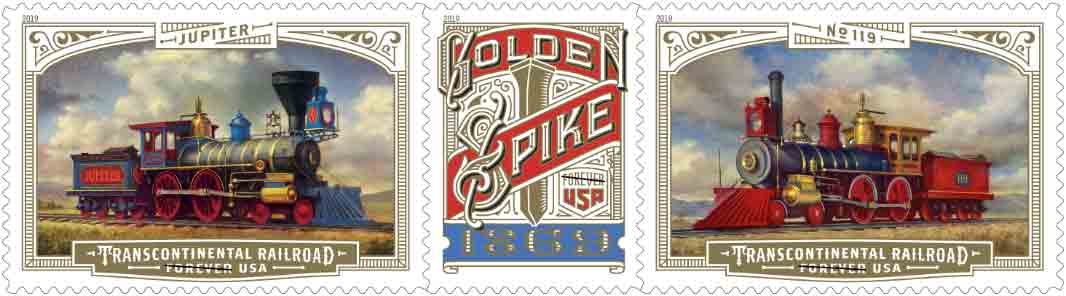

On May 10, 1869, the first Transcontinental Railroad was completed during the Golden Spike Ceremony. Yes, every rail enthusiast and elementary school student has this date ingrained in their mind. The rail enthusiast probably remembers the date better than the elementary school student, but nonetheless, it is a significant date in U.S. history. However, for all we know about the ceremonies surrounding the Union Pacific-Central Pacific meeting at Promontory, Utah, completing what had been an arduous struggle across the West, there are many details that are not common knowledge or have been confused for the past 155 years.

Come along as we peel back the years, looking into history, to discover five mind-blowing facts about the Transcontinental Railroad Golden Spike ceremony.

No. 1 — Why would the first national media event be preplanned?

Among the ceremonial objects brought to Promontory by Leland Stanford, Central Pacific Railroad president, was a silver-plated spike maul. The tool, manufactured by the Conroy & O’Connor Co., had been presented to the Central Pacific by San Francisco’s Pacific Express Co. During the ceremonies one telegraph wire was connected to the silver maul and another to the gold spike. When the two came in contact, a dot was sent across the country via the telegraph circuitry. This facet of the ceremony was preplanned. Every city with a fire-alarm telegraph was waiting for the signal as it activated the alarms. In New York and San Francisco, the telegraph wires had been connected to cannons, which fired out over the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, upon receiving the telegraphic message.

The bulk of the ceremony, however, was left unplanned. That’s right — most of what happened at Promontory on May 10, was determined shortly before the program happened that day. When the UP and CP parties both arrived, deciding what would happen, by who and in what order was left to the UP’s Grenville Dodge, chief engineer, and CP’s Edgar Mills, a Sacramento banker. Mills served as master of ceremonies. Dodge gave remarks on behalf of the UP.

In the most primitive manner, the Golden Spike Ceremony was the first nationally broadcast media event. Thousands of telegraph stations across the United States simultaneously received the maul taps and other keyed messages from Promontory. Despite the significance of the occasion and knowing that the date was coming, at least a month in advance, little to no forethought was given to the events of the day. In contrast, 155 years later, media events on a national level are highly choreographed and planned well in advance.

No. 2 — The gold nugget on the gold spike

During the May 10th ceremony four commemorative spikes were presented:

- one made from 18 ounces of pure gold from David Hewes, a San Francisco contractor;

- another of silver presented by F.A. Tritle of Nevada;

- one made of iron, gold, and silver gifted by Gov. Safford of Arizona;

- and, a second gold spike ordered by Frederick Marriott, owner of the San Francisco News Letter.

The Hewes gold spike had a rather large rough gold nugget attached to the pointed end. Hewes removed the nugget shortly before the ceremonies, and later had it melted down and fashioned into small rings and watch fobs. The rings were presented to Leland Stanford, Oliver Ames, UP president, President U.S. Grant, and Secretary of State William H. Seward. The watch fobs were gifted to a number of unidentified dignitaries and relatives of Hewes.

If a particular Transcontinental Railroad history is detailed enough the rings will be mentioned, however, rarely are the watch fobs included in the story.

No. 3 — Take a swing

While portions of the Golden Spike Ceremony have been distorted or told with varying details, the driving of the last spike has countless variations. There are number of details that are known and consistent about this aspect of the event.

Despite descriptions of mighty blows being struck to drive the gold spike, we know this is not true. Gold is a soft metal, and the spike would have been destroyed if a full-force swing had been taken. Additionally, photographs of the gold spike show four small indentations in the head, leading to the conclusion that it was tapped in, not driven. The laurel-wood tie also had pre-drilled holes, eliminating the need for “driving” in the gold spike.

Some accounts indicate that an unidentified young lady was given the honor of the first swing. In this case, it is reported that she missed, yielding to Stanford and UP Vice President Thomas Durant. Other descriptions state that Stanford took a position by the south rail with Durant on the north rail. Both swung, missed, and were replaced by the UP’s Dodge and Samuel S. Montague, the CP’s chief engineer, who together finished the task. Still other accounts indicate that Dodge and Montague both failed to drive the last spike home, leaving the task to unidentified track workers from both railroads.

There are several reasons for the varying accounts. By this point in the event, the crowd of approximately 1,000 had pushed forward encircling the meeting point. Only a few people had an unencumbered view. Some of those writing reports, guessed at what transpired. Other accounts were written second-hand by people who weren’t even present at Promontory. The ensuing historical “telephone” game has distorted the event’s details.

No. 4 — Union Pacific who?

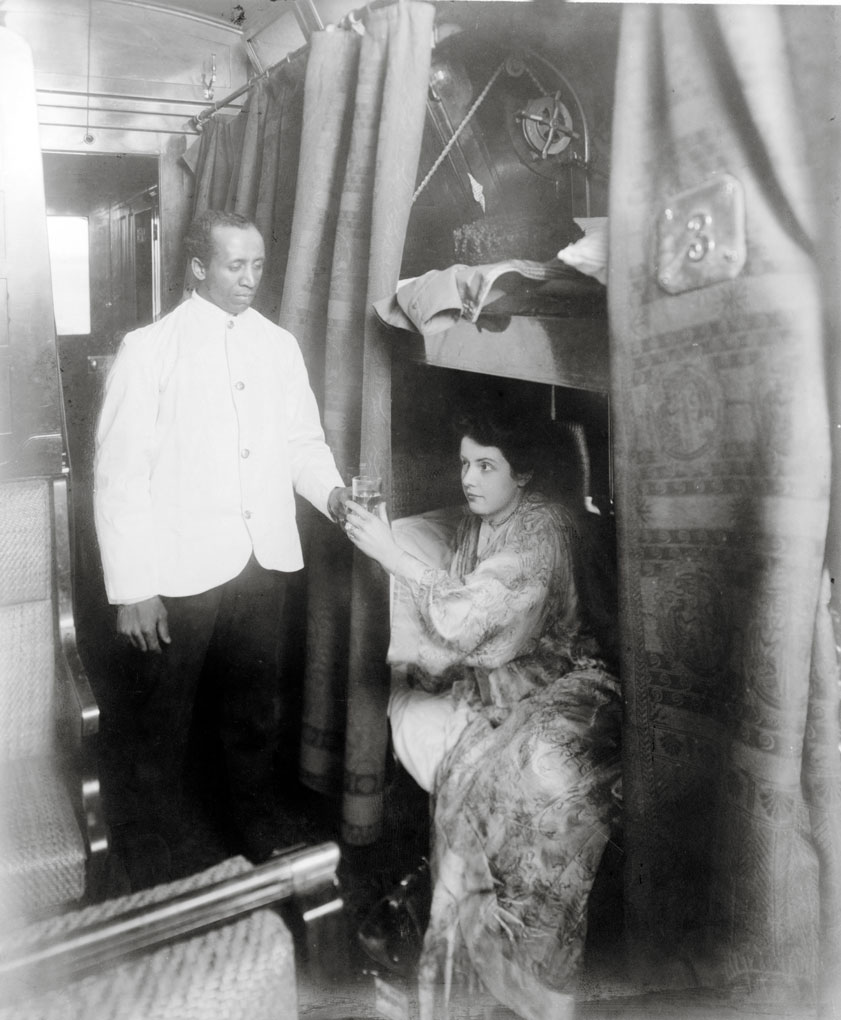

One fact that is not disputed regarding the May 10th festivities is the fact that some significantly large egos came with the VIPs — particularly Stanford and Durant — and the Central Pacific, as a whole. Notice that all of the ceremonial gifts — the spikes, the spike maul, and “last” tie — all came from friends of the Central Pacific, were inscribed for the Central Pacific, and were presented to Stanford, as Central Pacific president. History offers a few reasons for this lack of Union Pacific recognition.

Although the UP laid more track, starting in Omaha, Neb., its senior management was located in New York and Boston — much farther away from the railroad than the CP with headquarters in Sacramento, Calif. Oliver Ames, UP president, was not present at Promontory. Durant was the senior UP official present. Throughout the UP’s construction Durant had managed to offend just about everyone with his financial slight-of-hand, legal bullying, and self-indulgence at the company’s expense. While Durant had a huge ego, Stanford’s was bigger.

A prime example of the egotistical, prima-donna-ish atmosphere brought to Promontory by Durant and Stanford lies in the trackside program planning on May 10th. Some historical accounts have Durant, Stanford, or both storming to their private railcars in fits of pique, feeling they had been slighted in some manner. Based on gifts, position in the program, and length of address, Stanford and the Central Pacific won the ego battle over Durant and the Union Pacific.

Footnote … One excuse offered for Durant’s behavior at Promontory is that he was suffering from a blinding migraine headache. While this may be true, it has also been reported that he drank to excess the previous evening, leaving him cranky and hungover.

No. 5 — Return it … with your compliments

Brothers Jack and Dan Casement, who managed the UP construction crew, joined in the celebration at Promontory following the formal ceremonies. Historical accounts have them dining and drinking in the private cars of both Durant and Stanford. As noted by Grenville Dodge, the festivities aboard Stanford’s car took an unexpected twist. Stanford rose and began, according to Dodge, “a severe attack upon the Government. He went so far as to claim that the subsidy, instead of being a benefit, had rather been a detriment, with the conditions they had placed upon it.” The federal government heavily supported the construction with bond issues and land grants, which were essential to the railroad’s completion. In the midst of Stanford’s tirade, Dan Casement climbed on his brother’s shoulders and the two began parading around the car. From his elevated position, Dan exclaimed, “Mr. President of the Central Pacific: If this subsidy has been such a detriment to the building of these roads, I move you, sir, that it be returned to the United States Government with our compliments!”

Casement’s proclamation brought a great cheer from those assembled and much laughter at the expense of the less-than-sober Stanford. Dodge finished his report of the incident: “[It] put a very wet blanket over the rest of the time.”

Now it’s your turn to discover five more mind-blowing facts about the Golden Spike and the Transcontinental Railroad. Thousands of pages have been written on the subject, each relating the story from a slightly different perspective. To start you on your Transcontinental Railroad journey, here are a few links from Trains.com:

- Transcontinental Railroad: Building track

- Tracklayers reach incredible goals on the transcontinental railroad — Part 1

- Tracklayers reach incredible goals on the transcontinental railroad — Part 2

- The History of the Transcontinental Railroad

Good article. Just a few corrections.

In No. 1 – The company that presented the silver (plated) spike maul was the Pacific Union Express Company. See my article in Trains, May 2019, p 27.

Also, photos show that the telegraph wire was attached to the rail, not the Golden Spike – the spike was sitting in an augured hole, so its head rested on the rail, and provided electrical connection when the spike maul tapped (not struck) the spike head. Trains, May 2019, p 27.

No. 2 – I believe the gold sprue (“nugget”) from the Hewes spike was removed at Promontory (thus tales of the Hewes spike being cut in half). Hewes himself was not at Promontory, so Stanford had the sprue removed shortly before the ceremony, and later returned it (or half of it) to Hewes. Both Hewes and Stanford had commemorative tokens (rings and watch fobs) made from their portions of the sprue. Hewes actually had two spikes cast, only one of which was engraved before the ceremony and sent to Promontory. Hewes kept the second spike in San Francisco, and had it engraved after the ceremony. Today it is on display at the California State Railroad Museum, with its sprue still attached.

No. 3 – The Golden Spike was certainly not “driven”, this article correctly describes the “taps” on the head during the ceremony. To my knowledge, there has never been any serious investigation whether the small indentations in the spike head today might have been caused by erosion from the electrical arc and spark when the spike was tapped. Other possibilities are the physical strike of the hammer (although why would a flat faced hammer would leave a rounded dent?), or that military officers present tapped the spike with the hilt of their swords, likely with rather more force from the weighted, rounded pommels.

As to actually swinging at spikes, after the ceremony there were several adjacent ties that did not have spikes. Spikes were started by track workers, and “dignitaries” were allowed to take swings (with strikes or misses depending on the skill, or luck, of the person swinging.)

No. 4 – It is worth noting that ALL the items used in the ceremony – all 4 spikes, tie, hammer – had been provided by others, and not by the Central Pacific itself. There are also a couple of passing mentions that the Union Pacific “might” have brought an iron Last Tie – if so, it clearly was not used, but it also does not have the historical trail that the items the Central Pacific brought have, so may never have existed.

After the ceremony both the Hewes Golden Spike and the Nevada Silver Spike were returned to the people who provided them. The Nevada spike had been rushed to Promontory unfinished. Tritle had it polished and engraved, and then presented it to Gov. Stanford in a beautiful wooden case. Stanford returned the Golden Spike to Hewes upon his return to California. Hewes kept it until 1892, when he donated his art collection to Stanford University, and the spike along with the art. The second Hewes spike remained in the family until 2005, when the California State Railroad Museum acquired it from Hewes heirs. We know that the Arizona spike was given (presumably by Safford, who was at Promontory) to Sidney Dillon, a member of the board of directors of the Union Pacific who was also at Promontory. We suspect that the San Francisco News Letter Golden Spike was given to John Duff, another member of the board of directors of the Union Pacific who was also at Promontory, but that has not yet been proven. So far as we know, Marriott was not at Promontory, so it is unclear when and how he may have given his spike away. Both Dillon and Duff can be seen holding up spikes in several photos taken after the ceremony at Promontory.

Ultimately, the Last Tie was in the Southern Pacific headquarters in San Francisco, and burned with the building in the 1906 Earthquake & Fire. Today the Hewes Golden Spike, the Nevada silver Spike, and the silver plated spike maul are all at Stanford University. the Arizona spike was given to the Museum of the City of New York in the 1940s by Sidney Dillon’s granddaughter. In 2023 the museum de-accessioned the spike and auctioned it off as a fund raiser – it was purchased by a private collector. A private collector in New England has what is suspected to be the San Francisco News Letter spike. He purchased it years ago from a dealer in Maine, but that dealer had no background information on where the spike originally came from.

As to the “track gap” near Omaha across the Missouri River – it was filled by a ferry in the summer, and by laying track on the ice in the winter. The bridge connecting Omaha and Council Bluffs opened in 1872. the Tirst Missouri River bridge, near Kansas City, opened in 1870.

Good one! For all we know the DeMille version may be the true one. Oh–there still was a track gap near Omaha which wasn’t closed for a few years.