Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe’s dock at Ferry Point outside of San Francisco burned May 4, 1984. I was on the job in 1984 and remember the fire vividly. The Santa Fe ceased tug-and-barge service across the San Francisco Bay shortly after.

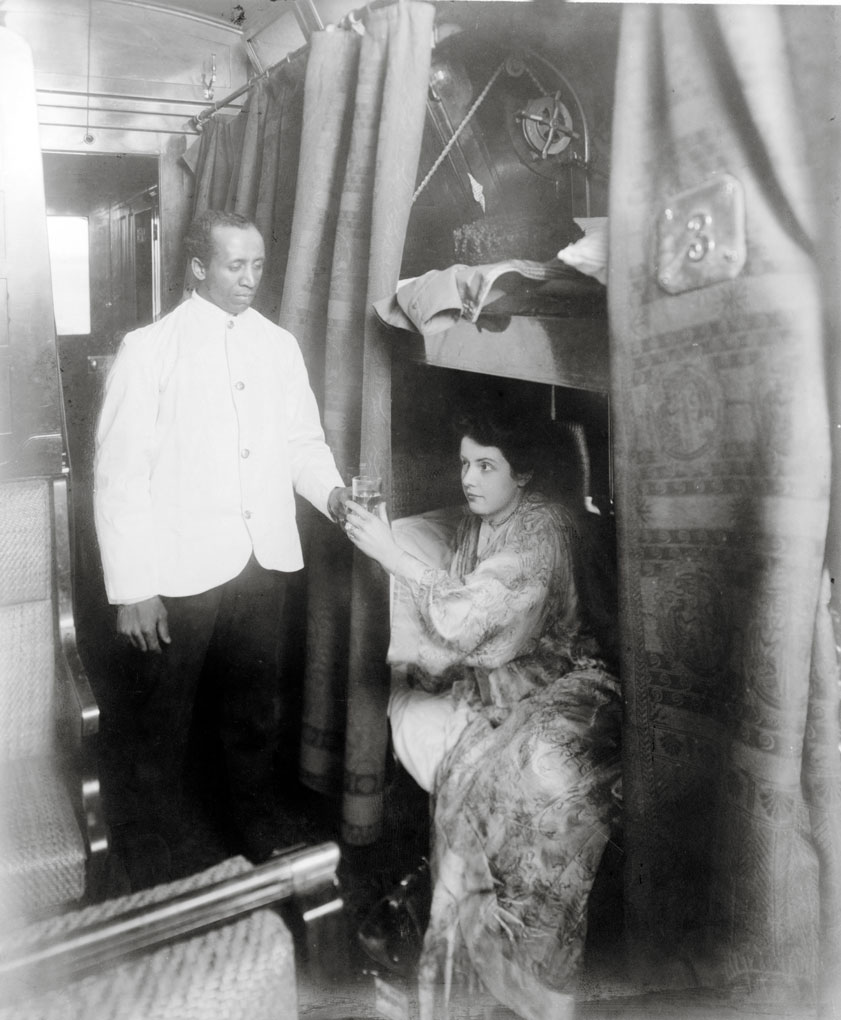

When I hired out in the mid-1970s, west end jobs were responsible for switching out inbound trains and servicing industrial zones in Richmond, principally around the deepwater shipping channel zones 3 and 4. These jobs also handled the traffic flow with our isolated yard in San Francisco, China Basin. Reaching this last yard required the intermediary use of a car float and tugboat, together referred to as “the barge.” Business in China Basin had been decreasing for years.

I worked the afternoon shift, with on-duty hours that ran from 3:59-11:59 p.m. Our first move involved pulling and spotting a large scrap yard in Zone 4. To get there entailed burrowing beneath Nicholl Knob through tunnel No. 5, ambling along the Bay, curving by Ferry Point, skirting the hills that fell down to the water’s edge, and finally entering a gate and into the metal company’s sprawling, ramshackle complex.

We gathered 20 or 30 loaded gondolas from the staging track in our yard, dragged them out to a runaround by the barge lead, cut off, then pulled a long string of empties from the scrap yard, left them on the lead, and shoved the loads back in.

“One of these days, they’re gonna keep the gons and torch them, too,” I mused, reflecting on the cars’ dilapidated condition.

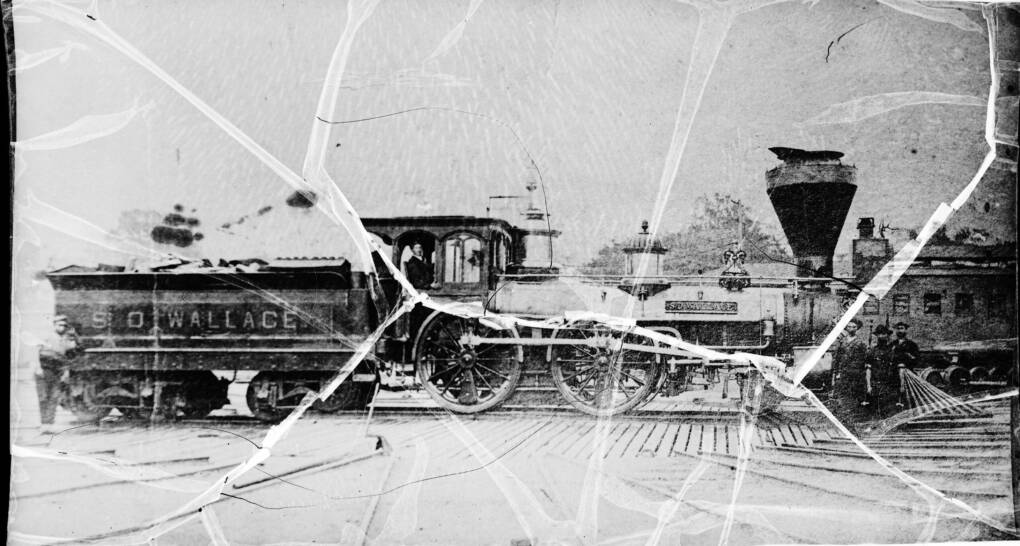

As the pin-puller, I threw the switches as we ran around empty cars on the barge lead. From my perch on the locomotive’s nose, I looked back and inspected Ferry Point in all its weed-choked, corroded glory. In its heyday, this facility was a key point on the Santa Fe system. Tugs, passenger ferries, and freight barges coursed to and from the city. There couldn’t have been a San Francisco Chief without it!

The slip had seen better days, but was still an impressive array of pilings, timbers, small buildings, a triple track squeezed onto a floating apron, and an overhead steel gantry topped with great wheels and cable — the kind seen looming above 19th century English coal mines. Everywhere, the slip had piles of old ties and broken pallets. Occasional fishermen and bums ignored “No Trespassing” signs. Coupled up and with air, our train trundled into the main yard.

Our next move sent us out again to Zone 4. The destination was a small tank farm adjacent to the ferry slip. The company distributed oils, like coconut oil and palm oil, to manufacturers of, among other items, shampoo. Our engine, an SW1200, had a comfy rear porch with plenty of room to sit back, put our feet up on the grab iron, and savor a rosy sunset on San Francisco Bay. We then exchanged loads for empties and poked back through the tunnel. The yardmaster contacted us via radio.

“Come on down to the shanty and get some coffee,” he said.

He might have added “and play pinochle,” but that was assumed. The shanty, a corrugated steel, utilitarian affair complete with pin-ups, ash trays, picnic tables, torn easy chairs, lockers, and a single restroom was our home away from home. As we arrived, out came the cards, thermoses, copies of Hot Rod, Guns & Ammo, and other male-oriented magazines.

Ricky, our hoghead, elected to spend his break in our engine. He was a family man and a devout Christian. The atmosphere in the shanty was a tad bachelor-like and pagan. I was unclear on how to play pinochle, so I watched for a while and then read an old paperback. The cards flew about as fast as the lies. The air was blue with cigarette smoke and bad language.

In a typical outburst of rudeness, the yardmaster’s Okie twang crackled over the squawk box, inviting the foreman outside to catch more dreaded “lists” chucked from the tower. Knowing my role, I clicked on my lantern and prepared to guide Ricky and our SW1200 out of the engine pocket.

I walked to the point of the engine. I gave signals, threw switches, and watched as we picked up the other crew members, their lanterns twinkling like fireflies at dusk. We lurched down track 9 to the west end bull switch. A sudden blast of our horn startled me and caused me to clench the grab iron, expecting a collision.

“The track is clear,” I thought. “What is Ricky trying to tell me?” I looked back. He was pointing straight ahead. I turned around.

“The barge is on fire!” Ricky yelled.

The blaze was so shocking, I was stunned and numb. The pulsing orange glow beyond Nicholl Knob had to come from Ferry Point. There wasn’t anything else in that precise direction.

Within seconds, the radio was alive with urgent talk. Sirens went off. I could smell burning creosote.

As I approached our locomotive, a radio was playing Don McLean’s “American Pie.” We both looked to the west end, to a second sunset beyond the tunnel. A distant, disembodied lantern gave the ahead signal. We went forward.

The fire designated the end for direct Santa Fe service to San Francisco. Even if the idler cars and locomotive assigned to China Basin had been shipped back to Richmond prior to the fire, it would have made no difference. The line was broken.

The last I saw it, the burned barge slip was dissolving in the fog and there was little reason for an engine to roll through tunnel 5, unless it was shoving mile-long cuts of flatcars. I will always remember Santa Fe’s barge fondly when they it was alive and with sadness at its demise.

Author Jeff Reynolds says the barge fire he witnessed evokes emotions similar to what he felt after former Beatles singer John Lennon was assassinated in 1980.