Removing the Transcontinental Railroad’s last spike

The weather was warm and mild on Sept. 8, 1942. An automobile caravan, headed by Utah Gov. Herbert Maw and a police escort, departed from Salt Lake City early that morning. Stops were made at Clearfield and Ogden, Utah, to pick up representatives from the U.S. Navy and Southern Pacific. While in Ogden, Maw took part in a special program about the unspiking ceremony that was broadcast over radio station KLO.

The ceremony, of course, was a tip of the hat to the Transcontinental Railroad’s golden spike moment at Promontory that happened some 73 years earlier.

The Utah governor’s caravan then continued to Brigham City, Corinne, and past Promontory to Rozel, where Everett B. Michaels, vice president of Hyman-Michaels a construction company, treated 88 guests to a chicken dinner with all the trimmings served under the direction of camp manager Jack Carson.

Afterwards, the caravan traveled back the 8 miles to Promontory.

Recreating the ceremony at Promontory, Utah

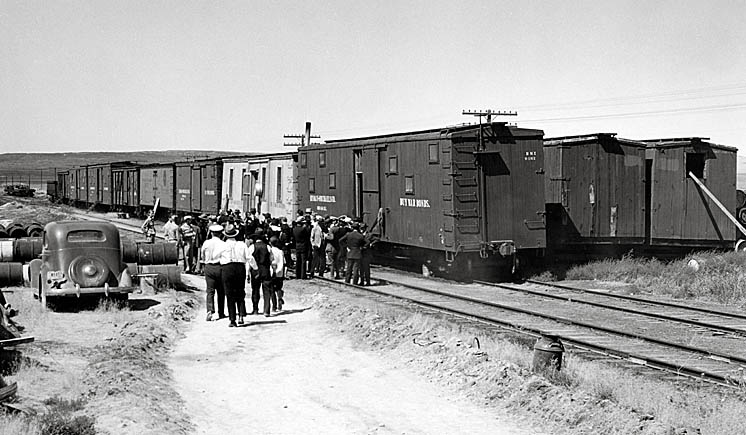

To re-create the 1869 ceremony, Hyman-Michaels’ two locomotives were positioned facing each other at the obelisk monument that had been erected decades earlier to mark the Last Spike location. A crowd of about 300 persons witnessed the unspiking — about half of the estimated 600 that attended in 1869.

Frank Francis, columnist for the Ogden Standard-Examiner, was master of ceremonies for the event, which started at 2 p.m. and lasted 30 minutes. George Albert Smith, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, gave the invocation. Removal of the “Last Spike” then commenced. Newspapers reported that Mrs. Ralph Talbot Jr., wife of the commanding officer of the quartermaster depot in Utah (and whose great-uncle had attended the 1869 event), presented Maw with a claw bar. Maw used it to raise the spike an inch from its position in the tie, followed in succession by E. C. Schmidt, assistant to the president of the Union Pacific; SP Division Superintendent L. P. Hopkins; and Everett B. Michaels, who removed the spike as the crowd cheered.

Two people present in 1869 were present for the unspiking ceremony

With the driving of the Golden Spike having occurred only 73 years earlier, there were two attendees in 1942 that had been present at the original ceremony. One was 85-year-old Mary Ipsen of Bear River City, Utah, who at age 12 had been a cook’s helper at Promontory on May 10, 1869. Ipsen reminisced that she “got to eat whatever was left over after the construction workers had gotten their fill.”

The other was Israel Hunsaker, then 90, who’d been a track worker on the line and helped to lay the rails over Promontory Summit. He was reported to have attended the “Wedding of the Rails” and appears in A. J. Russell’s famous “champagne photo” [page 4] as a young man in the front row, fourth from right, although some historians dispute this claim.

Other participants with ties to the first event included William C. Warner, then 86 years old, who, as the SP’s oldest pensioner, started work for the Central Pacific in 1870. Cora R. Gibbs also attended; her father, Edgar Stone, claimed to have been the engineer on CP’s Jupiter 4-4-0 steam locomotive. (There has been debate over whether Stone or another person, George Lashus, was engineer of the Jupiter at the ceremony; other records show the engineer as being George Booth.)

Following the unspiking, visitors and dignitaries quickly departed, and the scrappers wasted no time in getting back to the task at hand. Photographs suggest the scrap gang made short work of tearing up the main track upon which the ceremony had just been held, with some area residents who attended the event lingering to watch the rails be removed.

What happened to the rails and spike saved from the Transcontinental Railroad ceremony?

The 1942 ceremony resulted in several relics from the occasion, some now clouded in mystery. Following the unspiking, the spike SP prepared for the event was presented to the Daughters of Utah Pioneers, and was exhibited for a time at the Utah State Capitol in Salt Lake City. However, its current whereabouts are unknown.

A small, rusty iron spike removed from a cross tie, which supposedly occupied the same position as the original one into which the Golden Spike had been driven, was presented to Brigadier General Ralph Talbot Jr., by E. G. Schmit of the Union Pacific. The spike was later included in a glass-covered display that eventually wound up in a back room at the quartermaster depot at Ogden, largely forgotten until it was rediscovered years later. Unfortunately, with all witnesses deceased, there is no way to confirm its authenticity.

The two rails that corresponded to the position of the last two rails originally laid in 1869 were donated to officials from Brigham City and Ogden, respectively. While the section that went to Ogden has been lost, disposition of the rail given to Brigham City is readily known, since members of the Box Elder Junior Chamber of Commerce were determined that Brigham City would remember the day that it was un-spiked. In December 1943, a marble marker incorporating the rail was dedicated in a public ceremony at the southwest corner of the Box Elder County Courthouse. Today it’s displayed near Brigham City’s former UP depot.

It took Hyman-Michaels another month after the un-driving ceremony to complete the removal of the Promontory Branch, working at a rate of up to three miles per day. Its contribution to World War II was significant; the U.S. Navy used the rail to build sidings and spurs at Utah’s Clearfield Navy Supply Depot and at the Army’s Defense Depot Ogden Utah — both major hubs of activity during the war. Some of it was also reportedly used at the arsenal at Hawthorne, Nev. At 120 miles, the Promontory Branch was the longest single line abandonment in the U.S. during 1942.

With its rail line now history, many predicted that the future for Promontory was bleak. Although the obelisk monument remained by the abandoned right of way, there were precious few reminders of the historical event that had occurred there. There were seldom any visitors, as it was a long drive along a rough dirt road to reach the location.

More Transcontinental Railroad last spike ceremony recreations

In the next two decades a few scattered events were held to celebrate the driving of the Golden Spike, most notably in 1949 when railroad enthusiasts Lucius Beebe and Charles Clegg re-enacted the ceremony at Promontory, but most of the anniversaries were held at Corinne, Utah, a much easier location to reach. In the 1950s the Sons of Utah Pioneers opened the Railroad Village Museum in Corinne, with two early 1900s-era steam locomotives situated face-to-face in the “Promontory pose.”

For one local resident, Bernice Anderson, simply looking at old pictures and old engines in a museum wasn’t enough. She wanted the site of the Golden Spike to be saved and recognized, and after many years of lobbying, the National Park Service created the Golden Spike National Historic Site in time for Promontory’s 100th anniversary in 1969. Ten years later, in 1979, replicas of Union Pacific’s No. 119 and Central Pacific’s Jupiter were built and are used today for re-enactments.

In a span of 73 years, Promontory went from being the historic location of the completion of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad to a siding on a secondary branch line to an abandoned right-of-way with only a stone monument remaining to mark the ceremony that joined the nation. It can be debated whether or not the events that took place at Promontory in 1942 nearly destroyed a major part of American history under the guise of patriotism, but fortunately, because of preservation efforts over the past five decades, Promontory is now recognized for its role in American history and serves as living reminder of the events that took place 150 years ago.

Want to find out more about the Transcontinental Railroad?

Facts, figures, history, and more are available from our special Journey to Promontory magazine, available at our partner shop, the Kalmbach Hobby Store.