former slaves who were included in the Union war effort.

“The Dictator” was a standard 13-foot coastal mortar (designed to throw explosive shells at ships miles out to sea) repurposed as a “siege” weapon. Its objective was to throw exploding shells behind the earthen and masonry fortifications erected around the Virginia city of Petersburg.

Mounting it on a railroad platform car was an example of the innovation both sides practiced during the war. The mortar could be moved from place to place along the Union-controlled railroads outside Petersburg, so that the responding Confederate artillery could not accurately locate it. That general tactic persists to this day, and was a defining aspect of Cold War military planning. With a charge of roughly 14 pounds of gunpowder, the mortar could lob a 200-pound exploding shell roughly 11,000 feet and drop it behind Confederate fortifications, to devastating effect. The recoil pushed the mortar two feet back on its platform car and shoved the car itself another 10-15 feet back along the railroad.

A decade before the Civil War, the Western & Atlantic Railroad connected Chattanooga with Atlanta and the port cities of Charleston, Augusta, and Savannah. After 1861, the W&A was a lifeline for the Confederacy, linking the Upland South with the critical rail junction at Atlanta. That is why, in late 1863, the Union Army strove to take Chattanooga and establish it as the base for the push to Atlanta. It was one of the most critical moments of the war.

This was the Western & Atlantic’s main freight house in Chattanooga. The arched doors on each end allowed a train to “pull through.” The side doors allowed teamsters to back their wagons against the cars and workers to transload the freight. Even in the Deep South, and even during the Civil War, the elements of railroading and intermodal transportation were well understood.

We may think that the idea of a four-track, run-through freight car shop is a fairly recent idea. It is not. We have no real idea just how effective Civil War-era railroad operating and mechanical practice was. But we can at least be impressed by photographs such as this.

Daniel McCallum, the United States Military Railroad’s head, was an astute and expert railroader. He created a substantial and well-equipped railroad shop complex at Chattanooga in support of the Atlanta campaign and Sherman’s March to the Sea. In the same way that American shipyards erected Liberty Ships in WW II, the U.S.M.R.R. built and repaired freight cars to supply Union forces as they advanced through the South. Inside this unpainted rough pine building, Federal forces of all kinds — contractors, recruited railroaders, enlisted men, local labor, freed slaves — built and fixed the cars that supported 100,000 soldiers in the field.

The location is “City Point,” an arm of land where the Appomattox River separates from the James River, some miles to the east of the junction of the James River and the Chesapeake Bay. It is complicated Eastern tidewater, but it offered a way for the Union Army to supply its efforts to break the Confederate hold on the Confederate capital at Richmond, Va., and the City of Petersburg 20 miles south. The extensive rail-marine transfer facilities at City Point allowed the North to bring immense quantities of arms, supplies, food, and war material down the Chesapeake Bay and up the James River, where it could be transferred to freight trains to various battle fronts. Car ferries were an important link in that logistical chain.

The passenger car is typical for the 1860s and obviously used by the U.S.M.R.R. to transport troops and civilians as needed. The conical “Sibley Tents” were widely used by the Union Army to house troops. All around are the wharves, warehouses, and buildings used to supply the final push against Confederate forces, leading to the surrender of Lee’s army in April 1865.

Early in the war, Confederate forces adopted a “scorched earth” policy. Whenever they evacuated a position, they took pains to destroy whatever railroad facilities might be remotely useful to the Union cause. In 1862 at the northern Virginia railroad town of Manassas Junction, they laid waste. A year previous, this was a busy railroad junction between the Orange & Alexandria and the Manassas Gap Railroads. The junction had an engine house, machine shop, locomotive servicing facilities, and yard tracks. The remains of the turntable are prominent in the foreground.

The desolation represents the loss of property, which was soon replaced. But it strongly hints at the more profound loss of over 600,000 American lives. The American Civil War was the defining moment in our national experience. The Sesquicentennial of the Civil War is not an event to be celebrated, but to be mourned and regarded with regret and reflection. It was a war, which was both avoidable and inevitable. We have not yet come to grips with its consequences.

JOHN P. HANKEY is a historian who lives near Annapolis, Md.

Excellent, John.

As a native of Orange, Virginia, and being a very dedicated rail fan from a very early age, because of my father’s interest in railroads and history, on weekends we would walk along the old railroad grades left by the Southern Railway reconstruction of Washington Division after 1892. From the Rapidan River crossing north in to Culpeper County, the original Orange and Alexandria grade was located to the east of the new SR mainline. While, in the early 1950’s you could still see the old stone bridge abutments and piers as well as the shallow cuts and small fills of the O & A grades. We never found any artifacts or track parts that might have been left behind.

For several miles, a Virginia secondary route was built on the original O & A grade.

I read a book published 15 to 20 years ago that covered John Wilkes Booth’s attempt to escape Washington after he killed Abraham Lincoln and before he was cornered and killed in Caroline County, Virginia. It was suggested that he was headed to Orange Courthouse, Virginia so that he could get on an Orange and Alexandria train going south, deeper in to the old Confederacy.

That soon after the ending of hostilities and surrender at Appomattox, I have to question the reliability of any service that could have been provided by what was left of the O & A Railroad.

Brad Lee