Intermodal haulage on railroads initially resembled loose-car railroading: Cities of varying sizes had ramps that originated a few flatcars, which were added to merchandise freights. A trucker, though, could beat that service easily. Larger cities generated solid intermodal trains, but the cost of terminals, equipment, and operations made the business lucrative only in lanes of 500 miles or more — a narrow and competitive market segment.

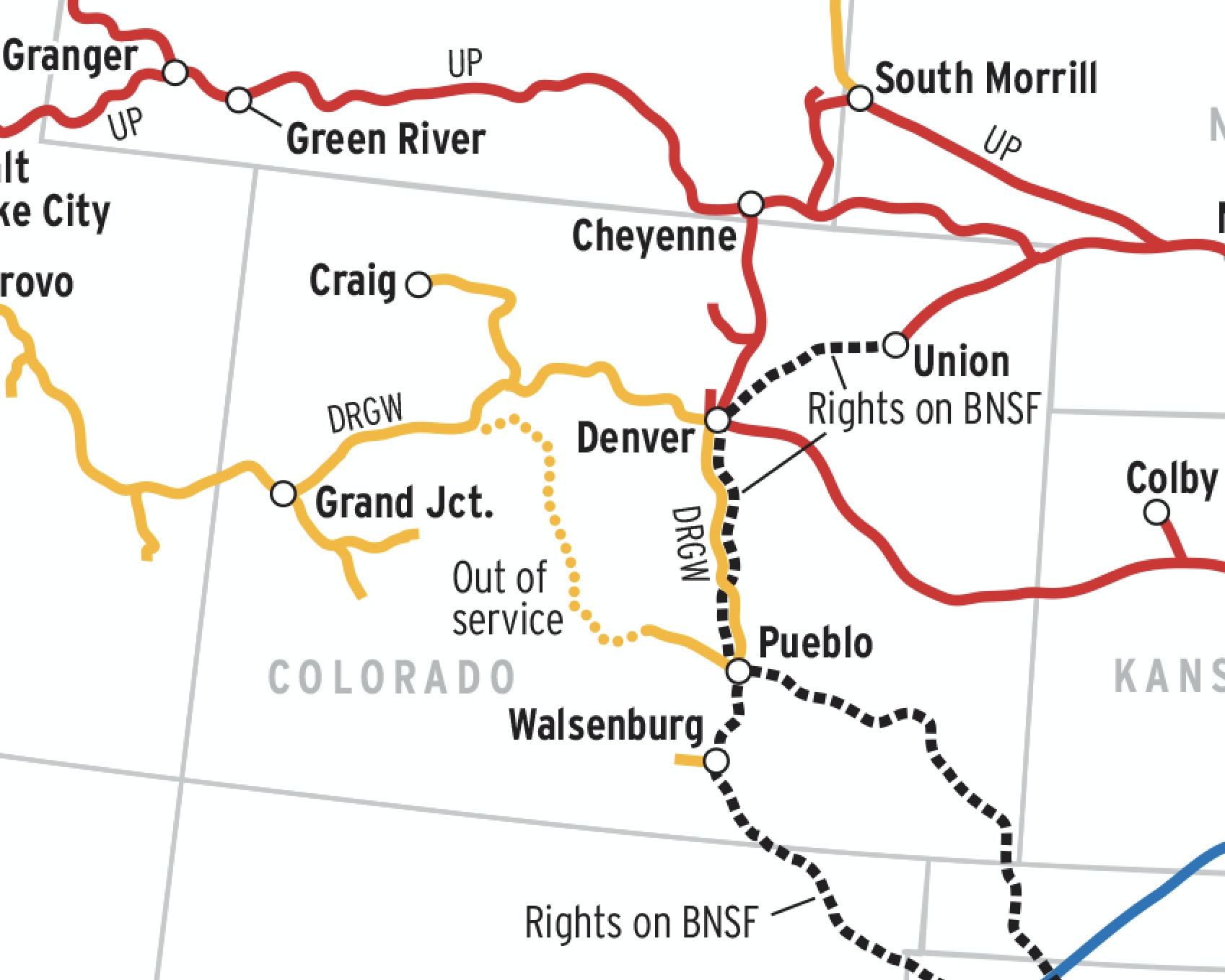

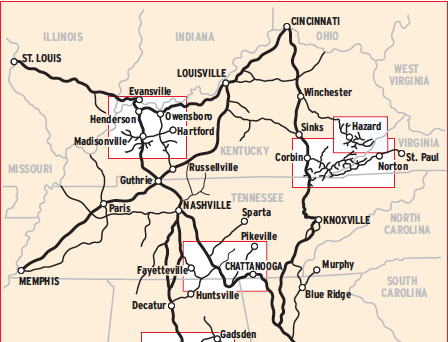

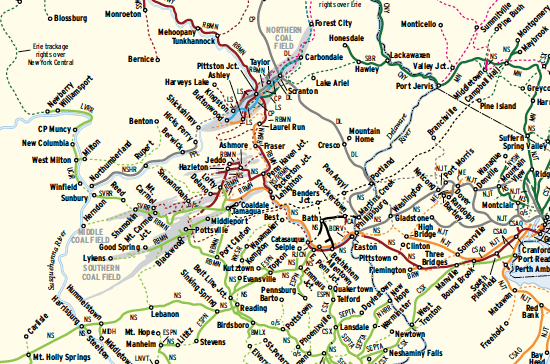

Deregulation came to intermodal traffic in 1981, and by first-quarter 1984 — when I surveyed Class I railroads to compile this map of dedicated intermodal trains — some gradual changes could be seen:

Fewer terminals: To maximize revenues, railroads abandoned loose-car intermodal in favor of dedicated trains linking a handful of high-volume terminals. In 1973, the Class Is showed over 1,000 intermodal ramp locations in the Official Guide; by 1983, the number had dropped to 500 or so (today it’s about 200). In longer lanes, trains set out and picked up cars at intermediate points, which (as of 1984) are labeled on this map.

Mixed trains: Burlington Northern, Conrail, Southern Pacific, and Union Pacific added auto racks or auto-parts cars to some dedicated intermodal trains. Other roads, including SP, Conrail, and Norfolk Southern, still ran mixed intermodal-carload freights, which are not on this map.

Short-haul’s last gasp: In the late 1970s and early ’80s, some experimental trailer trains were launched in lanes of 400 miles or less. Many succumbed to low margins, high costs, and lukewarm demand, including Illinois Central Gulf’s Chicago-St. Louis trains (dropped in 1985) and Grand Trunk Western’s Chicago-Detroit service (gone by 1986). Florida East Coast’s 350-mile speedway thrived, thanks in part to its participation in connections’ longer lanes, but cost was still a factor.

Varied frequencies: Since not all trains ran every day, numbers on the map show the heaviest days of operation. On SP, UP, C&NW, and Conrail, the numbers were averaged to account for weekday-only piggyback trains and once-a-week stack trains.

Double-stack’s infancy: The shift to double-stacks had just begun, with traffic for American President Lines and Sea-Land moving in once- or twice-weekly trains between West Coast ports, Chicago, and New Jersey. Clearance projects and truck-rail partnerships would later cement the stack train’s efficiency.

Railroads included in this map:

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe; Baltimore & Ohio; Burlington Northern; Chicago & North Western; Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific; Conrail; Denver & Rio Grande Western; Florida East Coast; Guilford Transportation; Grand Trunk Western; Illinois Central Gulf; Norfolk Southern; Seaboard System; Southern Pacific; Union Pacific