From the smallest narrow-gauge locomotive right up to Big Boy, steam locomotives capture the imagination and occupy a significant place in world history. The steam locomotive’s story runs far, wide, and deep. It continues to unfold today through preservation and restoration. Around every curve, there is another facet of the story waiting to be discovered. Consider then these five mind-blowing facts regarding steam locomotives:

No. 1: A life-changing revolution

It can be argued that the invention of the steam locomotive is as revolutionary as the development of the internet. Travel before the steam locomotive was on foot, assisted by an animal, or on water relying on the wind or the current. All of these methods had pitfalls such as exhaustion, lack of will to perform, or resistance on the part of Mother Nature. The steam locomotive, however, broke down these barriers. Given track to run upon, proper maintenance, and fuel, the steam locomotive moved over greater distance at a higher, consistent speed. It was a revolution like nothing the world had experienced previously.

Consider the coming of the internet in the same light. Like the steam locomotive, the internet has dramatically improved communication, in fact, making it almost instantaneous. We walk around today with personal phones connected via the internet. These phones, really individual computers, have more processing power than NASA’s Apollo rockets — over 100,000 times more power.

The steam locomotive and the internet are both revolutions in their own time.

No. 2: Tires and lug nuts

Steam locomotives have tires. This is not the most mind-blowing revelation when it comes to steam locomotives, but we are all now on the same page. A metal tire is mounted to a driving wheel by heating the tire until it expands beyond the size of the wheel. Once hammered in place and aligned properly, the tire is allowed to cool, shrinking into place and gripping the wheel.

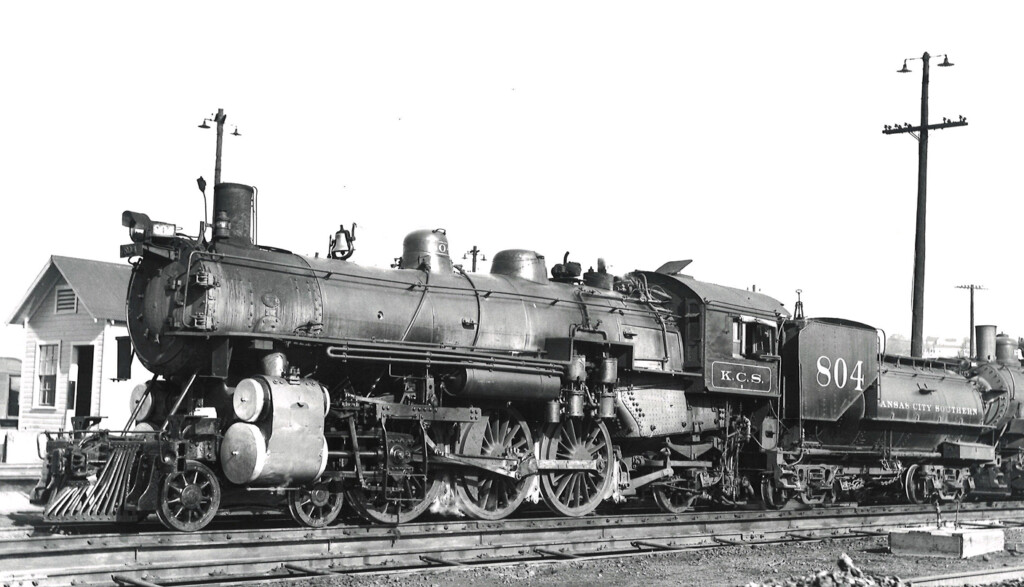

Generally, this was the end of the tire change. There were cases, however, in which tires fell out of alignment. At minimum, tire wear would become excessive. At maximum, the misalignment could cause a derailment. Any derailment is a bad thing, however, if the locomotive involved was pulling a passenger train, the consequences could be catastrophic. As a safety measure to prevent tire misalignment, some railroads, like the Kansas City Southern, placed retaining clips on locomotive driving wheels. The clips were small plates spanning the edge of the driver and its tire. They were held in place with a bolt running through the wheel, giving them the appearance of a lug nut.

And you thought stylish wheels were reserved for hot street rods.

No. 3: Basic black with a touch of graphite

With a few exceptions — Southern Railway green and the Southern Pacific Daylight, to name two — steam locomotives dressed in basic black with a touch of graphite gray about the smokebox. Such bland paint use was not always the case. From the 1820s to 1880s, numerous locomotives and passenger cars displayed dazzling liveries that in some cases boarded on use of color of color’s sake. Example: when the Central Pacific’s Jupiter and the Union Pacific’s No. 119 came nose to nose at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869, to complete the Transcontinental Railroad, color schemes of blue, red, crimson, black, gold, silver, and brass were on display. The display at Promontory was typical in an era where more was more.

Time would curtail the first wave of flashy paint for a rather dirty reason: steam locomotives are filthy machines. Oil, grease, coal dust, black smoke, and cinders combined during a trip to wipe the luster off the most brilliant paint scheme. Additionally, not only was it costly to clean a locomotive, but the more color, the more the equipment cost in the first place. It was time for basic black.

The transition to the standard, drab black steam locomotive of the late 1800s and early 1900s was not made without a touch of myth and controversy.

According to legend, robber baron Cornelius Vanderbilt, owner of the New York Central Railroad, was accused of frivolously expending company funds to adorn his locomotives with gold plated decorations. Angered by such accusations, Vanderbilt ordered that all New York Central locomotives be painted an unadorned black. In reality, the move made economic sense. The extra decoration was costly both to purchase and maintain. Bottom line: a dirty black locomotive displays its true color far better than a dirty gold locomotive.

Most steam locomotives sported a gray or graphite color about the smokebox at the front of the boiler. With few exceptions, this area of the locomotive was not covered with lagging or boiler jacket. A smokebox becomes hot enough to blister standard paint. During the steam era, this posed a problem as heat resistant paints were decades away.

The smokebox graphite color was just that — a mixture of powdered graphite and linseed oil. Once applied and exposed to the heat of operation, this coating would bake onto the surface of the smokebox, protecting it in a manner similar to paint. There were, of course, variations to the basic formula and on some railroads, there was no formula at all; the ingredients were eyeballed for every batch. Being that the graphite coating was mixed in large quantities, the mixing vessels ranged from large tubs to 55-gallon drums. For stirring, shovels and canoe paddles came in handy.

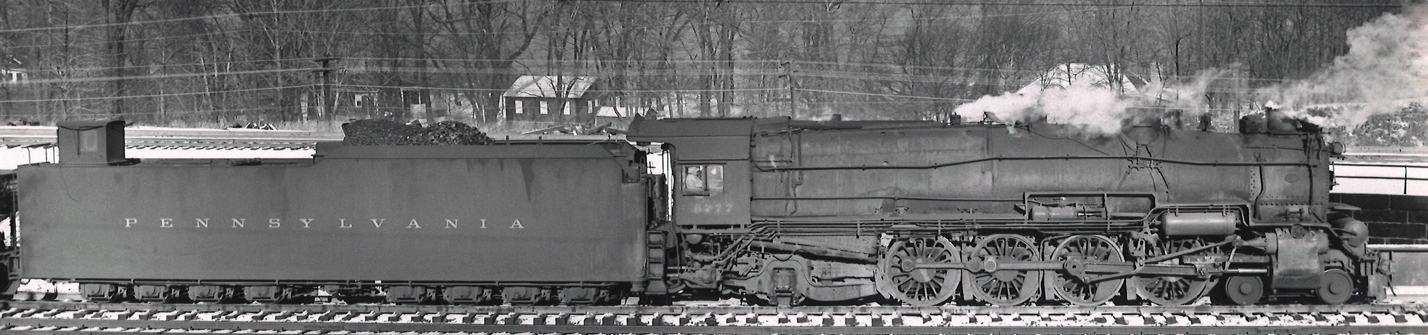

No. 4: In the dog house

In the steam era, prior to the mid-1930s, locomotive cabs were small with room for two people. Such cabs were not the comparatively expansive rooms found on the later-model Union Pacific 4-8-8-4 Big Boys or Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range 2-8-8-4 Yellowstones. Freight trains normally operated with a five-man crew — engineer, fireman, conductor, head-end brakeman, and rear brakeman. Of these five, all but head-end brakeman had a seat provided for them. The engineer and fireman were seated in the locomotive cab, while the conductor and rear brakeman had space in the caboose. The head-end brakeman, however, was in the way without a seat.

The solution to this seating problem came in the form of a shack labeled the “dog house.” It was perched on the rear tender deck, enclosed with a seat, and, generally, heated. The arrangement gave the head-end brakeman easier access to the ground for switching and flagging tasks. It kept him out from under foot in the cab, especially if the fireman had to shovel coal. The dog house, although remote, was relatively safe, as opposed to merely standing in the cab, and the location gave the brakeman a better view of the train.

The Pennsylvania Railroad, Norfolk & Western, Southern, Southern Pacific, DM&IR, and even the Denver & Rio Grande narrow gauge employed dog houses. Several smaller logging roads had them as well. Most dog houses were of a minimalist style. One railroad, however, was inventive when it came to the installation. The Shevlin-Hixon Lumber Co. of Bend, Ore., mounted 1932 Chevy automobile bodies on the tenders of its Baldwin-built 2-8-2 Mikado locomotives. Seats, widows, and doors were left intact. Steam was piped in for heat. Now that’s a dog house!

No. 5: Big plans for the Big Boys

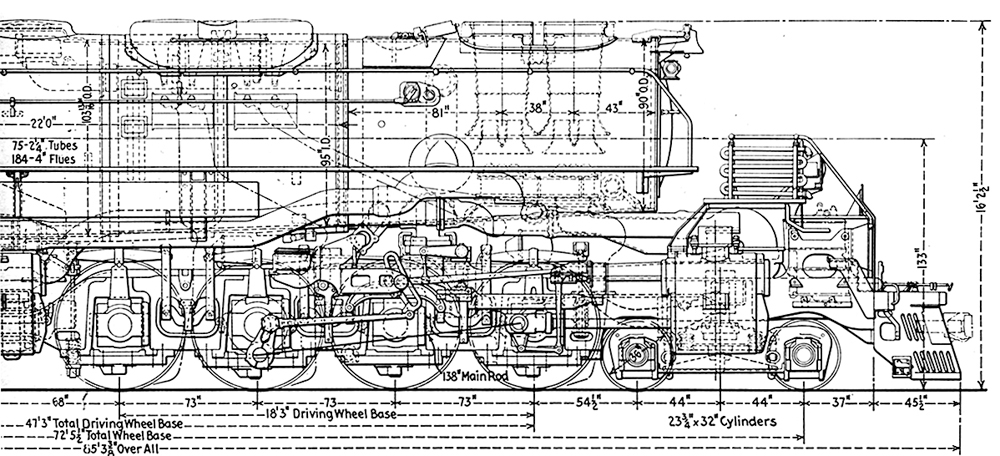

At 132-feet, 9 7/8-inches long, 16-feet 2 1/2-inches tall, and weighing in at 1.18 million pounds in full working order, the Union Pacific 4000-class locomotives were Big Boys. That is the actual locomotive. If the prototype is that big, imagine what the plan drawings looked like.

A full set of plans to build a Big Boy consist of just over 2,000 individual drawings. That’s right, over 2,000 individual drawings. The renderings include specifications for everything from the numbers on the side of the cab, to the electrical wiring, and arrangement of the stay bolts that hold the firebox in place. The most exciting drawings in the lot, however, are the massive erecting views for both locomotive and tender. The locomotive erecting drawing alone measures 30 inches by 12 feet 9 inches.

Think about how well the Big Boys functioned — nearly perfect. They were built on the plans discussed here. Plans that, at the time, were drawn by hand with pen and ink on a drafting table, with no computer assistance. Mathematical calculations were figured on a note pad or slide rule.

The drawings for most steam locomotives took on this scale. And, while they were used to construct working machines, today, they are works of art, in and of themselves.

Camden and Amboy John Bull (1832) by the 1850’s had a tender with a doghouse. It seems to have been a C&A standard.

B&O and RDG had extensions on the fireman’s side of the cab so the head brakeman sat behind the fireman, but only on freight engines. Passenger brakemen rode the cars. RDG T-1’s were built as freight engines so they have the tandem seats.

Dog houses came about due to a ICC ruling that the head brakeman MUST have a seat ” safe from the weather”. Since it was less expensive to build and mount a doghouse on the tender rather than altering the cab dog houses came to be.