Barriger III (1899-1976) rose to national prominence in the railroad world during the late 1920s and the early 1930s, first as a bureaucrat and, after World War II (1941-45), then as a railroad president for four different lines (the Monon, Pittsburgh & Lake Erie, Missouri-Kansas-Texas, and the Boston & Maine). He was most active as a photographer in the 1930s, but he made pictures throughout his six-decade career in the industry. “He was never without his camera,” according to his son, John Walker “Jack” Barriger IV.

Reconstruction Finance Corporation

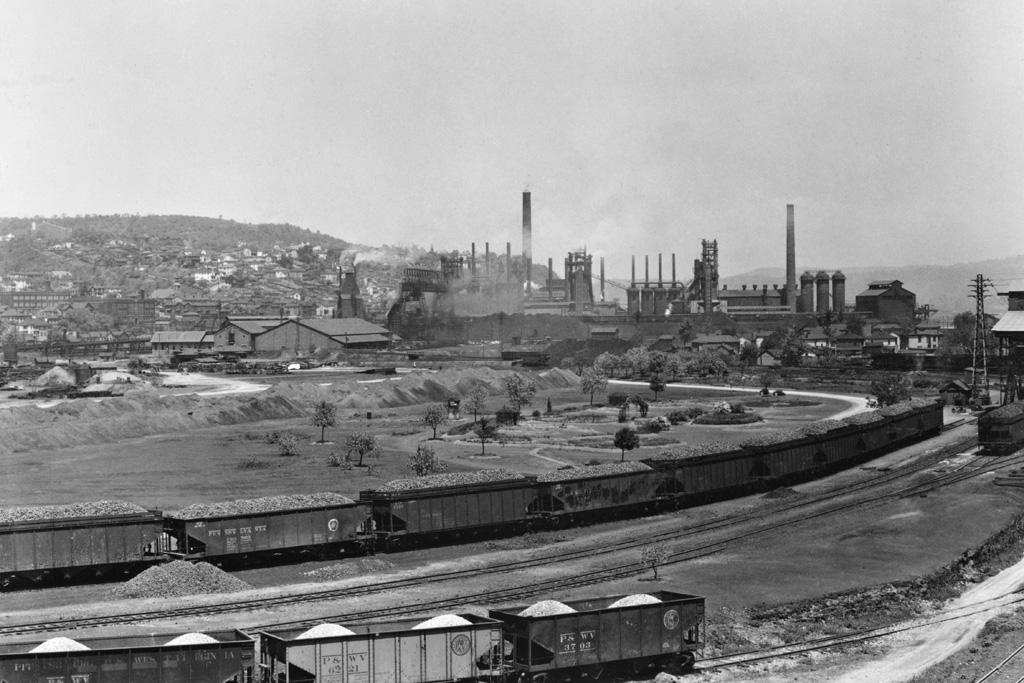

The Depression deeply enmeshed railroads since many of the nation’s primary financial institutions held substantial quantities of railroad bonds. By 1933, the nation’s railroads had seen their revenues plummet to half their 1929 levels. Railroads could not service their own debt, let alone pay for maintenance; capital improvements were out of the question.

President Herbert Hoover had launched the Reconstruction Finance Corporation in 1932 to provide federal aid to state and local governments and to make loans to banks and key industries, including railroads. Roosevelt, Hoover’s successor, increased funding to the RFC while streamlining much of the bureaucracy that had bogged it down under Hoover. For chairman of the RFC, Roosevelt appointed Texas entrepreneur and banker Jesse H. Jones. Jones in turn selected Barriger III to head the railroad division. From 1934 through 1941, Barriger oversaw all RFC lending to the nation’s railroads.

“The bankruptcies and the troubles of the railroads in the ’30s were financial problems,” Jack Barriger said. “Most of them were operating successes….If they made enough money that they could pay their operating expenses, Dad would lend them money to do capital programs. If they weren’t making their operating expenses, I don’t think he was nearly so generous. But, as a result, most of them paid the money back.”

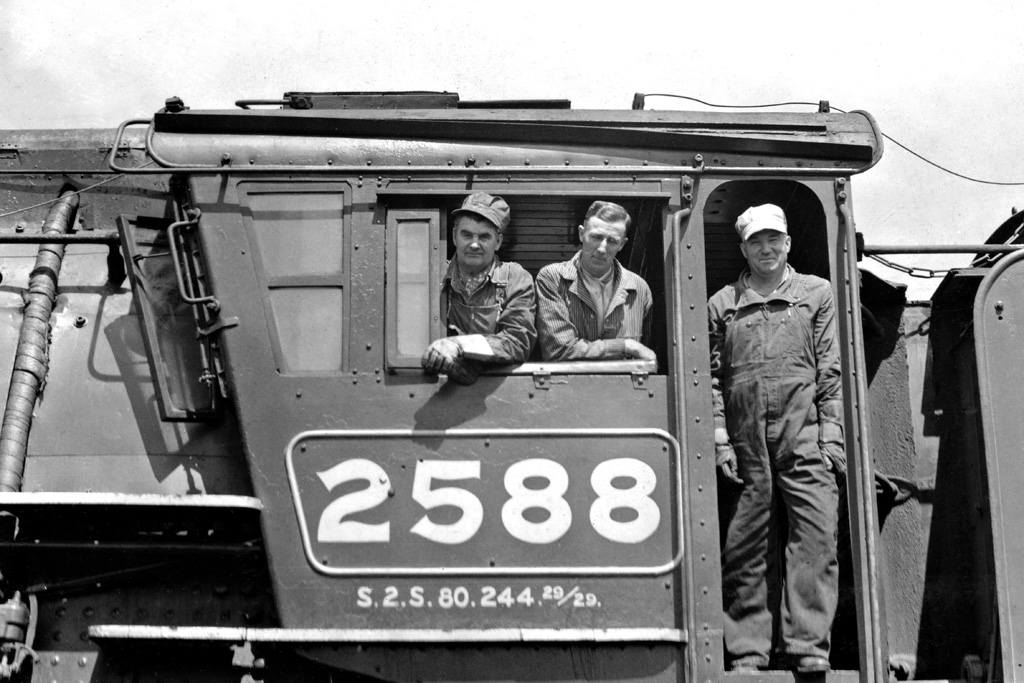

Barriger III’s job was to analyze the railroads that applied for loans and determine whether the RFC could justify making the loans. He took his analysis well beyond simply reviewing the railroads’ financial statements. Motivated by his deep interest in the industry, he set out to examine and document the lines’ physical condition. “In order to make a record of the physical plant — he sort of undertook this himself — he photographed everything he possibly could,” Jack explained. “He began intensively in 1934 and continued through his RFC days in photographing every trip he made.”

“I think as opposed to the modern railfan photographer, who is most interested in equipment, and not very much interested in track, Dad was the other way around,” Jack said. “He focused on track and physical facilities — bridges, interlocking plants, line changes, all the minutia of detail and physical conditions of the railroads.”

Jack explained that nearly anytime his father rode a train “he’d go back to the observation car and just camp, and usually have lunch brought to him.” Barriger prepared meticulously for the trips, arming himself with timetables, grade profiles, track charts, and of course his cameras and plenty of film packs. In his December 1943 “Super-Railroads” article in Trains, he wrote, “It has been my great privilege to have been afforded the opportunity to see most of the primary and principal secondary-route mileage of the railways of this country.”

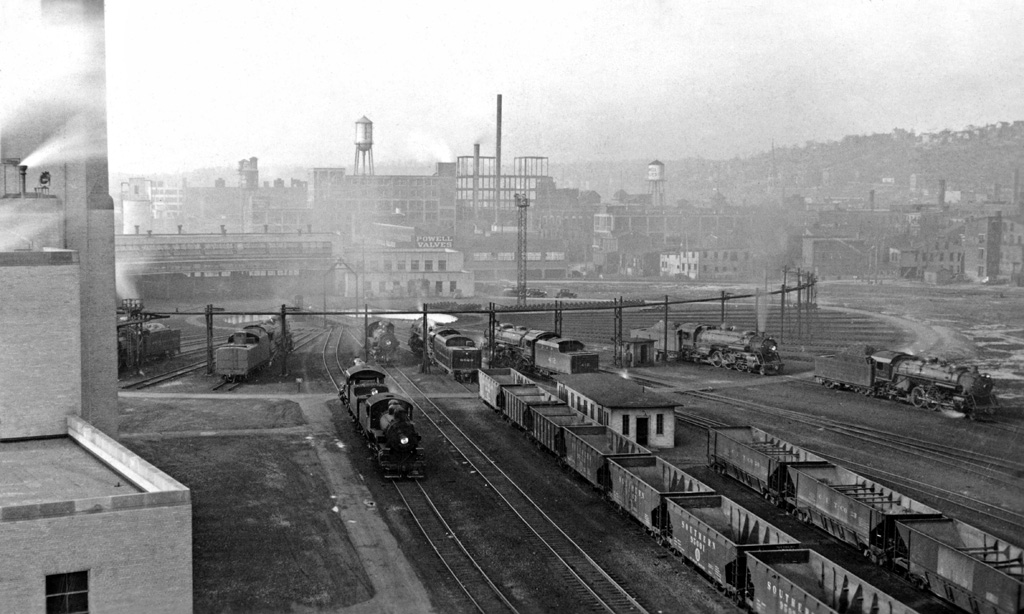

Perched on the rear, open platform of observation cars, Barriger viewed and photographed nearly all of the nation’s railroads during his time at the RFC in the 1930s. His focus and his vantage encouraged views looking straight down the receding tracks, while his fixed-lens folding cameras limited him to a single focal length. Barriger never considered himself a creative photographer; he viewed his work solely as documentation. Yet he clearly had a good eye, and his views encompass much more than track. Seen as a whole, Barriger’s photographs form a time capsule of lineside America during the Depression years.

Typically, Barriger’s only compositional decision involved when to release the shutter, and his timing often was impeccable. He sought out the most significant aspects of railroads’ physical plants, and these features filled the frame with both technical and cultural details that firmly fix Barriger’s photographs in both time and space. Crowds of people line depot platforms and cross the tracks just after Barriger’s train has passed. Automobiles wait behind manually controlled crossing gates. Signaling systems guard complex webs of track at busy junctions and crossings.

Occasionally, Barriger turned around and aimed his camera at the front of his train, looking down long strings of heavyweight coaches at big steam locomotives crossing high bridges or passing dramatic scenery. And sometimes he even disembarked and photographed from ground level during station stops, capturing the depot activities of both trains and people.

Photographic Legacy

In addition to its breadth and variety, Barriger’s photography is also well organized for a collection of its size, which adds immeasurably to its value today. Large albums, arranged by railroad, house pages upon pages of contact prints made from his original medium-format, nitrate negatives. Many of the pages contain detailed notes and diagrams that include caption information and describe complex track arrangements.

Two young women who worked as secretaries at the RFC and prepared exhibits, remembered only as “Skippy” and “Swanny,” cared for Barriger’s photographs. As Jack explained, “They did particularly well at mounting and lettering photographs and this became a large part of their jobs. They lived in Washington all during the ’30s, and they set up these albums and did the lettering with white ink. They were employees of the RFC, but they did this basically with Dad’s stuff. Later both married and moved back to Iowa. Dad would arrange for them to come to the Monon, the P&LE, and after 1965 to come to his home in St. Louis for a week or two to keep the albums up to date.

“Before the RFC, any photographs Dad had just got thrown in the drawer and probably never looked at again,” Jack continued. “But beginning in the RFC days, he was careful to identify them and give the information to Swanny and Skippy, and they would mount and catalog them.” Barriger’s photography remains highly accessible today thanks largely to the efforts of these two women.

On June 23, 2012, the National Railroad Hall of Fame in Galesburg, Ill., will induct Barriger III into its pantheon of leaders in honor of his myriad contributions to the industry. In conjunction with that recognition, the Center for Railroad Photography & Art, the Hall, and the John Walker Barriger III National Railroad Library in St. Louis, Mo., will present an exhibition of Barriger’s photography at the Ford Center for the Fine Arts at Knox College in Galesburg, Ill. The exhibition is free and will be open to the public June 22-24 — Friday from 3 to 5 p.m., Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Preparation for the exhibition has included culling hundreds of exhibit-worthy images from Barriger’s trove; 34 will be shown in honor of Barriger’s avocation as a photographer. Researchers who would like to access Barriger III’s scrapbooks should contact the St. Louis Mercantile Library.

SCOTT LOTHES, a frequent contributor to Trains Magazine, is executive director of the Center for Railroad Photography & Art in Madison, Wis. This story is excerpted from a longer feature of the same title, which appears in issue No. 29 of the Center’s journal, Railroad Heritage. You can join the Center to receive the journal or purchase copies on the Center’s website.