The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 15, 1865, sent a Civil War-battered country into 20 days of national mourning. At the center of it all was a black-draped train, slowly and sadly carrying the former commander in chief’s body from Washington, D.C. to his hometown of Springfield, Ill.

The U.S. rail network is no stranger to hosting presidential funeral trains before and after — the first for William Henry Harrison in 1841 and the most recent for George H.W. Bush in 2018. Yet none have ever reached the magnitude of grief that followed the Lincoln Funeral Train, dubbed The Lincoln Special.

Finalizing the final journey home

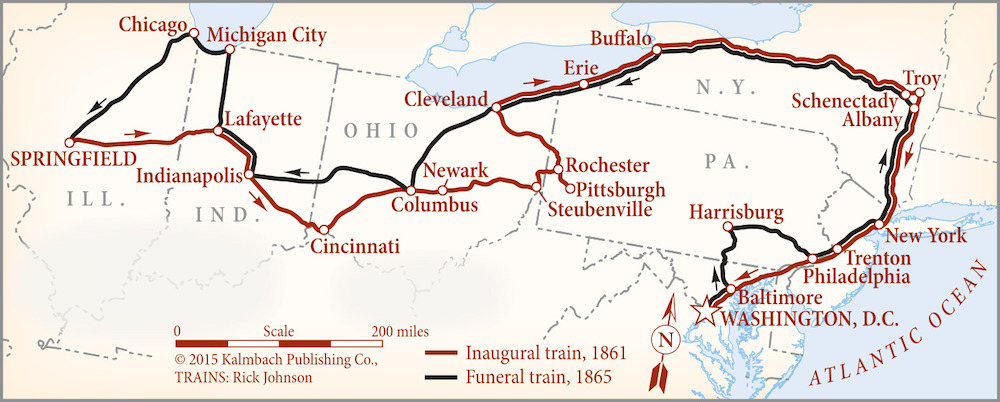

From its inception, plans for Lincoln’s funeral train route roughly retraced the trip the 16th President took for his 1861 inauguration. It wasn’t to the exact mile as a stop in Chicago was added for the city to host its own funeral. Meanwhile, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati were bypassed: The former due to an extra day that would’ve been added to the schedule and the latter raising concerns over sympathizers of the Confederacy. St. Louis even requested a visit from the train for the mourners west of the Mississippi River to pay their respects. The city was passed over as well.

After several days of lying in repose at the White House and lying in state at the U.S. Capitol, Lincoln’s coffin was placed on the train and left Washington on April 21. The journey covered 1,654 miles in 12 days. Due to the large number of mourners, the planned stops in Baltimore, Harrisburg, Pa., Philadelphia, New York City, Albany, N.Y., Buffalo, N.Y., Cleveland, Columbus, Ohio, Indianapolis, and Chicago included a funeral procession and ceremony at each city.

Burying Lincoln in Springfield seemed to be the obvious choice. But an agreement on the exact location of the burial site didn’t occur until the funeral train was already nearing Chicago. Former first lady Mary Todd Lincoln requested her husband be buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery on the outskirts of the state capital. Springfield officials proposed a grand tomb in downtown. The standoff between both parties ended with an ultimatum by the widow: Permanent interment would take place at the rural cemetery, or the body would instead be buried in Chicago. Oak Ridge was eventually chosen, and the train completed its journey to Springfield on May 3 for Lincoln’s final funeral and burial the following day.

A military train

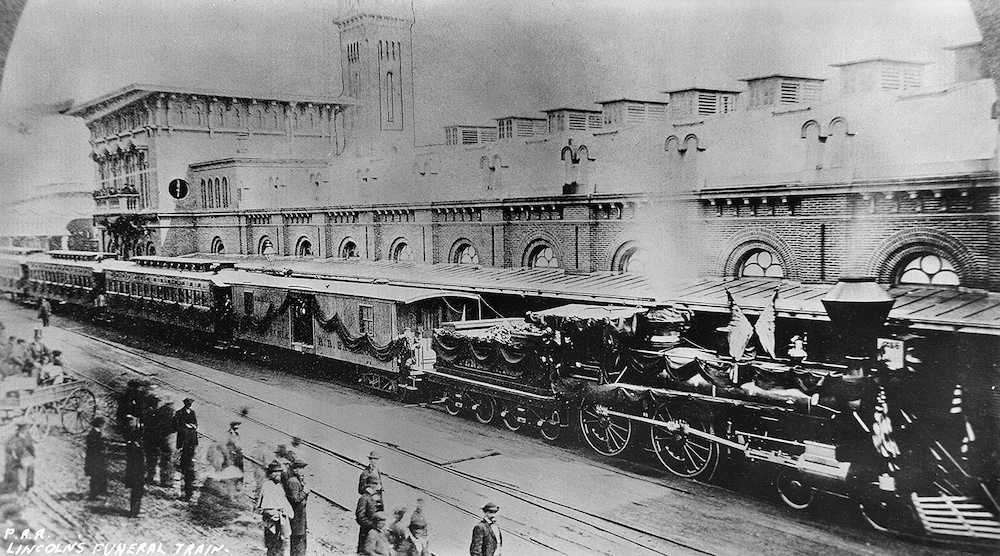

The special operated on over a dozen railroads, which were under the direct control of the U.S. War Department and Brig. Gen. Daniel C. McCallum. The top speed was 20 mph (5 mph through stations), and the train was given highest priority throughout the journey. Security was also exceedingly high with guards stationed at strategic points and switches spiked in place to guarantee a safe passage. Fresh from the Civil War and now a presidential assassination, no chances would be taken for what was a military train.

Nearly 42 steam locomotives and 80 passenger cars were used throughout the journey, with equipment changed between the traversed railroads. A pilot train of a single engine and car ran 10 minutes ahead of the Lincoln Funeral Train. The train itself consisted of one locomotive and nine to 12 cars – a baggage car, a mix of seven to 10 coaches and sleepers, the funeral car United States, and the officers’ car from the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad. Only the funeral and officers’ cars at the tail end made the entire Washington-Springfield trip.

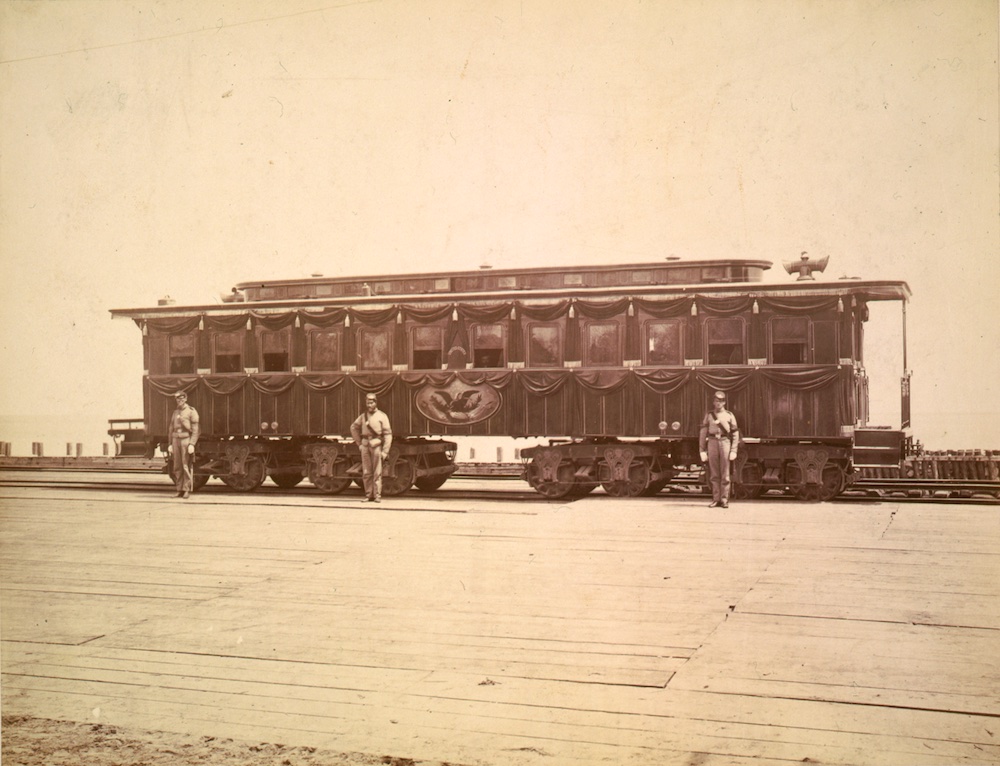

A funeral car built for a living President

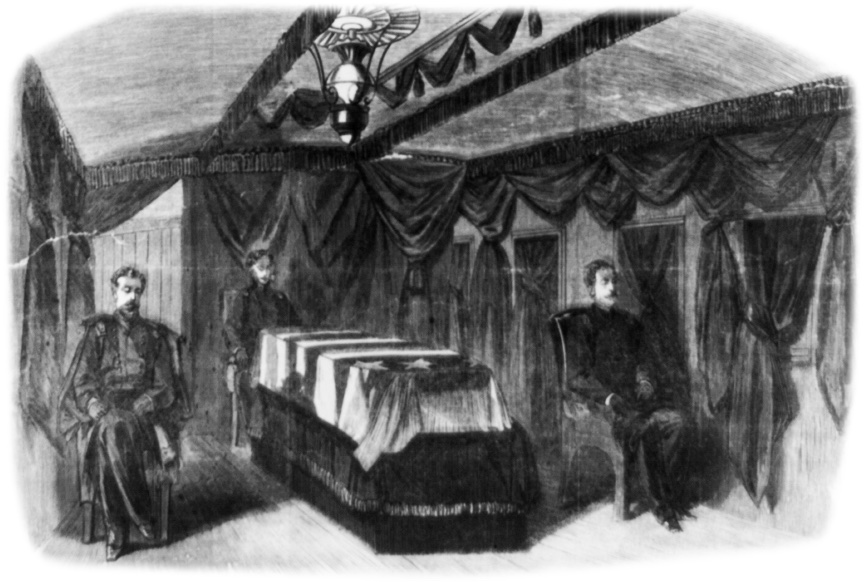

The lavish United States carried the coffins for both Lincoln and his 11-year-old son, Willie, who died in 1862. Built in 1865 by the U.S. Military Railroad, the parlor car was originally intended to be the equivalent of today’s Air Force One. A unique feature was the two sets of trucks at each end designed for smooth riding and easy conversion between standard gauge and 5-foot gauge track.

Lincoln had actually planned to visit the United States at the nearby Orange & Alexandria Railroad car shops on April 15, 1865. After his death that day, the car was immediately modified for funeral duty. Platform railings at one end were removed and rollers installed so the coffin could be moved in and out of the doorway with ease. After the funeral train, the car was sold to the Union Pacific Railroad before hopping between multiple owners. By 1911, the United States was destroyed in a Minnesota brush fire and the remains purged by collectors.

Who participated?

The train’s passenger capacity was about 300 people. Those who occupied it were mostly invited military, government, and railroad leaders, who boarded and disembarked at different stations along the route. An embalmer and undertaker accompanied the coffin, along with the honor guard and members of the family. A notable absence from the train was Mrs. Lincoln, who remained at the White House in mourning.

An estimated 1.5 million people viewed Lincoln’s body and over 7 million watched the train’s procession. Local timetables were made public while telegraphs along the route kept track of The Lincoln Special’s whereabouts. From major cities to the smallest village, night and day, mostly in the rain with little sunshine, people came out in masses to bid farewell to the president.

Leaving behind an historic memory

From books to a ballad, and from supernatural recollections to model and full-size recreations, the history of the Lincoln Funeral Train perseveres through the generations. While other U.S. presidents have been laid to rest with the aid of railroad conveyance, none equal the level of national mourning surrounding Lincoln’s somber procession across the eastern half of the country.

In many ways, it is the ultimate testament to Abraham Lincoln’s relationship with railroads. From a young lawyer representing the Chicago & Rock Island Railroad in the Mississippi River bridge case, to his advocacy for the Transcontinental Railroad, the 16th President’s vision for the growing nation placed railroads at the forefront. Although incredibly sad, to be carried home by rail was a fitting tribute.

A replica of the Locomotive also resides at David Abel’s Stone Gables Estate in Elizabethtown, PA just outside of Harrisburg. The ROW on David’s property is part of the original route of the Lincoln funeral train. My wife Bobbi and I have ridden the train with David a couple of years ago and will be back there this coming Christmas season. I would love to post a couple pictures of the Loco .