Rail yard basics

What are rail yard basics? Think of a yard as a giant sorting machine. It’s a place where freight trains are put together and taken apart. In the railroad industry, freight pays the bills. The faster cars are sorted and back on the road the sooner the cargo is delivered and an empty car is ready for another customer.

When a typical mixed freight train arrives at its destination yard, workers take away the road locomotives for servicing, then the train’s cars can be sorted according to destination. For example, a track in the yard may hold cars bound for Chicago. As trains arrive and are taken apart, all the Chicago-bound cars wind up on that track.

The cars are assembled into trains at regular intervals. If the railroad’s line to Chicago passes through Milwaukee, the cars bound for Milwaukee will be added to the Chicago train, along with cars for other cities along the way.

Finally, with cars coupled together and air brake hoses attached, road locomotives arrive from the engine terminal, a rested crew climbs aboard, and the train is on its way.

A high-priority train needing to reach its destination swiftly is less likely to pick up and drop off cars along the way. A unit train hauling a single commodity, coal or grain perhaps, will shuttle back and forth from loading point to customer with no need for switching.

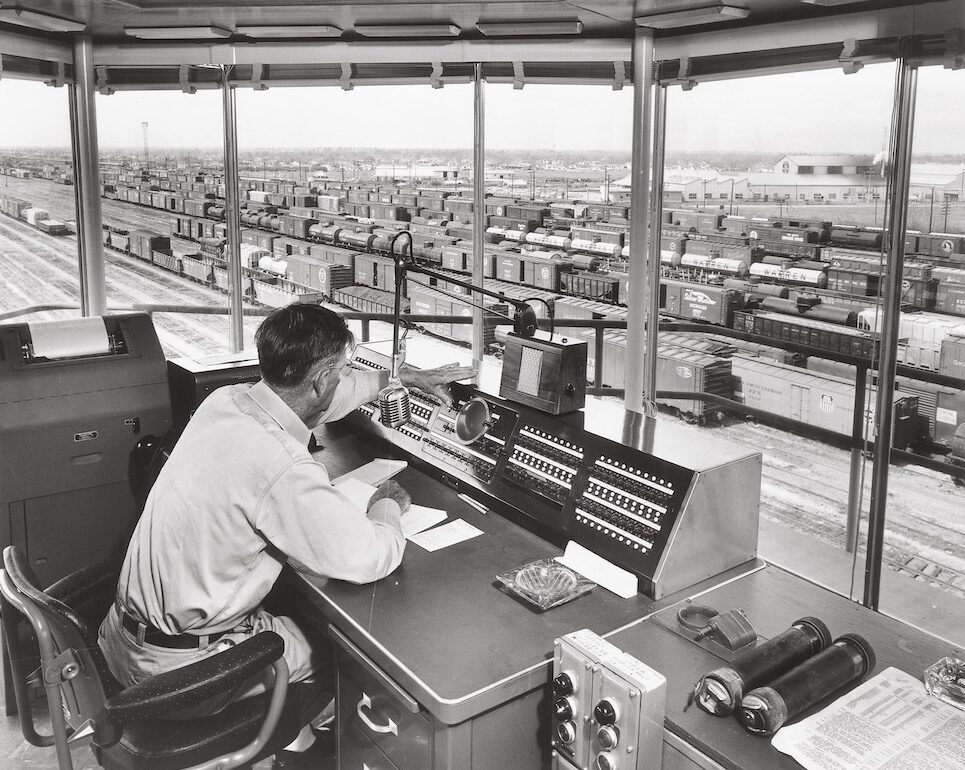

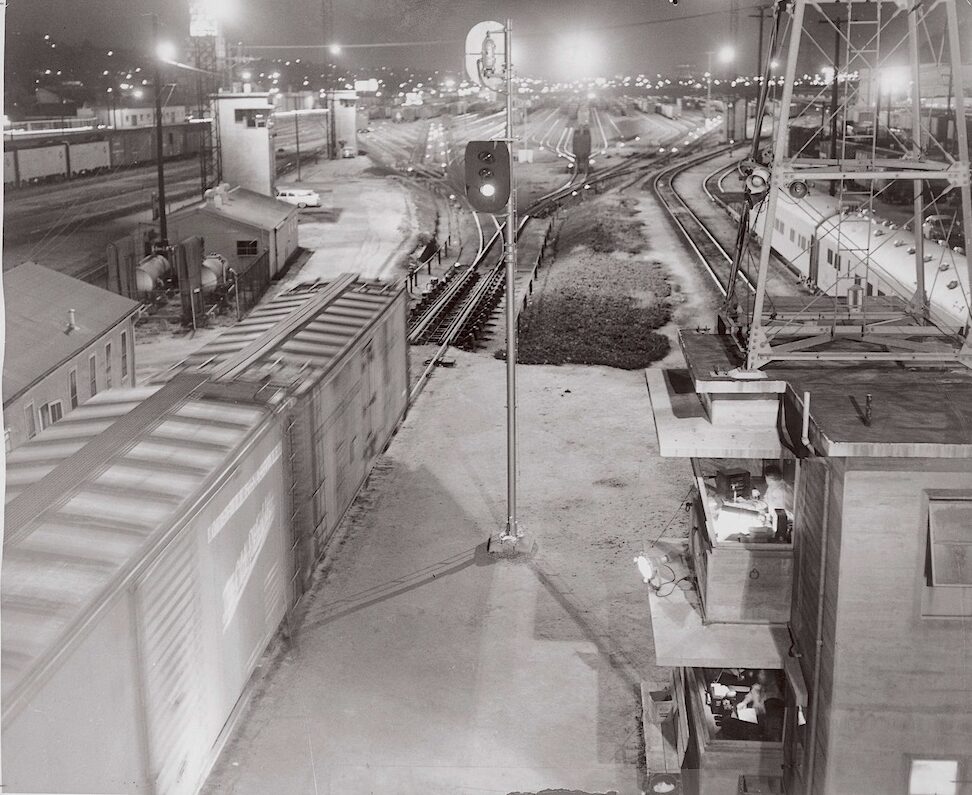

There are two common types of yards: flat and gravity. Flat yards are the most common. Here switch engines move cars from track to track until all are properly sorted. Flat yards are relatively easy to build but the back-and-forth switching movements are time-consuming. Gravity-switched yards — also called “hump yards” — are more expensive to build and maintain, but they can be more efficient. In a gravity yard, a locomotive shoves inbound cars up a man-made hill. The cars are uncoupled at the top of the hill to roll down into the main body of the yard. Remote-controlled switches route the car to its classification track.

If its destination track is nearly full, a freely rolling car will strike the other cars at too great a rate of speed. In the early days, brakemen rode the cars downhill, controlling speed by hand-turning a brake wheel. In time, an automatic braking system took over this dangerous task. Cars are weighed as they crest the hump and as they roll downgrade, a device measures their rate of acceleration as they approach the car retarder system where powerful clamps slow the cars by pressing against the wheels. A light car bound for an empty track needs little or no braking, while a heavy car heading for a crowded track needs considerable braking.

In addition to the classification tracks, yards have tracks for repairing cars damaged in transit and for storing cabooses between runs. In the days of steam, engine servicing areas often included a roundhouse, sand tower, ash pit, and coal and water supplies. Passenger trains have their own designated yard and engine facilities, generally located as close as possible to the terminal so they can be swiftly cleaned, serviced, and resupplied between runs.

From the book Faces of Railroading, Kalmbach Media 2004.