Many railroads have had their share of drama and intrigue, but it is hard to recall another railroad with the narrative complexity and heroic scale of early Union Pacific. And UP’s creators envisioned it as a truly national project, with stewardship of the railroad shared broadly and managed for the overall good of the entire country. Theirs was a sincere, altruistic, and utterly naive vision for a great national highway.

The Pacific Railroad Act

In summer 1862, Nearly 80 commissioners assembled in Chicago, along with dignitaries, journalists, and other interested parties gathered in Chicago in late August. They were at the country’s emerging railroad hub for the first meeting of the Board of Commissioners of the Union Pacific Railroad and Telegraph Co.

The legislation President Abraham Lincoln signed two months earlier could not have been more direct. The text of the Pacific Railroad Act began with the names of 156 prominent Americans from every state in the Union (except, oddly, Delaware). Proponents wanted everyone to understand the legislation was non-partisan, broadly supported, and that the railroad it authorized was a truly collective effort. It was not to be regarded as the special project of a particular region or interests.

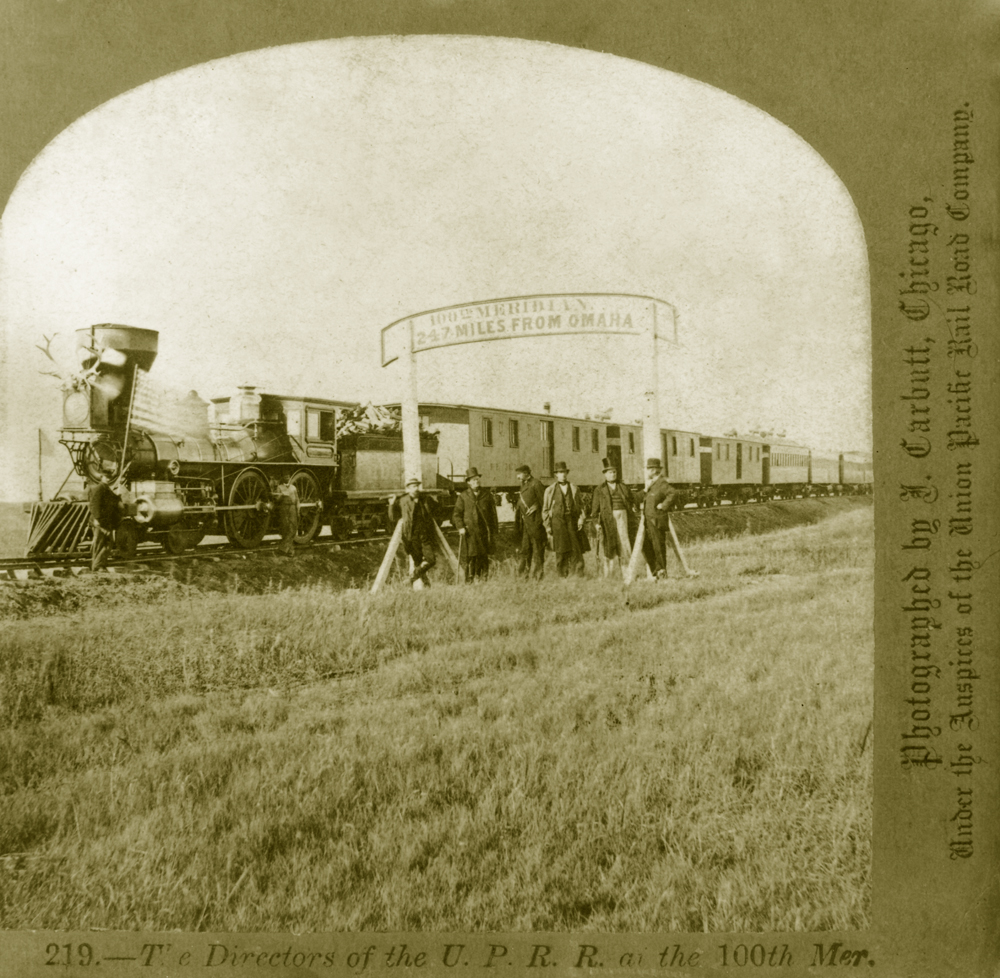

During three days in early September, the commission convened to discuss implementing the objectives and requirements laid out in the Pacific Railroad Act. The commissioners elected Chicago Mayor William B. Ogden chairman, and Henry Varnum Poor, editor of the American Railroad Journal, as secretary.

Whether it was subtle propaganda or sincere belief, the participants stated that a railroad to the Pacific Coast was a matter of great urgency and national defense. The Confederacy was seeking diplomatic recognition by Great Britain during the worst days for the Union during the American Civil War. Some suggested Great Britain might try to “peel off” the new state of Oregon, or that the Confederacy might make a play for California.

Economic arguments for the Pacific Railroad still made sense, though.

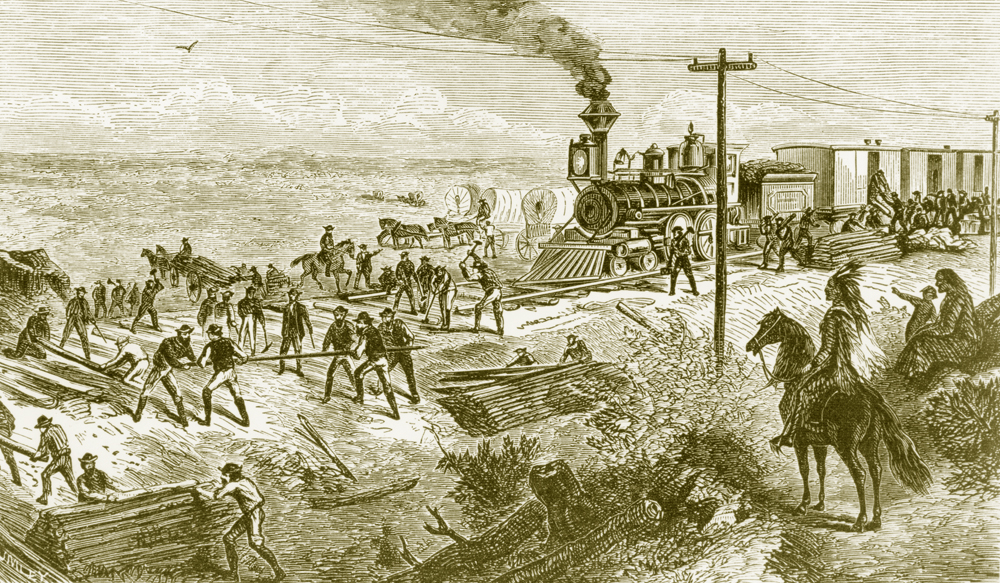

The engineering remained sound, and the North clearly had the resources to complete 1,800 miles of additional track. What had changed by summer 1862 was the conviction that a transcontinental railroad was needed sooner rather than later.

The only way to make that happen in the middle of a Civil War was to define the Pacific Railroad as a national priority with widely shared benefits, and then harness private entrepreneurial energy and naked self-interest — strangely missing until the 1860s.

The US commitment to Manifest Destiny

By the time Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act, the idea of a railroad to the West Coast had been in circulation for almost 30 years. Asa Whitney, a New England merchant and traveler, began advocating for a Pacific Railroad in 1845. The route he favored ultimately became the Northern Pacific.

Whitney recognized a transcontinental railroad would open the vast U.S. interior for development and connect it to ports on both coasts. It would also create a shorter, faster cross-country route for commerce between Europe and Asia.

With the rise of oceangoing steam navigation in the 1840s, Morse’s demonstration of the magnetic telegraph in 1844, and an astute understanding of economic trends, he understood the potential for industrialization, large-scale agriculture, and expanded international trade.

Whitney was proposing a global economy similar to ours today, with the U.S. at the center and railroads as high-speed conduits.

But the country wasn’t ready. There were too many railroads to build in more populated areas.

Gold had not yet been discovered in California. Rails had barely reached the Mississippi River. And at the same time, the question of slavery loomed ever larger in American politics. Even so, there was active discussion of a Pacific Railroad throughout the antebellum period.

In 1853, Congress appropriated $150,000 (between $50 million and $75 million today) for a comprehensive railroad survey from the Midwest to the Pacific Coast. Army topographical engineers surveyed five different routes: one Central, one Northern, two Southern, and one along the California coast. They did not survey the route ultimately followed by the Union and Central Pacific railroads because it was already reasonably well known.

The surveying took two years, and assembling 12 volumes of findings took almost five (1855 through 1860). The result was the first systematic study of large areas of the Western U.S., and descriptions of three feasible transcontinental railroad lines. Railroads built all of those lines eventually. But it took the secession of the Southern states to push the U.S. government to build the initial Pacific Railroad.

Interested in learning more about the history of the Transcontinental Railroad? You’ll find it in our special issue, available online.

great history and look forward to May issue, I did get my copy of Journey to Promontory and will be there with friends for the festivities.