U.S. railroad electrification

In 1939, the United States was the global leader in railroad electrification, with over 20% of the world’s total. Today, electrification is a non-factor on almost all American railroads outside the Northeast Corridor.

How did this happen? The heady projects from the early 20th century that propelled the U.S. to world leader were built on predictions that their “white-coal” technology would replace steam power nationwide. Then came the Great Depression, World War II, and diesels. One by one, electric railroads switched off the juice and took down their wires. The last holdout, Conrail, quit mainline electric freight operations in 1981.

When oil prices spiked in 2008, American interest in rail electrification surged to a level not seen since the energy crisis of the 1970s. Industry managers and consultants began revisiting both the completed projects and stillborn proposals of decades past. In a July 2008 interview with Trains, BNSF Railway President Matt Rose confirmed that his company is studying electrification for its principal routes.

Norfolk Southern Chief Marketing Officer Donald W. Seale told the Journal of Commerce his company is exploring electrification as a byproduct of new high speed rail corridors.

Other Class I railroads are almost certainly doing the same, yet so far, none are stringing wires.

Meanwhile, Russia, China, and India are investing billions in freight railroad electrification and becoming the new world leaders. The recent dip in oil prices and downturn in traffic may have cooled some of electrification’s fervor, but other factors are emerging that could drive an American resurgence just as strongly as high oil prices … Scott Lothes

Trains Magazine brings you the story of America’s rise and fall as an electrification leader, and examines how new technologies and converging forces might jumpstart a new era of railroad electrification across the United States. Will overhead wires come to a main line near you?

Before you look to the future, however, it’s essential to understand the past. When it came to electrifying America’s railway, five distinct movements were the main technology drivers. Here’s a brief summary of each.

Original feature by Scott Lothes in November 2009 issue.

Tunnels

Mountains

Tunnel electrifications paved the way for larger projects, and soon a few lines tried much longer installations, including the coal-hauling Virginian Railway and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific.

Both the Virginian and the Milwaukee Road electrified their steepest mountain districts, where electrics held the greatest advantage over steam. The Virginian’s 134 miles of electrification, completed in 1925, included 14 arduous miles of 2 percent grade against loaded coal trains out of Mullens, W.Va. Taking a 5,500-ton coal train to the summit was a two-and-a-half- hour slog with a 2-8-8-2 road engine and two 2-10-10-2 pushers. Electric operation was an immediate success, as two 3-unit box-cab electrics whisked 6,050-ton coal trains to the summit in a single hour.

Ten years earlier, electric power similarly proved superior to steam in nearly every way when the Milwaukee Road energized 113 miles of its steep main line through western Montana. By fall 1919, the installation had grown to encompass two separate districts, a 438-mile division in the Rockies and a 207-mile district across Washington’s Cascade Mountains. Great Northern did the same for its route in the Cascades, running electrics through the Cascade Tunnel, the longest tunnel in North America at the time.

What killed the Virginian’s electrification was the line’s 1959 merger with the Norfolk & Western. The N&W was a much larger system and the Virginian’s 134 electrified miles were suddenly a much smaller portion of a larger whole, as well as an operating anomaly requiring specialized equipment that was confined to a limited area. The wires came down in 1962. (Ironically, N&W had electrified its own route through the Appalachians even before the Virginian, then forsook electricity for a diesel-powered line relocation.)

The situation on the Milwaukee Road was far more complex. Cash-strapped for much of its existence, the Milwaukee never made the major upgrades that would have been necessary to modernize its electrification, which had become quite outdated by the 1970s. The railroad’s directors had set their sites on merging with another railroad, and deferred maintenance across the system. In addition, the costs of maintaining separate locomotive fleets and servicing facilities for electric and diesel power became too much to justify. The wires came down in the 1970s, almost inexplicably during a global energy crisis that made diesels twice as expensive to operate.

Passenger terminals

Electrification expert William D. Middleton reports that in 1913, Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broad Street Station in Philadelphia was handling 500 daily trains. Even more remarkable was the fact that with terminal switching moves, each train required an average of eight movements through the interlocking plant, leading to a staggering 4,000 daily movements, nearly three every minute. Electrifying two of the busiest routes in 1913-1915 relieved much of the congestion, and it should be noted that unlike earlier projects, the PRR utilized A.C. in Philadelphia, which could easily be integrated into a larger system. The project was an immediate success. Electric multiple-unit trains, which could easily operate in both directions, eliminated the switching moves required by steam-hauled consists, while the trains’ faster acceleration cut the running time on 20-mile routes by as much as seven minutes.

Other railroads also electrified congested terminals and busy commuter lines, including the Reading Railroad in Philadelphia, New York’s Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station, the New York Central and New Haven commuter operations serving Grand Central Terminal, Illinois Central’s Chicago-area commuter service, and the Lackawanna’s commuter lines out of Hoboken Terminal.

Short lines

A handful of short lines have electrified most or all of their systems. By and large, these installations have proved successful. Black Mesa & Lake Powell, an isolated coal-hauler in northeast Arizona, is the poster child for this. The 78-mile railroad is well into its fourth decade of operating and has been entirely electric from its outset, using power from the generating station for which it hauls coal, rather than trucking millions of gallons of diesel fuel for hundreds of miles. Other coal-hauling railroads exist in Utah (Deseret-Western), Texas (TXU), and New Mexico (Navajo). Ohio’s Muskingum Electric, a well-known eastern example, ran two 12-car trains between a mine and a power plant from 1968 to 2002. The mine’s closing ended the operation.

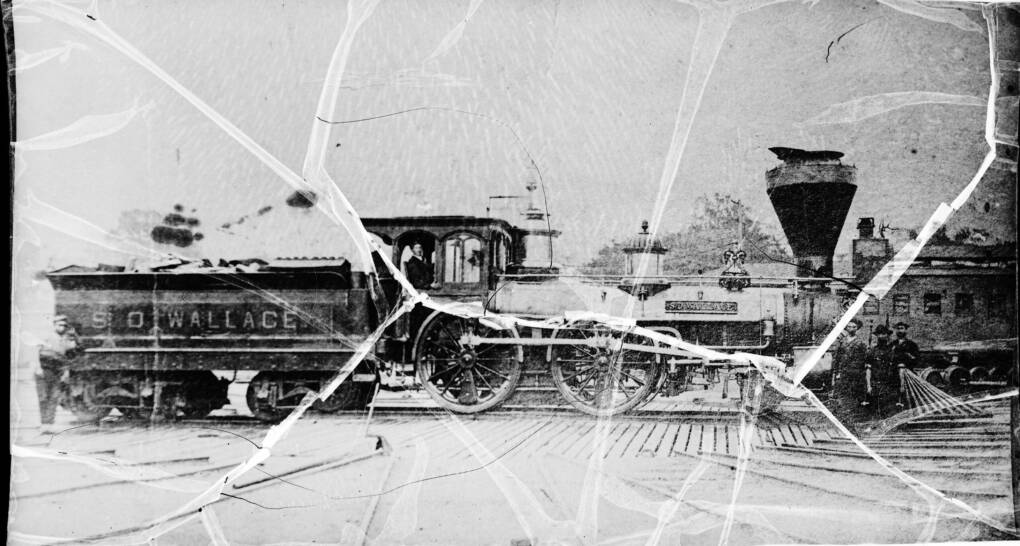

All of these lines owe a tip of the hat to the pioneer for this type of railroading: Montana’s Butte, Anaconda & Pacific. Its electrification in 1913 helped foster the Milwaukee Road’s subsequent installation. For more than half a century, BA&P operated a busy 26-mile electrified main line, hauling more than a dozen daily trains of copper ore. Only when a new smelter opened in Butte, eliminating the vast majority of the road’s traffic, did electric operations cease.

Trolley lines in Northeast PA (NEPA) were generally RR gauge, not trolley gauge. P&W (SEPTA Norristown HSL) is RR gauge They carried LVT’s cars between Norristown and 69th St. LVT connected with the NEPA lines. Neither P&W nor LVT carried carload freight but P&W connected with PRR for its own incoming loads as well as sand for on-line golf courses.

In NEPA proper, L&WV (Laurel Line) is RR gauge and carried carload freight in its own name as well as frequent passenger service between Wilkes-Barre and Scranton.

None of these was a “steam road”

Iowa Terminal is an electric line, an Interurban, rather than a “Steam” Road like the Rock Island.

This does leave anomalies! The Philadelphia & Western all think of as interurban but it was built under a steam road charter hence its gauge for PA. Iowa Term began as the Mason City & Clear Lake trolley line.

Too bad the considerable influence of US electric traction engineering in the world couldn’t be mentioned. In Europe there were until 1998 the Dutch and Spanish direct descendants of the PRR Westinghouse Rectifying locomotives and researching post WWII US electric traction manufacturing I’m only now discovering such GE and Westinghouse descendants in Chile, Brazil and Argentina.

I’m surprised that the Iowa Traction is not included in this article. It is still operating with trolley pole power.