Look closely anywhere a road or pedestrian walkway crosses railroad tracks in the U.S. and you’ll see a small rectangular blue and white sign attached to the nearest warning device. Officially dubbed an Emergency Notification System, or ENS, sign, it has two vital pieces of information: a U.S. Department of Transportation “National Inventory Number” unique to that crossing, and a phone number that goes directly to the dispatching desk of the railroad responsible for movements at that location.

Lack of widespread knowledge about the existence of these signs has, unfortunately, led to needless tragic accidents resulting in loss of life, derailed trains, and millions of dollars in property damage. For example, at about 10 p.m. on Nov.16, 2023, a 9-1-1 operator in Southwest Michigan, receiving a call about a disabled vehicle stuck on tracks, called an emergency number for what the operator believed to be the railroad associated with the crossing. The CSX dispatcher fielding the call would have stopped all trains on that portion of the Chicago-Grand Rapids route while attempting to identify the exact location.

The actual crossing, however, was at Lakeside Road on Amtrak-owned tracks hosting 110-mph passenger trains. Dispatchers monitoring train movements at a Chicago Union Station console were unaware of the stalled vehicle before westbound Wolverine No. 355 slammed into a tow truck that was trying to move it. The crash derailed the locomotive and first coach, ripped up track, and injured the engineer plus at least 10 of more than 220 passengers and crew on board [see “Dispatching center error played part in Amtrak collision …,” Trains News Wire, Nov. 20, 2023].

In the aftermath, all eight departures on the Chicago-Michigan corridor were canceled for the next 24 hours, affecting thousands of passengers. Had the stalled vehicle’s owner or the tow truck driver known to look for the blue sign mounted on both crossing gates, direct communication to Amtrak’s dispatcher could have stopped the train before the crash occurred.

Regulatory requirements

Those blue signs stem from Section 205 of the Railway Safety and Improvement Act of 2008, which mandated a 2012 Federal Railroad Administration rule that led to the adoption of Emergency Notification System requirements. The same legislation that required railroads to install positive train control technology also attempted to provide information on who to call to stop a train. Too many hapless truck drivers had watched helplessly when their lowboy trailer got torn to bits after being inadvertently grounded on a raised crossing. Coincidentally, the requirement arrived during widespread deployment of cell phones and better wireless reception in rural areas.

The regulations involved gave railroads until 2017 to install uniform blue signs at both sides of every grade crossing.

Each sign displays:

- A unique National Inventory Number to be listed in a USDOT database. Many carriers also choose to put the rail milepost and a brief location description on the sign so a railroad dispatcher might quickly verify a crossing while confirming the DOT number with the citizen caller.

- A direct, toll-free phone number capable of immediately reaching someone at the railroad capable of communicating with train crews, controlling signals, notifying maintenance personnel, and connecting with local law enforcement.

Signs must:

- Be 12 inches wide by 9 inches high, or larger. Some of the early, and most more recent, signs are larger, a move applauded by safety experts.

- Have white text at least 1 inch high on a blue background, but the National Inventory Number may be black text set on a white rectangular background.

- Reflect light at night.

Those requirements are included in more than 75 instructions in the “Emergency Notification Systems for Telephonic Reporting of Unsafe Conditions at Highway-Rail and Pathway Grade Crossings” rules. They spell out procedures to be applied in varying circumstances for dispatchers, train crews, and maintenance workers that must be followed when a call is received about any “unsafe condition” at a highway or walkway crossing. These might include a stalled vehicle, obstructed view of a train’s approach, or a warning device either not activating for a passing train, or continuing to operate without a train present.

In addition to first handling immediate operating considerations, the dispatcher must notify police whose jurisdiction includes the crossing, “to direct traffic or carry out other activities to maintain safety at the crossing,” and contact track and signal maintainers capable of correcting malfunctioning or damaged equipment, such as a broken gate or grounded track circuit.

The dispatcher has to be instantly reachable except at crossings on light traffic or intermittently operated routes where train speeds are limited to 20 mph or less. In those cases, the railroad could utilize an answering machine or a third-party answering service, as long as messages are retrieved and acted upon at the start of the next business day. Additionally, if more than one railroad dispatches trains at or maintains the crossing, one company must be designated as the “primary dispatching railroad” and is required to immediately notify the other carriers when an unsafe condition is reported.

When a call comes in

Trains wanted to see exactly what transpires after a blue sign call comes in. While Class I railroads generally handle emergency calls in centralized, high security dispatching centers, visits to Northern Indiana Commuter Transit District’s operating headquarters in Michigan City, Ind., and Metra’s Chicago dispatching facility revealed how potentially dangerous situations are promptly rectified.

“The South Shore has 161 highway crossings,” NICTD Chief Dispatcher Sara Krga notes on a tour of the darkened dispatcher’s enclave. A dedicated “blue sign line” sounds directly at the console. “They know its distinctive ring, and are ready with a list that cross-references DOT numbers with crossing locations,” she adds.

Crews are notified by radio. Based on information from the caller and other circumstances, “the dispatcher will determine if a train must stop and flag the crossing or slow down to restricted speed. Law enforcement and first responder information is keyed to each location; one of three signal maintainer districts will then be contacted,” says Krga.

Calls are relatively infrequent and might involve a misbehaving gate or blocked crossing. But protocols are a part of NICTD’s safety program administered by Chief Safety Officer Kristen Coslet. “We touch base with emergency responders in our various territories three times per year, including staged mock disaster drills, and work with Operation Lifesaver to come up with outreach programs,” she says. These include familiarizing area 9-1-1 dispatchers with how blue-sign communication is railroad-specific in a region with numerous intersecting lines.

For Metra, handling ENS calls gets a bit more complicated, especially on routes where dispatching and maintenance responsibility for crossings is split among host railroads. Southwest Service trains come out of Union Station on Amtrak (one highway crossing), roll on Metra to Forest Hill (one crossing), and then Norfolk Southern to the end of the line at Manhattan, Ill., (38 highway and pedestrian crossings with DOT numbers, plus about a dozen walkways at commuter stations within the immediate vicinity of a protected crossing). The NS dispatcher who gets the call in Atlanta quickly relays it to NS’ Landers Yard office on Chicago’s southwest side, where personnel advise their own maintenance staff and forward the information on to Metra operating crews. Similarly, Union Pacific and BNSF dispatchers handle all communication and summon maintenance regarding crossings on lines hosting commuter trains.

At Metra’s Consolidated Control Facility, separate dispatching desks are maintained for each of the Metra Electric, Milwaukee, and Rock Island districts. Facility director Greg Godfrey explains that blue-sign calls from any of 237 crossings for which Metra is responsible go directly to the correct dispatcher. “Each district has its own specific number to help sort it out quicker in our office, and they ‘ring’ on both phones, for example, in the Rock Island where there are two dispatching desks,” he says. Any resulting restriction imposed by the dispatcher instantly impacts the positive train control system for that route and triggers an incident report.

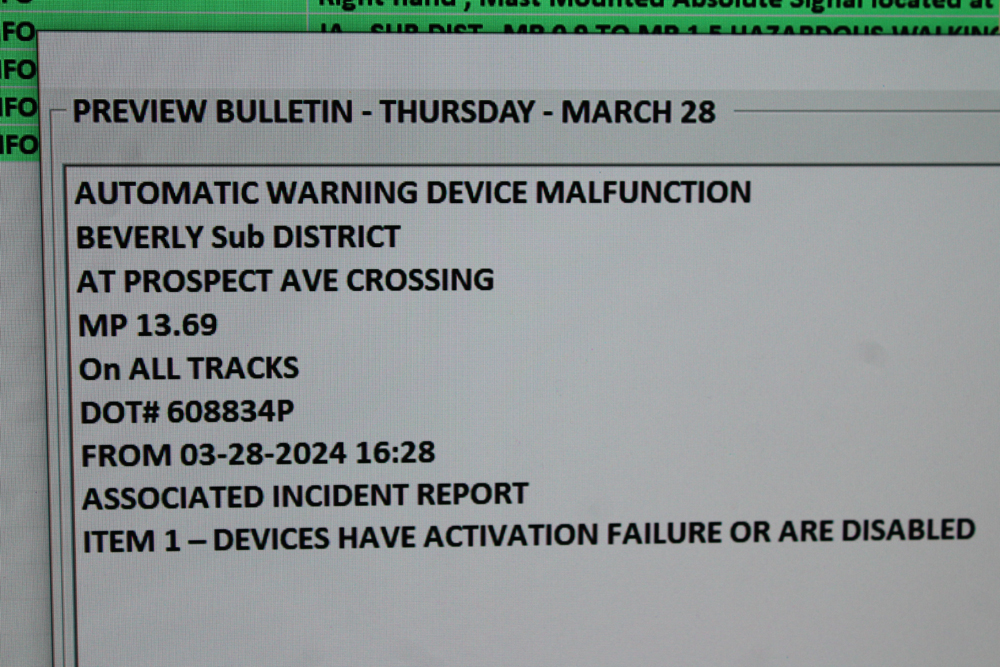

Suppose someone calls the number on the sign after observing gates remaining in the lowered position on the Rock Island District’s Prospect Avenue crossing in Chicago’s Beverly neighborhood, a situation that tempts motorists to assume a train isn’t coming and drive around the gates. At an off-line console, Godfrey demonstrates what happens.

“If the dispatcher is handling another matter, they will put that call on hold to take the blue-sign call. While the caller is on the phone, the dispatcher will load a bulletin that initiates an FRA incident report and ask the person to again verify the DOT number to ensure the crossing is correctly identified,” explains Godfrey. A handy database he manages cross-references every DOT crossing number with street names, city locations, and nearby intersections; there are many “Main Street” entries. A look the Beverly branch train display shows how many highway crossings are crammed into just a few miles of right-of-way, so misidentification is a real possibility without these ancillary references. Once the location is validated, that rail segment gets flagged for an automatic warning device malfunction.

“When I hit ‘activate’ it immediately floats into the PTC world to impede any movement at that crossing,” says Godfrey. “An ITEM 1 restriction requires the train crew to stop and protect, because when the call comes in, we don’t know whether there is a track disturbance potentially caused by a vehicle or problems with circuits. Most of the time we put the restriction on all tracks; we don’t know what is broken so we assume the safest course,” he adds. The center’s chief dispatcher usually jumps in at this point, calling the appropriate maintainer to advise of a possible broken gate. Metra and/or local police are also alerted to deal with auto traffic, while the segment dispatcher who received the call is busy relaying instructions to train crews. “Our philosophy: divide and conquer,” Godfrey notes.

As the episode is investigated, the incident report is modified. An ITEM 1 may revert to a “stop, look, and proceed” ITEM 2 restriction if there are an adequate number of flaggers to stop traffic. The resulting log pinpoints when the incident started, actions taken, and how it was resolved. “A huge database is created from these reports that may suggest deficiencies to be addressed,” Godfrey says. This could be traffic bollard installation at a particular location to keep autos off the tracks, or identifying crossings that are especially prone to blocked freight trains.

In 2023, Metra, CPKC, and NS dispatchers registered 2,212 automatic warning device malfunctions that required an ITEM 1 restriction. Very few were the result of ENS calls from the public, since Metra operating and maintenance personnel have constant eyes on the property and are usually in a better position to observe equipment anomalies. Godfrey says that through mid-2024, blue-sign calls are trending about six per month. But checking September 2023 crossing malfunction data, he found that 11 people called the police first to report a problem versus one person utilizing the number on the sign. “Had they called directly, any issue would have been addressed much faster,” he notes.

The widespread deployment of ENS signs and the calls they prompt have made it easier for railroads, and the FRA, to accurately tabulate instances where crossings are blocked for an extended time by stalled freight trains. Far from just an inconvenience to motorists, anytime a crossing is blocked creates a potential temptation for pedestrians to crawl on or under the stalled train. Not only is this perhaps the most dangerous act a trespasser can make — trains can move at anytime — but an unseen train on an adjacent track may lurk on the other side.

For all of 2023, the FRA reports there were 2,192 U.S. crossing collisions that caused 245 fatalities and injuries to 763 people. It isn’t possible to know what role, if any, the presence of a blue sign played in each incident; the decision to drive around gates or dispense with simple precautionary measures to stop-look-listen and “always expect a train” couldn’t save drivers who failed to take them. But if an additional life could be saved or damage avoided by expanding the public’s knowledge of what to do when an unsafe condition is detected, then progress will be served.

Updated 2023 FRA report stats on July 24, 2024.

[my last comment was inexplicably interrupted in mid sentence]

“FOR HELP WITH AN EMERGENCY AT THIS CROSSING” in large letters, and “CALL THIS NUMBER” below it.

I know, this is all spelled out in the fine print on the sign, and if people would only take time to stop, explore the environment around the crossing, and read the sign completely instead of panicking in an emergency they would figure it out. However, 20+ years in emergency health care has taught me that things need to be very clear, simple, and direct to be effective in emergency situations.

Excellent article! I have noticed the blue signs at crossing for years, but–call me dense if you want–it never occurred to me that I could use the information for an emergency such as a blocked crossing. The sign is blue, which among highways signs means “mundane general information”, not “Emergency!” Being small and inconspicuous, it would not catch the eye of someone in an emergency situation; it gives the impression of being something like a milepost number for company use. A QR code would be useless for me, as I don’t have a cell phone that would know what to do with a QR code. If they are intended as an emergency resource for the general public, they need to be designed in a way that makes that clear, such as being red and headed with “

I called one of these numbers once to report a malfunctioning gate. No one answered, though I stayed on the phone a long time (maybe half an hour.

I’m also an OLAV but I am also a cybersecurity professional, I wanted to say as much as I love the QR code idea, it’s also fraught with weakness as scammers can slap a malformed QR sticker (i.e., one that points to a scam website that can introduce malware onto one’s device or just plain bad information) overtop of the existing one without the user being aware of the change.

Don’t get me wrong, it certainly is doable, you would probably need to have matching text to go with the QR code, i.e., the phone number and ID of that crossing because there are those who won’t even touch a QR code with a 10 foot pole!

I am very active in Operation Lifesaver. I work OL booths and sometimes do presentations. I always emphasize calling the number on the blue signs as it goes into the owning railroad’s dispatching center and get’s quicker emergency action. I also emphasize that the crossing identifying number on every crossing is unique to that crossing like “your house address” is unique to your house.

I really like the QR code idea and wonder it has not been implemented.

2,516 fatalities is more than 10 times the actual fatalities for 2023.

Those signs are virtually useless if a vehicle has stalled on the tracks. They face outward from the crossing and the occupants/driver cannot see the sign.

Blue signs are a nice idea, but very 1950s. As another commenter said, use a QR Code, for goodness sake! A very large QR on a much larger sign, so even those who know nothing about rail will actually SEE it. A big sign that says, “EMERGENCIES SCAN HERE.” Nearly everyone has a smartphone now, and a QR code would contact the right dispatcher in seconds. Signs are useless. 800 numbers are too slow. QR codes work.

Great effort, indeed. I wonder why a QR Code that links the caller with a phone call or text with all the details of the crossing, etc.? Just make life easier when you see the situation as being dire, I say. Thanks!

Thank you for this article! Drivers are ignorant of the blue crossing sign.

Ed Burns

Retired Class 1