Answer: The initial route of a rail line is a compromise between cost, grade, and curvature. Early railroads were often built as cheaply as possible and improved when traffic and profits justified the cost. That’s when the old alignment can be abandoned in favor of the new, like parts of the Union Pacific’s original Transcontinental route, or kept in service.

Michael E. McGinley, a senior track engineer at Advanced Rail Management Corp., says that given a freight train speed of 70 mph, curves less than 2 degrees (about a 3,000 foot radius) do not slow trains nor increase rail wear compared with straight track. He added that grades often limit a train’s speed more than curves. This leads right back to the cost-benefit analysis.

McGinley says that passenger services change the business case for faster track, since increasing speeds to reduce travel time is more important than cost savings on operations and maintenance. — Tyler Trahan, a Trains contributor

Not stated as clearly as it could be, a curved route is often used to control gradient: Longer = lesser grade between two points of different elevation. You can’t straighten the route on many western lines without greatly increasing the gradient.

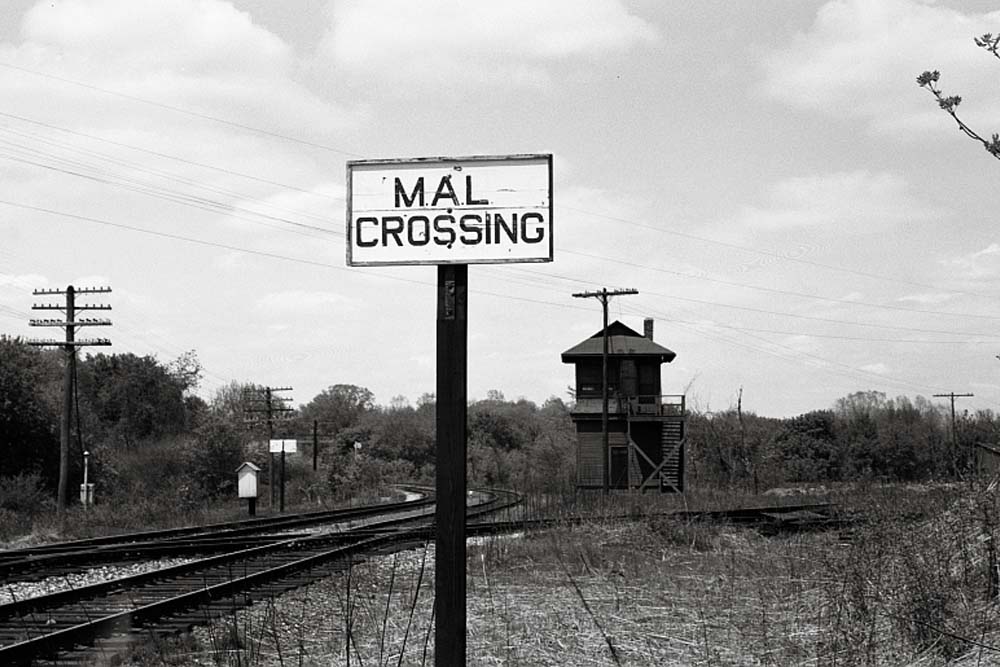

I suppose that straightening out a rail line like the one pictured would still require property lines to be redrawn and perhaps property owners to be compensated. If it doesn’t seem to matter with regard to maintaining speed or wearing out equipment and track, then I suppose it is a hassle best not attempted. Recent articles in Trains about today’s longer trains and placement of empty, short, or cars with EOC devices might require taking another look at re-aligning curves.