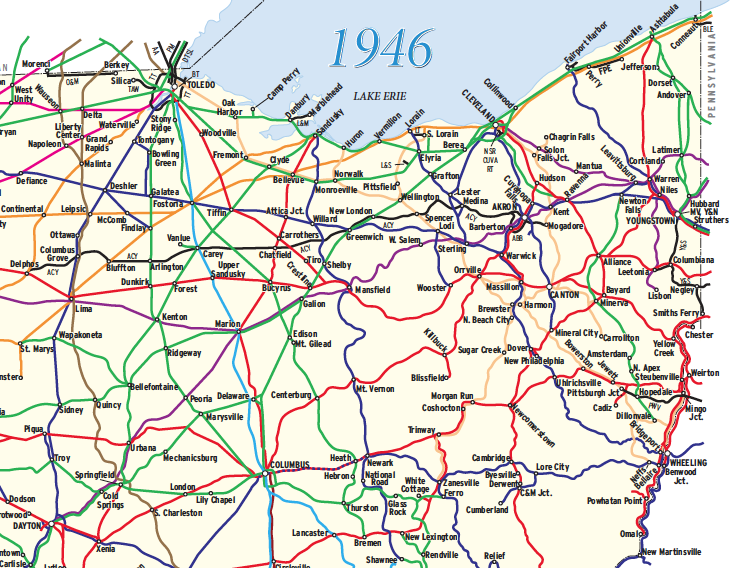

This is a snapshot of traffic across the Continental Divide in 1980 and 2000 on U.S. transcontinental routes. It’s inherent in map-making that accuracy gets sacrificed on the altar of clarity: traffic density is by no means uniform across the shaded line segments, and a slightly different picture would emerge were the snapshots taken in the years preceding or following.

Traffic has increased unequally, proving that as railroading enters its third century North America, topographic features, political boundaries, and strategic position cannot be written off as historical conditions. But these conditions do not always affect routes in impartial measure.

Consider the Sunset Route. It has the lowest and easiest rail crossing of the divide in the U.S., occurring at an unnamed point about three miles west of Wilna, N. Mex. Traffic growth on the Sunset, mostly containers moving from and to the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, Calif., has been less than half the growth enjoyed by its close competitor, the former Santa Fe — a route which has so completely dominated transcontinental traffic it’s become “the transcon.” The difference is strategic position: the Santa Fe shoots straight to Chicago while the Sunset does not, making irrelevant the higher elevation of Santa Fe’s crossing at Campbell Pass (also Campbell’s; either way, a name fallen into disuse).

Elevation and difficulty of approach matter greatly for the two Colorado crossings. It makes them disproportionately expensive to operate. Paradoxically the Rio Grande, with the two worst crossings of the divide, was helpless to consolidate its traffic to one line because of its strategic need to maintain connections at both Denver and Pueblo, and deliver coal to Denver. UP, acquiring these routes with its 1996 merger with SP, in effect moved the connection points from Denver and Pueblo all the way east to Chicago and Kansas City, and, by consolidating coal traffic to the Moffat Tunnel Route, accomplished what flummoxed the D&RGW for a half-century.

Union Pacific’s Overland Route, transcontinental tonnage champion throughout the 20th century, by now may be surpassed by the Santa Fe. The Overland already has fewer trains, but has a higher proportion of heavy commodities, notably grain and soda ash. Capacity constraints that dog the Sunset Route aren’t a big issue on the Overland, which is all multiple-main-track.

Nor is capacity lacking in Montana despite the loss of two of four mainline crossings of the divide since 1980. Neither the GN or NP routes, lacking a huge population center at their western end and constrained in their natural territory by the Canadian border, has the same prospects for traffic growth as do the southern routes.

Engineering only gets you so far (as the Milwaukee Road discovered to its chagrin) — ultimately the railroad has to take you where you want to go. For the forseeable future, that’s Southern California.

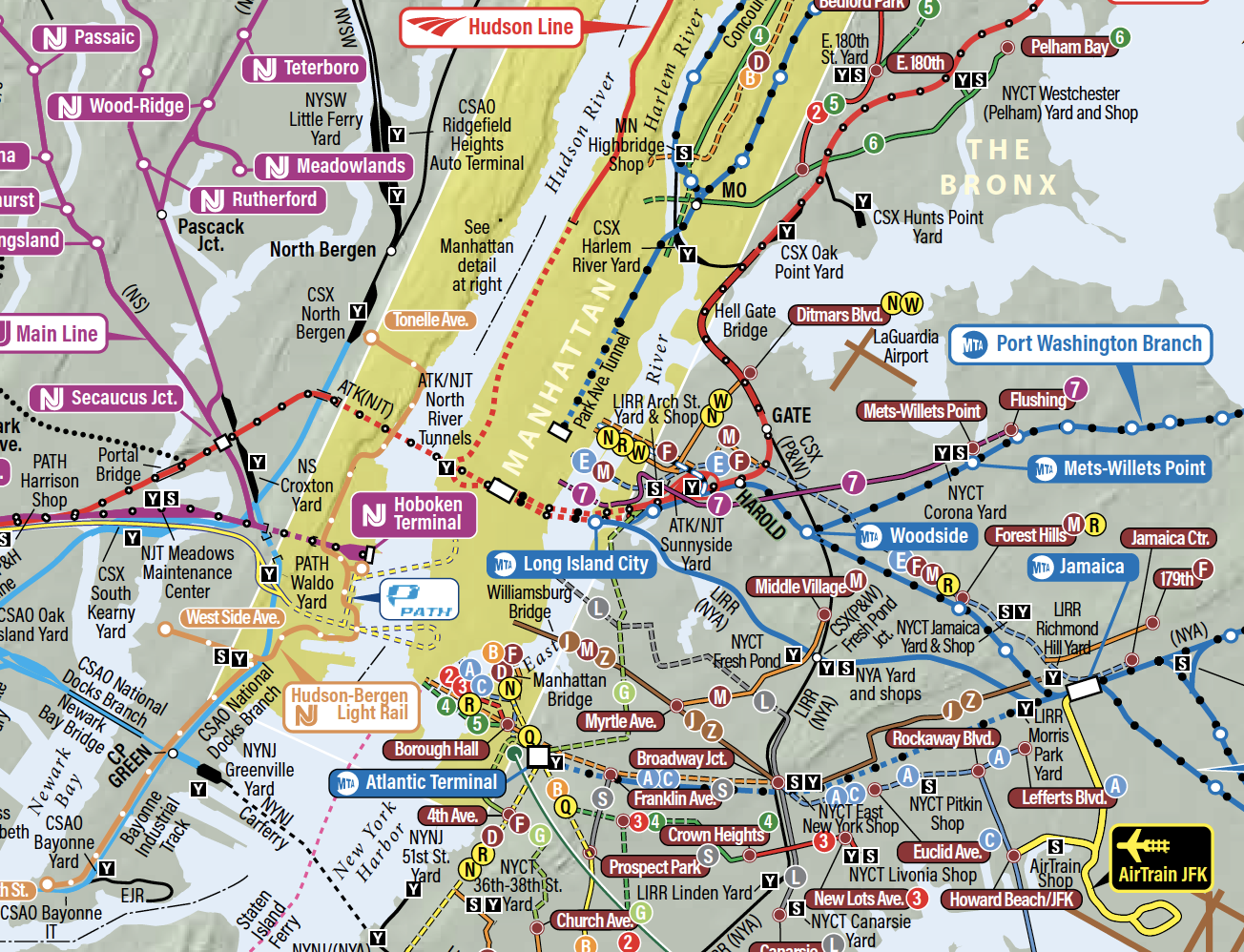

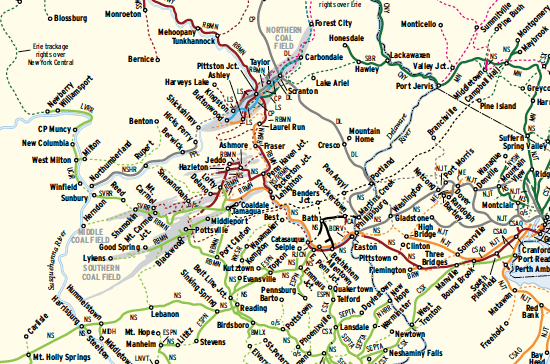

Railroads included in this map:

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe; BNSF Railway; Burlington Northern; Denver, Rio Grande & Western; Montana Rail Link; Southern Pacific; Union Pacific

In the case of the Milwaukee, it's true that "engineering only gets you so far." You also have to keep up with the Joneses. The Milwaukee logically was the best engineered at the time it was built since it was the last built and engineering techniques improve with time, but it did little to improve that plant after its initial construction. And engineering couldn't overcome its horrible profile. Being "well-engineered" is just another of the "Myths of the Milwaukee."

http://www.trainweb.org/milwaukeemyths/