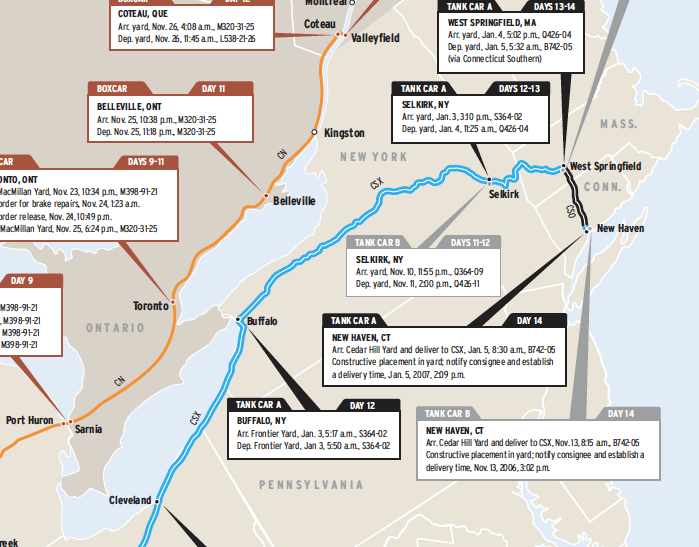

This map shows how four freight cars, threading their way through the North American railroad network, can take about two weeks to cross half the continent. The shippers using these four cars enjoyed tremendous efficiencies by sharing the costs of train crews and locomotives, track and signaling, classification yards, and overhead expenses with the other 1.5 million freight cars in the North American fleet. That’s why railroads can deliver products at a much lower cost than trucks. It’s also why motor carriers continue to have the speed advantage over carload freight.

The journeys made by these cars include events common to most merchandise freight shipments (such as yard classifications, and stops made to add or drop cars) as well as unusual occurrences (namely, bad order car repairs made en route, and travel over the Christmas and New Year’s holidays). The sampling, however, is anything but scientific. We can’t draw any specific conclusions about how railroads move cars based on these trips.

Similarities among the four journeys do appear. (The trips were measured from “Day 1,” the day the car was pulled from the customer.) The cars typically moved about 300 miles or less in a day, although Tank Car A covered distances of around 600 and 700 miles in two separate 24-hour periods. On three consecutive days, Canadian National and Union Pacific moved a boxcar 350-400 miles per day.

The coordination of run-through traffic was swift at Salem, Ill., where UP handed trains over to CSX and CN; no train sat for more than 22 minutes. Travel through major yards or gateway cities typically took one to two days (not counting time for repairs).

The four cars were idle between 56 percent and 72 percent of their total transit time. Still, CN got a boxcar through Chicago in less than 5 hours, and CSX classified a tank car at its Avon, Ind., hump yard in just 10 hours.

There are many variables in a network as large and complex as North America’s railroads. Witness the two tank cars with identical origins and destinations, but taking different routes. Their trip plans were likely determined based on factors in place when their journeys began, such as holidays, yard congestion, and track maintenance curfews.

Ultimately, these trips illustrate the challenges railroads face handling carload freight. Unit trains of 100-plus coal cars and up to 280 double-stacked containers are incredibly efficient — covering long distances at speeds of 70 mph or faster. Not so for today’s railroad workhorse, the single freight car. (Source of car trip data: AllTranstek LLC)

Railroads included in this map:

BNSF Railway; Canadian National; Connecticut Southern; CSX Transportation; Norfolk Southern; Union Pacific

This map originally appeared in the July 2007 issue of Trains magazine.

I would agree with Ms. Harding….As a recipient. I would not care how long the RR stores my shipment for free as long as I don't yet need it. If it arrives before I need it, now I have to provide storage. The pressure comes from manufacturers and suppliers who don't get paid until the car arrives at the customer's location. They should finance their undelivered shipments and take full advantage of the system. A truck cant slow down delivery or hold your goods on board because the driver is needed for another job. The railroad doesn't care.

If the shipper and consignee are both on the tracks and you do not have a just in time delivery then by all means go the cheapest way possible but on the other hand if the consignee is not on the tracks you have an additional cost of delivery and with out REA there becomes a huge logistics problem. Truck is by far the best way as it will get there on time most of the time Rail is for the non sensitive freight in my opinion. I am a retired Owner Operator with 30+ years in the seat.

For some types of merchandise (e.g., non-perishable, not damaged by environmental issues) you may not want the fastest possible service. You want the lowest possible cost of service. If you do a more-or-less constant volume of product you need it to arrive as a steady stream. Intrinsically it does not matter how long the product is in the pipeline, as long as you get it when you need it. There is the cost of the product in the pipeline – so you find the minimum of the combination of cost of shipping and cost of product in the pipeline. If it's a one-off shipment and I need it tomorrow I'll use a truck. If it's a steady stream and it can stay on the rails a while I'll ship by rail.

Sure speed of shipment is important. But it is not the most important factor here. Stability of supply could easily be the most important factor, and if so I might not care that the railroad takes two weeks instead of one to get it to me, as long as it is consistent and the cost of the extra week is cheaper than the differential cost of the extra product left in the hands of the shipper.

Remember, what goes in eventually comes out, so the cost of what is in the pipeline is not the direct cost of the product but the cost (e.g., interest, other associated factors) of having that money tied up thusly rather than free to be used for other purposes.

Heads would have rolled for this kind of performance on the NYC …. 40 years ago! Have we really gotten worse?

6 days in Danville – perhaps the consignee was not ready to receive the load since it was so late.

I hate to say it but if I were a business that relied on rail for my product I most likely would be out of business, in this day and age most manufacturers use Just In Time and if you are not there with the product the whole place will shut down. I will stick with truck freight much faster. Hope I said this right.

Pathetic. Hopefully the typical percentage of bad orders is magnitudes lower than in this sample. Still, it should not take this long to process them. Cars sitting in multiple yards for days at a time should be a thing of the past. What is going on in Danville, VA? Almost 6 days there and then 2.5 hours to go to the east side of town!

Ugly numbers